Interview

Forgotten Pioneers of the Digital Revolution

After being nearly lost to time, six innovative women whose talent and genius ensured the success of ENIAC, the world’s first programmable digital computer, are restored to their central place in computing history in the book Proving Ground

Kathy Kleiman didn't set out to call attention to some of the most crucial experiences in computer science history. But as a college student studying computing, a question tugged at her: Where were all the women?

Kleiman's first experience programming computers came in junior high, when she joined Explorer Post, a coed branch of the Boy Scouts dedicated to Career Exploration. (Today, it's known simply as Exploring.) When she got to college, her early computing classes were nearly 50-50 men-women. But when she enrolled in more advanced courses, there were fewer and fewer women—sometimes one other, sometimes she was the only one.

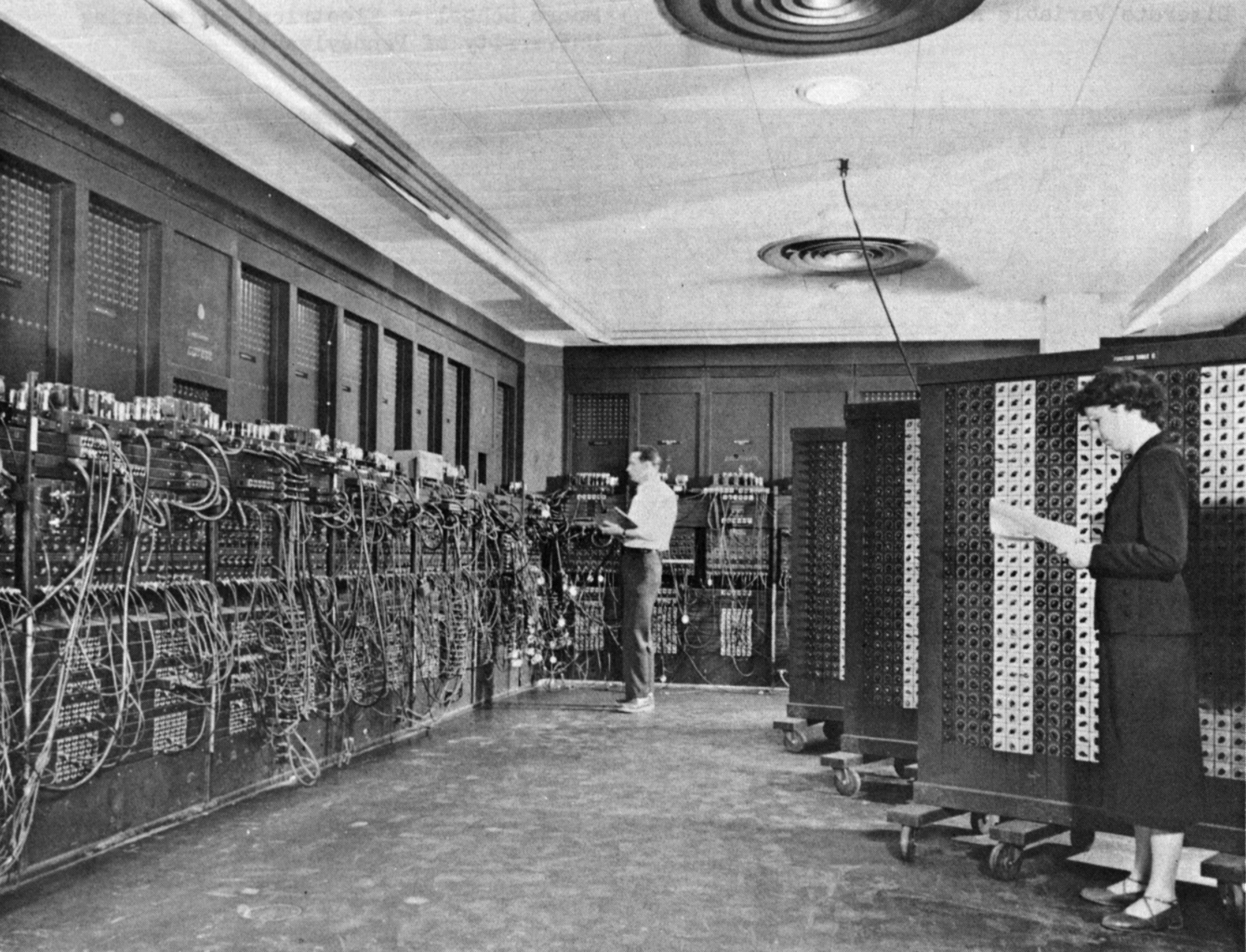

She needed to know why, so she looked to the past. When she did, she found, well, basically nothing. No legacies. No records. No names. Among the only photographic evidence Kleiman could find were black-and-white shots of anonymous women assuming work poses next to the hulking Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, or ENIAC, the world’s first programmable, electronic, digital computer, which debuted in early 1946. It was a start. But when she took the images to the Computer History Museum, in San Francisco, the director—a woman—dismissed the figures as "Refrigerator Ladies," models hired to pose with the ENIAC to sell it to the public the way someone would a home appliance.

The answer didn't satisfy Kleiman. For one, the women in the photos looked confident, assured, comfortable in the presence of the world's first supercomputer and, more, lugging the heavy wires and manipulating the countless dials and punch cards necessary to operate the ENIAC. Eventually her persistence paid off. She knew the names of the women in the photo. She also unearthed a legacy as brilliant as it was forgotten, which she preserves in her book Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World's First Modern Computer, out in paperback on July 26.

Betty Holberton (née Snyder), Jean Bartik (née Jennings), Kathleen Mauchly (née McNulty), Ruth Teitelbaum (née Lichterman), Marlyn Meltzer (née Wescoff), and Frances Spence (née Bilas)—the ENIAC Six—began their careers as computers (back when the word applied to people, not machines) creating artillery tables for the Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) during World War II, working out of the University of Pennsylvania. They were so smart and skilled at the math and logic it took to execute the work that they were selected to work on ENIAC, which was taking form in secret on campus.

Male engineers were building the hardware; the women would create what we’d now call the software (at the time, essentially, series and tables of numbers and complex calculations) that would be fed into and ensure the operability of the computer when it was finally turned on. "In the process, the profession of modern programming was born," Kleiman writes. "The six women were the first professional programmers of a modern computer." They also established standards and practices that have become core to coding and computer science—direct programming, loops, IF-THEN commands, bench test, and "breaking the point"—and had roles in developing foundational coding languages Fortran and COBOL. But, as Claire L. Evans writes in her book Broad Band, the ENIAC Six helped "introduce the century to the machine that would come to define it, and nobody congratulated them." Indeed, very few even remembered their contributions.

That's impossible now thanks to Kleiman, a lawyer, internet policy leader, founding member of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), and university instructor. (She also made a 20-minute documentary about the women, The Computers: The Remarkable Story of the ENIAC Programmers.) But some are trying to continue marginalizing the ENIAC Six’s contributions to computer science, Kleiman says. And that’s where her conversation with The Elective begins, before turning toward getting more young women into CS and the lessons the ENIAC Six have for us today at the dawning of the AI Age.

Tim Coburn Photography (Kleiman), Grand Central Publishing (cover)

Computer science and technology is full of experiences no one knows or talks about, either because they’re forgotten or hidden or buried. It’s a history that feels more fractured than other disciplines. Stories swirl around and you have to catch them at the right point, and if you miss them they disappear for years or longer.

I think there's actually an active pushback in this area. There are people who feel their territory has been impinged and they spend a lot of time pushing back on these stories, which I find very odd. As a lawyer, we had the glass ceiling. When I was a young lawyer, there weren't very many women partners. But eventually the women broke through. We were even allowed to have families, it was incredible; that never existed when I was a kid. And when it happened no one ever said women weren't there and didn't fight all the way through and weren't active in the industry. Whatever history was established continued to be told. Ditto for medicine.

But in computer science, there's always a cycle of, they didn't do it. “Women and Blacks couldn't have done anything important. We told you that 70 years ago, we told you that 50 years ago, we told you that 20 years ago, and we're telling you that again.” There's a book called The Computer Boys Take Over, and it's all about, “No, no, no, women in computing were just glorified clerical workers. Don't worry your pretty little heads about these stories.” I'm like, you're going to put a white man on the cover of this book and put it in the bookstore of the Computer History Museum, and now you want to encourage girls and minorities to go into computer science? You must be insane.

You bring this up at the end of your book. How are we still at this point, particularly with the wealth of first-person histories and oral histories and documentaries like yours? It seems to me that this is oddly foundational to tech history. There’s a cycle I found reading Claire L. Evans’ book Broad Band, Clive Thompson’s book Coders, and now yours: Women get into programming because no one else wants to do it, they establish and build important infrastructure, programming becomes prestigious, men push them out. Then, 20 years later, the cycle repeats. At some point you’d think this cycle would break, yet it perpetuates and here we are talking about it in 2023. Why do you think that is? Is it a feature, not a bug, of the industry?

I lived through this period, starting in the early '80s. So forgive me if I don't think women got pushed out. And that's where I think this starts.

When I want to look like a lawyer, I suit up. If you see me in a full-blue suit, you know I'm prepared for battle. I do international internet policy; I do public interest law. So if I'm suited up, it means I'm going to war with the big brands. But at a Computer History Museum event, just as covid was lifting, Thomas Haigh womanned-up. He had Maria Klawe on one side and [journalist] Katie Hafner on the other side. And he had them repeating these myths about early women in computing. But then he got to his new thing, that women in the 1960s and '70s did nothing more important than data processing. Maria Klawe, president of Harvey Mudd University, nearly took his head off. "What are you talking about?! Everyone that I know was active. Women were doing magnificent things in the '60s and '70s in computing. How can you even say that?" I'm paraphrasing, of course. And he retreated just a little bit, only to repeat it later.*

I've got a really close friend who wrote a pamphlet called My Second Computer was a UNIVAC I. He goes back through the '50s and '60s, and he always starts his stories with, "All of my managers were women." So I think what happened is, there were a huge amount of openings and the men came in because they were better positioned. If you're going to expand the field by 90%, you can fill it with lots of men. And somehow, for whatever reason, they want to perpetuate the myth that they forced the women out. But Fran Allen was there, and Thelma Estrin was there, and Maria Klawe was there, and Barbara Simons was there, and it goes on and on and on. I know women who have been involved a long time. And that's where we're finding these stories. They didn't go away in the '60s, '70s, and '80s. They trained everybody else and they were the role models.

I guess what I meant by “pushing out” was from the official narrative. Like you get into in the book, the ENIAC Six are working at a time when women are in the workforce because of World War II. When men come back, they push women out—but not the ENIAC Six. Their jobs are secure because they are the undeniable, undisputed experts in this area. These women made amazing breakthroughs, they laid the groundwork for even more. But then the narrative retrenches back to the real geniuses being the guys in the garage or the pointy-headed Ivy League brainiacs imagining the future. The women who created the foundation for modern programming barely rate as footnotes.

They pushed the women out of the story, but my sense is that they're also implying that the women got pushed out of the field and the men took over. And that's the myth I'm shadowboxing now. Women never left, and they continue to be leaders. Percentage-wise, they probably went down because numbers-wise jobs went up.

But, I agree with you. I learned about the home front in World War II in high school, but I learned that women went to the factories. Women and children, after school, were sent to the farms because no one was picking. It wasn't until I started doing all this research that I realized, in STEM during World War II, there were 20–25 jobs per woman. That's what the statistics they were compiling internally said. Young women didn't know that at the time. But there was this huge need, which reminds me of today.

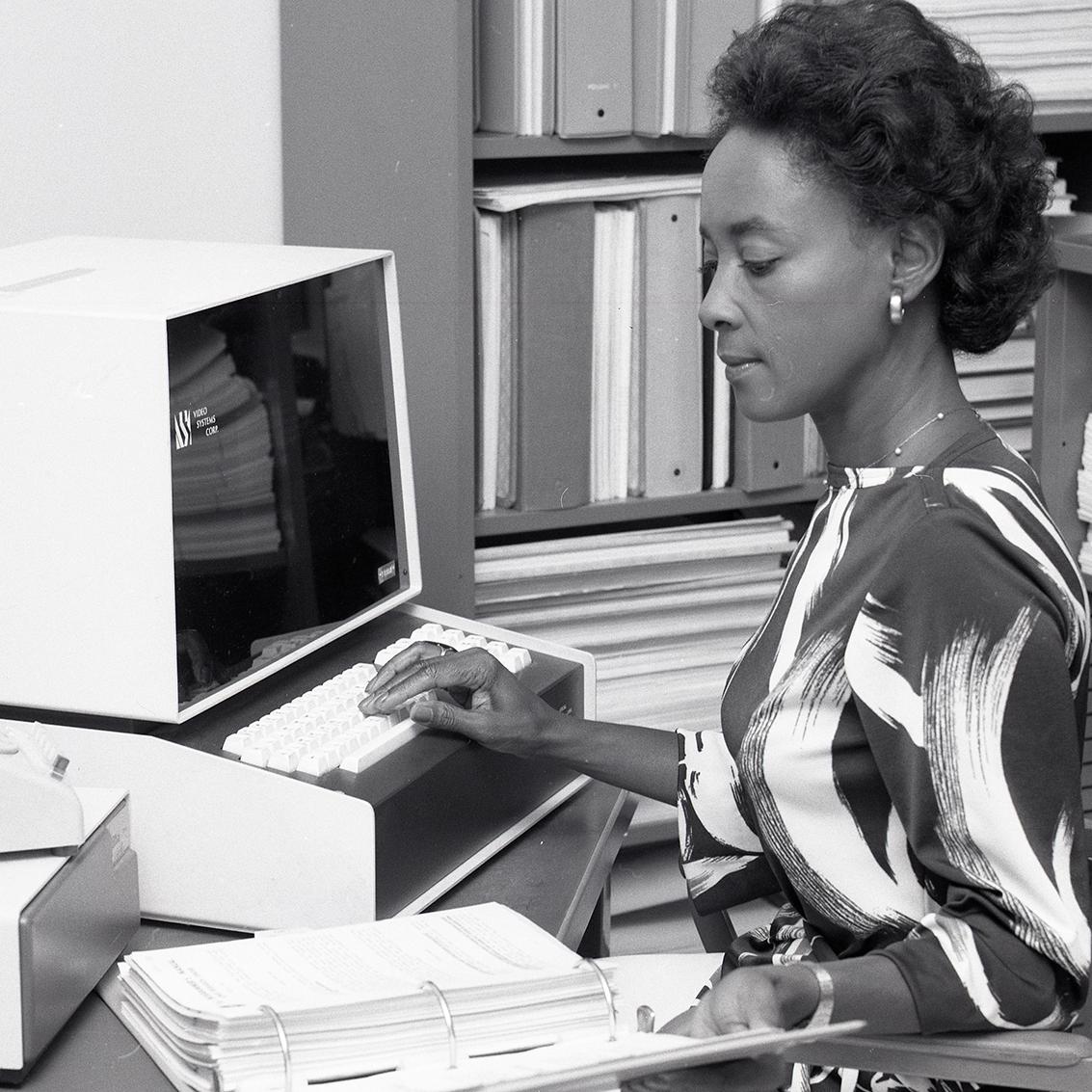

U.S. Army

Betty Snyder (foreground) and Glenn A. Beck (background) program ENIAC in Ballistics Research Laboratory Building 328.

In the absence of a collective mobilization effort, like a world war, how does the nation get across to young women that not only is there a need for them but there is a place for them in this industry?

There are 740,000 openings in cyber right now. That's what the dean of the college of cyber at the NSA told the Jean Bartik Computing Symposium in February. All four military academies are desperately trying to recruit women and minority computer science and cyber cadets and mobilize the best of everyone to go into cyber and go into computer science. And not just the military academies, but every place else, from what I can gather.

I guess it comes back to the same question: Why am I walking into rooms in 2023 and getting nods of recognition when I tell the story of walking into my C class when I was in college and sitting next to the only other woman in this room of 60 people? Back then, once you got to the upper-level computer science courses maybe there was one other woman; maybe you were the only one. But I was at the Computer History Museum for IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers] last month, and I said, "Has anyone else had the same experience?" And every woman in the room, it looked like, raised their hand.

Earlier, I was at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and I told that story. The next day I was brought over to the new media center, and a woman who wasn't even in my lecture told exactly the same story of walking into her computer science class recently and sitting next to the only other woman in the room. What's going on?

How pervasive is this viewpoint you’re “shadowboxing” when it comes to women’s role in the development of computer science? Is it a minority opinion that just gets more attention than it should? Or is it worse than that?

I think they're getting much more attention than they should. But I also don't think that's the mainstream story. My day-to-day job is internet policy, so I walk into rooms that are mostly all men and I sit down and work on internet policy. When I'm not doing that, I train both men and women to do this and try to particularly encourage women to enter the field. We know from, say, Congress, that when women come into a room the issues and policies become a little different. Maybe education becomes more central, or child welfare. You bring women from around the world into an internet policy discussion, I promise you things change a little bit.

So that’s my focus in teaching. I teach internet technology and governance for lawyers to third-year law students. I tell them they can come in with no technical background, but I promise them they're going to get technical background and they have to be ready for that. We're not allowed to talk about law or policy for five weeks, as we go through the layers of the internet. They look at me like I’m crazy. But they learn about ARPANET and data packets, the mnemonic for IP addresses (which is domain names), they talk to technologists because that’s key—these guys have to know how to work with technologists. So my job is just figuring out ways to… I try not to spend most of my energy fighting the people who are out there. I wrote what I think is a really positive and inclusive story, and then my job is to bring as many people into the room as possible. That’s what creates the new future.

Speaking of the future, we’re talking as much consternation grips the world about AI. You write about how some in the press at the time ENIAC debuted—including a very-of-its-time newsreel clip—talked about the computer as an “electronic brain” and how some of the women bristled at that interpretation. You have a quote from Jean where she says, “The ENIAC wasn’t a brain in any sense. It cannot reason, as computers still cannot reason, but it could give people more data in reasoning...” It reminds me of how people talk about AI: Is it thinking? It is not thinking? Can it think? What lessons do the ENIAC Six have for our current technologies—and the people working on them?

This is my personal view of the world overlaid on their personal view of the world. When I did my right turn into academia a few years ago, I went to Princeton as a visiting scholar. I was at the Center for Information Technology Policy, where we had lawyers and behavioral scientists and ethicists working with PhD computer scientists on questions about the implications of their work. One of the questions I asked about AI machine learning was, “How do I know? How do I know how the decision was made? So, as a lawyer, how can I appeal it?” The basis of an appeal is to question the reasoning of something and to show that it was based on such-and-such and such-and-such. If a computer denies me benefits for welfare or turns down my parole, how can I appeal? The students looked at me and said, “You can’t. We don’t know how it reasons.” And I said, “How do I know if it’s consistent?” And they said, “It won’t be. It will learn something in the next nanosecond and it could change its decision on the same basic underlying facts.” And I said, “This is not useful, guys.”

US Army Research Laboratory Archive

Gloria Ruth Gordon (Bolotsky) and Esther Gerston at work on the ENIAC.

One of the things about the ENIAC programmers—and it's part of this book but also my next book, about the creation of UNIVAC, the successor to ENIAC—is that they cared very much how people used their technology, Betty Holberton and Jean Bartik in particular, who would go on to careers in this area. Betty created the first sort merge. She sat down with a deck of cards and worked on a sorting routine because she thought that data was the big problem for potential clients—Prudential Insurance, Nielsen Surveys, the U.S. Census Bureau, all who would be original purchasers of the UNIVAC 1—and she wanted to give them the tools for using it. She would go on to create the C10, which was the instruction code of the UNIVAC 1.

According to Milly Koss, who was on the software team of UNIVAC under Grace Hopper and who I knew at Harvard when she was VP of IT, said Betty Holberton's instruction code was so powerful and so mnemonic, so useful, that it delayed the creation of programming languages by several years. They didn't need it. And then Betty would go on and help lay the foundation of programming languages, along with Jean Sammet and Grace Hopper.

So it seems to me that the women were very concerned about who used this technology: How to make it accessible, how to make it usable, how to make it easier even though it wasn't easy. Maybe that's what scares people away, that they're trying to make it accessible.

You worked to document the lives, stories, and impact of the ENIAC Six for years, going back to college. How has their experience impacted your work, as a lawyer and in internet policy, and the way you see what you do and how you do it?

In addition to the day-to-day work of what I would call public interest internet law, which has to do with the multi-stakeholder model of ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the internet governance group, and the role of the Noncommercial Users Constituency, which I cofounded 20 years ago with Milton Mueller. That's kind of the day job. But with the ENIAC programmers, I now think of what I do as part of the K–20 pipeline.

We always hear about it as K–12, getting kids interested and getting them that head start in STEM in high school. You have to have an enormous amount of preparation, unfortunately, to go into college in these fields. That's not true of sociology or psychology. Nobody expects you to have high school sociology, but somehow they expect you to have high school computer science, which has helped eliminate girls for many years. So places like Harvey Mudd now have two tracks to start with, if you have experience and if you don't have experience. You'll meet up eventually, and that's how they've gotten closer to 50-50, or maybe they're already at 50-50.

But it's not just that. We have the college courses; we want those computer science majors. But I want the computer science grad students. I want the kids who do technology, whether computer science or not. I want students in the PhD programs looking at the policies. I work with the School of Communications at American University. We have an Internet Governance Lab that's very diverse with students and faculty from across the university. And then my courses, for upper-level law students—a lot of [master of laws students], a lot of students from other countries. They’re already lawyers in their countries, but they want to study American law and the specialization. They're taking my courses, too, and going back to their countries and, I can say happily, becoming part of internet policy groups there.

So the K–20 pipeline, and of course every student of mine, gets to hear that the first teams were both women and men, and that's been continuous all the way through, regardless of what the media says, and that ICANN was founded by women and men. And right now, for the first time in 20 years of ICANN history, we have a female chair of the board and a female interim acting president and CEO. We all argue in our group, but every woman there hugged each other when that happened. It was a glorious moment that made all of us shine.

So I just like to show that there's a continuous history. We belong here.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

*Note: The event Kleiman refers to here took place at the Computer History Museum in April 2022 and was focused on Klara Dán von Neumann (also known as Klári), “a computer programming pioneer who worked on the Monte Carlo simulations of atomic and thermonuclear explosions immediately after World War II,” per the museum, in part by learning “to operate the ENIAC” and then working with Nick Metropolis from Los Alamos to reconfigure ENIAC to translate husband John von Neumann’s mathematical treatments to code, debug it, and eventually set up the Monte Carlo simulations. Haigh, who “uncovered Klári’s outsize role,” called Klara Dán von Neumann, again, per the museum, “a ‘super-programmer,’ creating the first modern computer code ever executed. She was there at the very start of the discipline of computer programming, but her role in computing history was hidden.”

All of this is worth noting, first, to point out the event itself was centered on a forgotten woman of computing history. It wasn’t just Haigh holding court on how women don’t deserve a central role in the story of computing. (The full event is online.) And, second, Klara Dán von Neumann appears only once in Proving Ground, near the end, in relation to helping with Los Alamos calculations after the war. (Her role in the book is so brief she doesn’t have an index entry, likely because she’s not central to the story Kleiman is telling about the ENIAC Six.) John von Neumann, however, is a presence, as is his belief that ENIAC could be reengineered to store programs, not just numbers. At the Computer History Museum event, Haigh claimed Klara wrote the first modern code ever produced (to execute the nuclear simulations run on ENIAC at Los Alamos). That’s debatable, too, given the stories and history collected and shared by, among others, Kleiman and Claire L. Evans in Broad Band, as well as the oral history record (such as from the National Center for Women & Information Technology and the Women in Computing Oral History Collection).

This is just further evidence of the need for robust, diverse, good-faith inputs in telling the full history of computer science. And it’s a reminder that there’s far more at stake than anyone’s credentials or who wins the speaking gigs and prizes. An incomplete, skewed narrative of the foundation and development of computer science not only ensures toxic elements remain entrenched in the field, it actively feeds the industry’s representation problem. If women and people of color don’t see themselves reflected in the CS story—80 years ago, 50 years ago, 20 years ago, 10 months ago—why would they believe there’s a place for them in it today? There is room in the computing world for men and women, existing side by side, in the creation of technology. Indeed, the record shows a robust, fruitful legacy of such collaboration. One has not, does not, and cannot negate the other—whether that’s building hardware, writing code, or researching history.