News

The Necessary Work of Developing AP African American Studies

Members of the development committee share what it took to create the course framework, how the “noise” around it impacted the effort, and their “long-term relationship of academic guardianship”

Whenever Antoinette Dempsey-Waters, Dr. Teresa Reed, and the nine other members of the Advanced Placement African American Studies development committee got together—be it on Zoom or in real life, in large groups or small—they had one common purpose: to create a framework that would do right by the students who take the course.

Internal disagreements over what should be included? Grappling with increased volume about and scrutiny of their work? Confusion over one point or another? They always returned to their North Star.

“We were doing something and creating something that had not been done or created before,” Dempsey-Waters tells The Elective. “Having one voice throughout this whole thing required everybody to put their egos aside and focus on what we were all doing. This is for the children, and we’re really trying to move forward with that.”

And despite a sometimes-bumpy road, they have done just that. AP African American Studies is currently in the second year of its pilot. More than 15,000 students in 40 states have taken it since 2022; hundreds of teachers have taught it. The course framework they use was released in February. The latest version will be made public in early December, and that is what will guide the course when it becomes operational nationally in the 2024-25 school year.

That milestone will represent the culmination—but not the conclusion—of the 11-person development committee’s work.

Dempsey-Waters, a high school teacher from Virginia, is a committee member in part because she created an African American Studies course in 2017. Then, in 2019, she was part of a committee to develop a statewide version for 16 districts as a virtual elective. Reed, another member, is a longtime university educator and dean of the University of Louisville’s School of Music and the chief reader for the course, responsible for overseeing the scoring process for AP Exams. She also has a relationship with AP going back nearly 20 years, from writing content modules for the Pre-AP Arts curriculum to serving as chief reader for AP Music Theory and helping develop AP Capstone.

Other committee members include Dr. Tiffany E. Barber, Assistant Professor of African American Art at the University of California-Los Angeles; David G. Embrick, Associate Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut; Dr. Robert J. Patterson, a professor of African American Studies at Georgetown University; Walter C. Rucker; Director of Graduate Studies and professor of African American Studies at Emory University; and high school educators Maurice Cowley, Patrice Francis, Kamasi Hill, Lisa Beth Hill, and Nelva Q. Williamson.

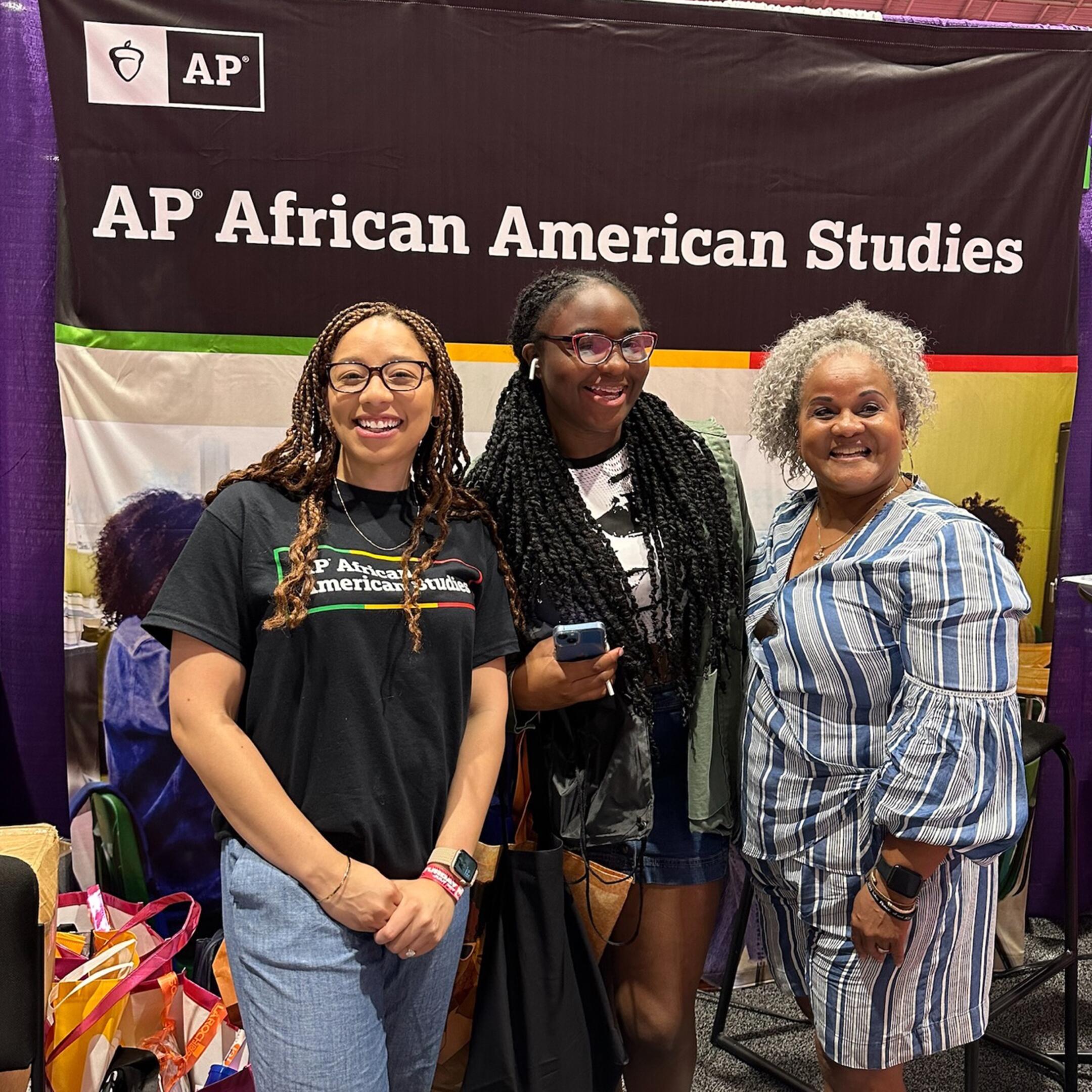

courtesy Antoinette Dempsey-Waters, University of Louisville

Antoinette Dempsey-Waters, left, and Dr. Teresa Reed, two members of the 11-person AP African American Studies development committee.

This unique group of six high school teachers and five higher education professors represent an interdisciplinary range of expertise: art, sociology, music, history. That is crucial to developing something as interdisciplinary as AP African American Studies—and delivering on the promise to students.

“It’s really about telling an honest and well-rounded version of the American story,” Reed says. “Kids need and deserve to engage with that story, not just in a way that fills their brains with facts and figures, but in a way that develops the skills that will support their ongoing curiosity for the rest of their lives.”

Developing the Course

The discipline of African American Studies threads together everything from history to music and art to politics into a broader narrative about the African American experience, past, present, and future. It began at San Francisco State College in 1968, and students can spend their entire academic careers—indeed, their entire professional lives—devoted to the field.

AP African American Studies is the first attempt at bringing a college-level course in the subject to high school students. The course framework covers a range of topics and required areas of study: early African kingdoms, the transatlantic slave trade, the Great Migration, the civil rights and “Black Is Beautiful” movements.

What’s not included in the core framework is accessible to teachers and students via the digital AP Classroom portal. “There’s never going to be enough time to teach everything that everyone thinks is important,” Reed acknowledges. “For the content that cannot be delivered in a given time frame, you deliver skills. And that’s the other component of what AP African American Studies does.”

Course creation began with exploratory discussions in spring and summer 2021. Dempsey-Waters was part of those, then in December she and five other educators, including Reed, began a more focused conversation about building an AP course. This initial development committee eventually grew to 11 members.

To write and structure the course framework, the committee consulted more than 300 African American Studies professors from more than 200 colleges. They collected and reviewed syllabi, comparing and contrasting what they included, what overlapped, what was unique. They considered feedback about what was required knowledge for an intro to African American Studies class, as well as what could actually be covered in a semester.

“This was a very open dialogue,” Dempsey-Waters says. “We all discussed what a college course required, as well as what was feasible for a high school student and teacher to learn and teach.”

No group of 11 people is monolithic, and disagreements and debate would arise within the committee. But when they did, members returned to their North Star: What do students need who take this course? And in the end, the higher ed members deferred to the high school educators about what was realistic. They would be the ones who had to teach the course, after all.

“It’s so much fun” working with the professors on the committee, Dempsey-Waters says. “They always want our opinion about how this actually looks in reality, how are teachers going to develop materials. It is an amazing dynamic.”

Marion S. Trikosko/Library of Congress

A crowd of marchers carry signs during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963. The civil rights movement is part of the essential elements included in Unit 4 of the AP African American Studies course framework.

The initial development process ended in December 2022. The result, released officially on February 1, was a course framework as rigorous as it is ambitious.

“This is not a course that's just for African American students and it's not an alternative to U.S. History,” says Nelva Q. Williamson, a high school teacher and member of the committee. “It is adding to the history of this country. It's bringing that kind of hidden history up to the forefront, and it should be available to all students.”

The Signal Lost in the "Noise"

But what should have been a capstone moment was met with a flurry of headlines, controversy, accusation, and misunderstanding.

Months earlier, a draft framework leaked to various media outlets. The released version included material differences that some argued too closely tracked aspects the state education leaders in Florida very vocally opposed. Members of the political right and left were both outraged, for different reasons, by the framework, which begat cycles of protests, recriminations, and zero-sum ultimatums.

(Recounting the whole gnarled, overheated narrative is impossible here. But Vox has a good primer, EdWeek has a timeline, and you can find College Board’s responses to it on the All Access members blog.)

Claims of political pressure have been unequivocally denied by College Board and the development committee. At the time, Reed told NPR that “there was an assumption that the leaked draft was somehow an official pronouncement of what the course would include or exclude. And then the released version … is to be compared to that.”

Nearly a year later, she says the committee found itself “waking up in a boxing ring without gloves. The development committee just wanted to create a great course for students.”

Dempsey-Waters adds that she “always knew what this course was about; everything else was just noise. And I was never going to be deterred or distracted by the noise.”

When she could, Dempsey-Waters tried to improve the conversation. “People would call me and ask, how can I do this?” she remembers. “And I would say, ‘Have you even read [the framework]?’ They would say, ‘No,’ and I would tell them, ‘Do me a favor: before we even talk, read it.’ And once people did, they’d come back and say, ‘It’s so amazing.’”

Dante A. Ciampaglia

A portion of the AP African American Studies course framework, focused on ancestral and ancient African societies.

Reed, too, did her part to better the discourse by helping people understand the particulars of developing an Advanced Placement course—particulars people like Reed take for granted but are often mysteries to the wider world. That meant stepping back from the jargon and explaining the differences between “framework” and “course.”

“Most folks don’t know what a framework is,” Reed says. “Assuming that the framework was synonymous with the course or was the same thing as a syllabus was completely inaccurate.”

It was an understandable mix-up. Most people never encounter a course framework; Reed never saw one before working with the AP. But so many people treated the framework as the course and ran with it that the result was confusion, misunderstanding, and judgment—not just in February, but whenever AP African American Studies was mentioned.

So, to clarify: The framework is the framework. “It is the essential, non-negotiable core of the knowledge and skills that the AP African American Studies course should impart,” Reed says. “Teachers then take the framework as their bible for developing their own course. It’s the starting point for personalizing or customizing the course experience to their school, their students, and their own specialization.”

This distinction is vital to understanding what the course is and can be, how it was built, and to understanding its future. Publishing a framework doesn’t represent the end of an AP course’s development. It’s just a step in an ongoing process that continues indefinitely.

“There’s a built-in system of quality control that requires, every few years, a refresh of the course and exam description, maybe another look at the framework, whatever it might be,” Reed says. “It’s part of what every AP course goes through.”

Indeed, the course framework has gone through another update, which will be released in early December. And whatever the response, this time the committee will be ready.

“I think from the time the course goes operational, and for the years that it’s available, there will always be people with opinions. You just have to keep it moving,” Reed says. “I’m certainly no less resolute than I was when I started. If anything, I’m more determined to see that this course launches and flourishes.”

Perseverance, Not Persecution

Still, Reed and Dempsey-Waters acknowledge challenges lay ahead. The biggest will be students confronting and critiquing facts that upend their prior knowledge—of America’s past, as well as its present.

“Because the African American lens and story have been so largely absent from the telling of the American story, that critique will quite naturally run into some cognitive dissonance,” Reed says. “That creates some discomfort, which is understandable. It creates some friction, not just for White students but for Black students, too, who in many ways get from our culture lessons about inferiority, absence, and stereotypes that are untrue.”

Challenging those assumptions was fundamental in developing AP African American Studies. It was very intentionally framed not around the negative view but the positive. “This is a perseverance story, not a persecution story,” Dempsey-Waters says.

“We have a few themes in AP AfAm, but that is really the thread that we as development committee members followed,” she adds. “When student’s leave this course, they’re going to leave it thinking, ‘Wow, the perseverance in spite of is amazing.’ That beautiful, gorgeous story of perseverance is everywhere.”

It’s a story students in the course pilot have clearly connected with.

“Learning and getting to know this stuff is very empowering. We get to know more about ourselves and we can celebrate ourselves in a much more different way other than just celebrating the fact that we got out slavery,” Ava H., from Houston, says. “There's so much to celebrate, and this class serves as the base for that.”

“It's cool to have someone in history who looks like you, like, just killing it,” agrees student Kahlila B., from Baton Rouge who took the course in the first year of the pilot. “Making strides legislatively, socially. It's cool to discuss the cultural aspects, too. We talk about the Black church—it's like our cultural experience is being validated.”

Reactions like those make everything—the work, the noise, the challenge—worth it for Reed and Dempsey-Waters. Both say the most rewarding experiences have been seeing students rise to the challenge of the course: culturally, socially, and academically.

“The first grading in Reston, seeing the student responses from a test on a framework that you were a part of writing, was insane,” Dempsey-Waters says. “It’s a culminating experience for the students, but it was also a culminating moment for me as a member of the development committee because it showed that they learned something.”

“Every single time I see a young kid who looks like I did when I was that age light up with curiosity and inspiration, I can’t tell you what that does to me,” Reed says. “Because I did not have that when I was at that age. It hits me in my core in a way that’s difficult to put into words. It affirms and reminds me that this is not just important work, this is not just great work—this is necessary work.”

And that work is never done. AP African American Studies is not, and never will be, frozen in time. And an active, engaged development committee is at the vanguard of the effort to ensure the course delivers on its promise to students—now and in the future.

“It’s a long-term relationship of academic guardianship and caretaking,” Reed says. “And it’s one that we are all grateful we got to do.”