News

Climate Change in the Classroom

In her new book, journalist Katie Worth investigates the challenges, conflicts, and opportunities of impacting how students learn about the environment

Earth Day is celebrated globally in ways big and small, from beach cleanups and tree plantings to letter-writing campaigns and climate change symposia. But the first Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, was more focused: a teach-in organized by educators and professors to bring attention to critical environmental issues and spur changes in how students encounter them.

A half-century later, with plenty of headlines about dire planetary status reports and pitched climate protests, It’s easy to forget that education and the environment have always orbited each other. And that America’s classrooms are still a stage for that conversation—and tension.

“One of the surprising things I found was how much friction there was over this issue,” investigative reporter Katie Worth tells The Elective. “We think of blue states and red states, but we’re all mostly purple states. We’re all purple communities, and this comes up in every school. People navigated it in a whole lot of ways.”

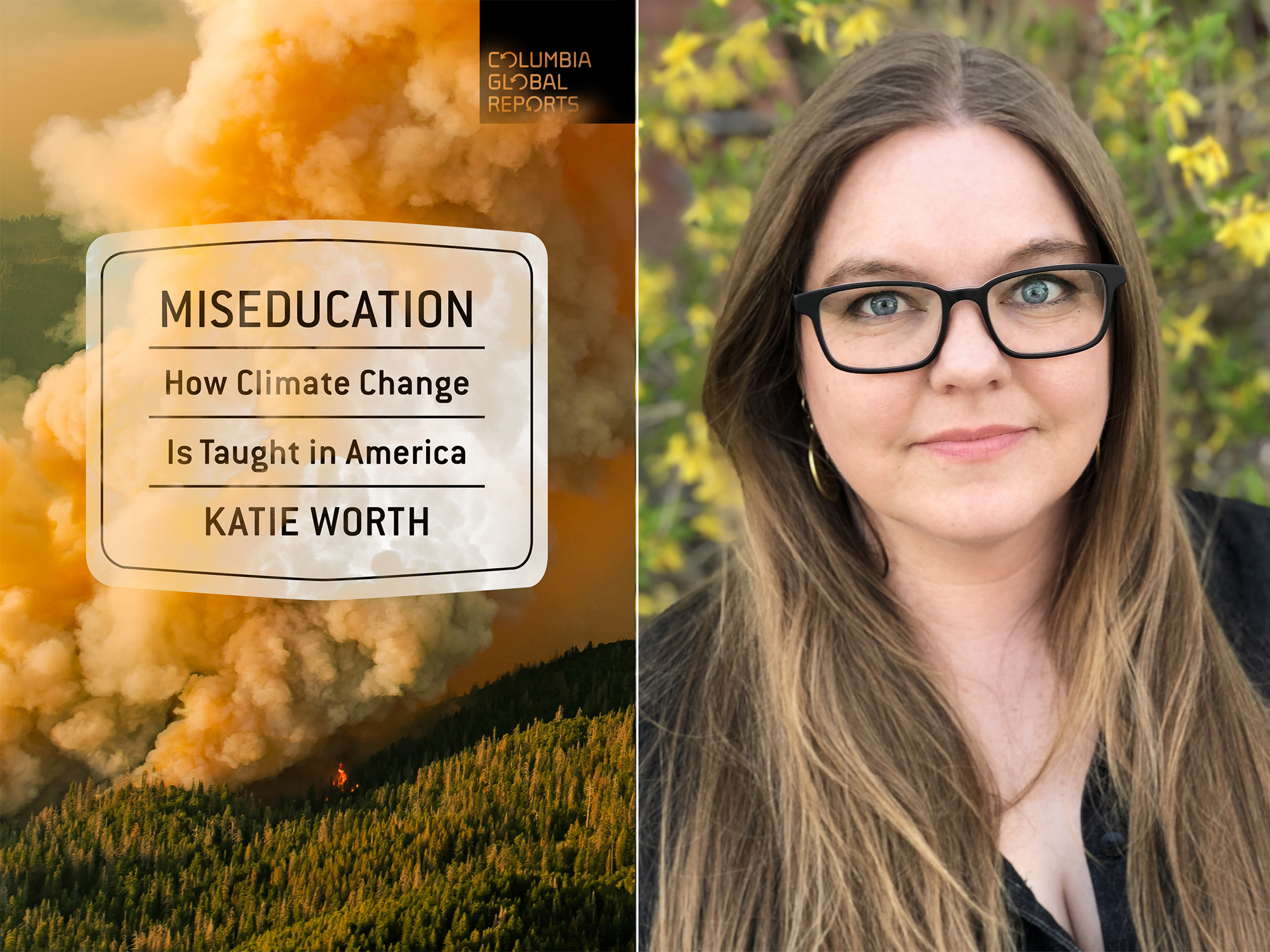

Worth made that discovery while writing Miseducation: How Climate Change is Taught in America, a snapshot of American climate education that explores cultural history, the development and various state implementations of the Next Generation Science Standards, and a diversity of classroom experiences. The slim but substantive book grew out of work she had done for PBS’ Frontline as well as reviews of textbooks and state policies and visits to more than a dozen communities.

Columbia Global Reports

She was also guided by climate data. “A study examining 12,000 peer-reviewed papers…published between 1991 and 2011 found 97 percent of those that expressed a position on the cause of climate change agreed that it was happening because of human activity,” Worth writes, adding that trying to find peer-reviewed research not linking humans with climate change is exceedingly difficult. “A review of global warming papers published in the first seven months of 2019 found zero.”

Worth allows a myriad of voices space to share their views, and none are presented judgmentally. Instead, she presents the results of her investigation factually and contextually to encourage critical engagement. And what emerges is a through line of inconsistency—in how states implement the NGSS, as well as the resources and materials available to teachers and students, even between classrooms in the same school.

Charles L. Nokes, an environmental science teacher in Arkansas, tells Worth he believes that carbon dioxide levels are rising, but he isn’t sold on the global impact of this situation. Sixth-grade teacher Kristen Del Real, at Worth’s old junior high school in Chico, California, spends the month of May on a greenhouse gas solutions project with her students. But a few years earlier Del Real discovered a history teacher down the hall “undermining her curriculum” by showing students climate-change-is-a-hoax videos on YouTube. Andrea C. Sampley, an AP Environmental Science teacher in Oklahoma City, took over the class from someone, she tells Worth, who said “they absolutely do not believe in climate change.”

Such divergent viewpoints, coupled with hyperpolarized politics, create a less than ideal learning environment. In the book, Worth highlights educators struggling to do right by their students, and students who are unmoored by the conflict between what they learn at school and what they hear at home. Teachers are authority figures; so are parents. How should a kid respond if their teacher organizes a lesson around a crisis their parents deem a hoax?

“What we know is that when kids learn about climate change, they care about it, and they do so more than their parents and their grandparents,” Worth says. “We also know that a quarter of American teenagers rejected the idea of a climate crisis. That’s a big chunk of students who are being misled about the fact that there is a crisis or are rejecting science that is conclusive on the issue. I think it’s probably really hard to navigate.”

golero/Getty Images

When teaching climate change, educators have found success connecting with students, who can often come to the topic hearing mixed messages, through self-discovery and solutions-oriented projects.

Miseducation documents that difficulty in places like California, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, and how it’s exacerbated by opportunistic special interests and confused, often overwhelmed communities trying to do right by their kids. But there’s another side to the story: educators—”not just in cities and college towns, but in the nation’s reddest states and also in the reddest parts of blue states”—creatively navigating often irreconcilable forces: directives from administrators, demands from parents, and obligations to students.

One route they’ve taken is solutions-focused projects, like ones created in AP Environmental Science and non-AP science classrooms alike. Those experiences benefit students academically. And, Worth says, “If you’re trying to encourage kids to think like scientists and engineers, getting them to work on a real problem is essential to giving them a good education about this.” But they’re also what students expect. “Right now, climate education is maybe 99 percent problem, 1 percent solution,” Frank Niepold says in the book. Niepold is Senior Climate Education Program Manager and Coordinator at National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. “Young people want 20 percent problem, 80 percent solution.”

The space for such instruction and investigation can be hard to find, especially when there’s an ideological divide between teacher and parent. But as Worth discovered, the more engaged educators made room for conversations, investigations, and solutions by sidestepping the conflict entirely—and empowering their students.

“Kids would parrot what they’ve heard an adult say, but also come up with their own legitimate questions,” Worth recalls. “And what I saw was teachers, in the best scenarios, treating those remarks with a lot of respect, acknowledging it can be really confusing when some people tell you one thing and others tell you another, then leaning on the science. They’d say, ‘I’m not here to tell you what to think. I’m not here to make you an activist. I’m just giving you the very best data that exists. We trust NASA; this is the data NASA gave us. We did our own experiment and looked at the history of temperature records all over the world. This is just data and you get to make your own decision about it.’”

“The kids in that moment may still defer to what the most important people in their lives say,” Worth adds. “But maybe there’s something planted, like, ‘Oh, I get to make my own decisions about it. This is science, this is the data, I can see it with my own eyes.’”

That isn’t just good climate education—it’s good education. Besides allowing students to engage with the climate crisis on their terms, these teachers are developing independent thinkers and, consequently, more engaged citizens. “Their work helps children understand the climate crisis unfolding around them,” Worth writes, “and prepares them to participate in civic deliberation over what to do next.”

Miseducation documents many cracks in American climate education while offering educators models for improving their engagement with students and communities. And in expanding the definition of “good climate education” to include students’ civic development, the book transmits a heightened sense of urgency.

At a moment when both the environment and democratic institutions seem in peril, giving students the tools to engage both with climate science and its societal implications is vital—not only to our nation’s future, but also to our planet’s.