In Our Feeds

Everybody Into the Polls! Eight Experiences That Made Us Smarter—and Better—Citizens

A special democracy-in-action edition of our weekly Smarter column to celebrate Independence Day

It’s the nation’s 246th birthday, and we feel like celebrating. So we’re doing something a little different for this week’s Five Things That Made Us Smarter. Rather than making sense of the deluge of content flooding our feeds, we’re sharing our first (or most impactful) experiences with voting and civic engagement. There’s no greater right than the right to vote. It’s what makes this land your land and my land and our land. The moments we’re sharing this week are bedrock to who we are as people and citizens. They’re also crucial reminders that the foundations of good citizenship begin, for most people, at home and at a young age—and that the foundations of good citizenship never include recriminations, purity tests, or echo chambers. It’s a reality we all need to be reminded of from time to time, especially these days, as we navigate the unpredictable and imperfect purple mountain majesty we call America.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

New Yorkers wait at the polling station as they register their votes in the 1964 presidential election in New York, November 5, 1964. A lot has changed since then, but not the excitement and hubbub in polling stations as people exercise their franchise.

Pull of the Polls

For as long as I can remember, I clamored to do grown-up things. Being a child was so boring and, well, childish. And to elementary school me, there was nothing as cool and grown-up as voting. I begged Mom to take me with her to polls. She relented that first time—and then just about every time I asked afterwards—and we drove to John J. Pershing Elementary School. We saw the signs along the sidewalk, the last handshakes of political hopefuls, the excited civic chatter in line. When we got into the school, there were these mysterious booths with short curtains that, when you entered, closed with a “shwoosh!” And there were buttons that clicked as you made your choices. Standing with Mom, I was too short see who she was voting for—but it all seemed so important, so grown up. She made her choices carefully. That was 1972.

I closed the curtain myself on November 6, 1984. That would have been my sophomore year in college, but I had dropped out and was answering phones in an office, reading Stephen King novels all day, and wondering what to do with my life. My launch to adulthood was stalled. But it was “Morning in America.” And on that sunny November day, I took time off from my dead-end job, put on church clothes—pumps and hose—and drove to my polling place not far from John J. Pershing. I got in line, chatted about President Reagan with the other adults, and shook hands with the state rep candidate. I approached the booth with the curtain, stepped in, pulled the handle—“swoosh!” Then I carefully clicked the buttons of democracy. Outside that booth, I may have been struggling in school to find my way, but for those few moments behind the curtain I was a citizen, all grown up. —Stefanie Sanford

Thrill of the Vote

As one of the oldest students in my high school senior class (thanks to an October birthday), I was one of the first of my peers to turn 18 and experience voting. It was Fall 1997, and despite a serious case of senioritis I was thrilled at the prospect of casting my vote in local elections. Although I was a bit disappointed that my designated polling location was in my high school’s commons and not somewhere new, exciting, and more “adult,” there was something quaint and familiar about it.

I remember dressing up for school on Election Day (the day I still prefer to cast my vote) and making my mom take a picture for posterity. (Sadly, no one has been able to locate this photo.) I also took a journal with me that day that contained notes I had jotted down indicating who I was most compelled to vote for and why. I recall feeling I had done my homework after consulting the League of Women’s Voters brochure I had received in the mail a few weeks earlier.

Because this was the late 1990s, my voting booth included a privacy curtain (that I closed with the dramatic flair that only a high school drama student can pull off) and a punch-style voting machine. Although I had been encouraged to vote straight ticket by my dad to “save time” (!), I methodically clicked through each race, checking against my notes, as I made my way through the ballot. The experience was exhilarating.

Needless to say, I was flying high on adrenaline during the 1999 primary and general elections when I got to cast my vote in my first gubernatorial and congressional races. At that point, I was an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin and voted in the then un-airconditioned Gregory Gymnasium. Despite the heat and humidity, (yes, even in the spring and fall), I took great pride in fulfilling my civic duty. I was also excited to vote for George W. Bush for governor and Carole Keeton Rylander for Texas railroad commissioner, both of whom I had met in the summer of 1997 while attending Texas Girls State.

Looking back, I am delightfully surprised by some of the choices I made on those election days and how those choices would later impact my life. For example, in 1999, I voted for Craig Enoch for Texas Supreme Court Justice, who handily won his election that year. My husband, John, clerked for Justice Enoch at the Texas Supreme Court from 1999-2000, and in 2006 Justice Enoch married John and me in a legal ceremony in advance of our destination wedding in Mexico. Coincidence? Perhaps. But I like to think this type of evidence confirms the notion that your vote always matters. —Michelle Cruz Arnold

Sara D. Davis/Getty Images

Kids Vote polling attendants Aiden Cushman (left) and Melton Henry, both 11, monitor the Kids Vote polling booths at E.K. Powe Elementary School on November 8, 2016, in Durham, North Carolina.

Read My Lips—No. New. Homework.

The first time I voted, I was 7 years old. And before anyone starts shouting “voter fraud!” and reporting my toddler-felony to the Board of Elections, know that it was part of a school-wide civics project where every student at Powell Elementary cast a mock ballot in the 1992 presidential contest. They were tallied by classroom, then by grade, with whole-school results reported at the end of the day. I assume a sharp political analyst could have detected political fault lines between striving kindergarteners and patrician fifth graders. I don’t remember much in the way of analysis, just color-coded boards on the outside of each classroom, the pre-internet analogue to the red/blue maps that now dominate our political discourse, on Election Day and everyday.

What I do vividly remember from that election, featuring the incumbent George H.W. Bush against a saxophone-playing southern democrat named Bill Clinton, is that I got sent to the principal’s office for coming into class with a “Vote for Bush!” placard draped around my neck. There wasn’t much in the way of candidate advocacy among the first-graders, and I quickly learned that campaigning in a polling place—even if it happens to be your homeroom—is frowned upon. The reasons I favored Bush the Elder are lost to time (I assume it had something to do with winning the first Gulf War, since that involved a lot of jet planes and I was very much into those), but my view proved persuasive. In a sea of Clinton red, my little classroom was a lone island of Bush-hued blue, proving that campaign advertising actually works—at least among people with a first-grade reading level. —Eric Johnson

Bilateral Bias

I grew up in Canada and cast my first vote for prime minister in 1988. I loved learning about the candidates for the Member of Parliament seat in our riding (or electoral district) and adding the layer of who I wanted to be PM. I voted that year for Jag Bhaduria in our riding, mainly because I wanted Liberal Party candidate and former PM John Turner, a bright and progressive leader, to win. He was running against Brian Mulroney of the Progressive Conservatives, who was vying for his second term. Interesting note about Turner—he only served in office for 79 days. He inherited the reins from Pierre Trudeau, father of current leader Justin Trudeau, who resigned in 1984 after more than 15 years in office. Pierre Trudeau said it was the appropriate time for someone else to assume the challenge and made the decision after a long walk in a blizzard. What could be more Canadian?

Mulroney prevailed, and one of the cornerstones of his time in office was the strong relationship he shared with President Ronald Reagan. They agreed on many issues, most significantly the North American Free Trade Agreement. But it was a meeting in Quebec City when the two leaders of Irish descent belted out “When Irish Eyes are Smiling” that solidified their bond.

The relationship between the two countries’ leaders has always fascinated me. I wrote a college paper about how the connection between the president and prime minister impacted policy. That association peaked with Mulroney and Reagan after a nadir with Prime Minister Diefenbaker and President Kennedy, who found the Canadian leader boring. Policy disputes defined their dealings—not singing.

Voting and politics are essential parts of my life. Plus, I met my American husband in a Canadian politics class, so the ties between the two countries and our politics have played a huge role for me. —Karen Lanning

Dante A. Ciampaglia

A selection of campaign and political buttons from the author's collection, including the Dukakis/Bentsen pin that his mom wore throughout the 1988 presidential campaign.

I Love the Sound of Democracy on Election Day

The first time I voted was the 2000 presidential primary. By the time we got to go to the polls in Pennsylvania, then-Vice President Al Gore already secured the Democratic nomination. So I cast my ballot for Bill Bradley, partly as a protest to this system where some states’ votes count more than others during primaries, partly as a protest against the presumptive nominee. It was kind of anticlimactic, but still—first time! Truthfully, though, it didn’t leave much of a mark on who I am as a citizen. I was always going to vote as soon as I was able because, in my house, we were raised to hold the right (and rite) to vote as sacred. My mom voted in every election, full stop. But she did more than hit the polling place on her way back from work. She would come home, get me, and we’d go to the polls together. Without question, one of the thrills of my young life was entering the voting booth with her. It was an up-close-and-personal encounter with democracy, and the poll workers, always elderly, loved that a kid was so into voting. But it was also a singular sensory experience. The reason voting in 2000 was kind of meh, besides the candidates, is that my first time in the booth spoiled me forever.

It was November 8, 1988, and my mom and I went to the public pool that served as our polling site. She had worn this “Steel Workers for Dukakis Bentsen 88” pin for months, so I knew how she’d vote. When we entered the booth, a poll worker explained how to cast a vote—it was one of those old, heavy-duty tank-like machines with levers and buttons—and she hit a switch that closed the discarded-dentist-office curtain with a tinkly rattle. I looked up at all the levers—so many candidates!—and my mom looked down at me. “Want to try?” Uh, yeah! She lifts me up—I was about to turn 7—and together we flipped down the lever for Michael Dukakis, which registered with a heavy “ka-chunk.” It was the most satisfying sound in the world. She put me down, made the rest of her choices, and lifted me up again to press the big red button that registered the votes. Another amazing sequence of sounds: a whirring of gears turning inside the machine, numerous chunk-kas of resetting levers, and the scrape of metal as the curtain pulled back. Absolutely mind melting. I carry that memory with me every time I vote. Those lever machines are extinct: Pennsylvania replaced them with touchscreens (lame), and now living in New York I vote by filling in a bubble sheet and feeding it into a computer (yawn.) But more importantly, that night in ’88 left me yearning to vote for real. And it imprinted on me something I knew abstractly from books and TV: that citizenship is a tactile thing. All of us have a voice and the right to use it, be it by joining a rally, speaking at a school board meeting, or simply ka-chunking a lever in a voting booth. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

A Thoroughly Jersey First Vote

My first job out of college, in the summer of 2004, was writing for the largest newspaper in Hudson County, New Jersey: The Jersey Journal. This was a big deal, since my family had been getting this paper delivered for the past 15 years, and it was my first window into learning about local elections. The highlight of that early relationship came on election day in November 1992, when I was 11. A political cartoon I did as a class assignment was published in the Journal, thanks to my grammar school teacher reaching out to the paper. Little did I know that this would only be the beginning of my work for the Journal.

Fast forward to May 25th 2004 when Glenn Cunningham, the mayor of the county’s largest city, Jersey City, died of a heart attack. Since I was both living and working in Jersey City at the time, the five-month campaign to elect a new mayor in the November special election became a big part of my everyday life. There were 11 main candidates all vying for the job, and the Journal covered them all to some extent. This gave me a unique opportunity to learn enough about each one to eventually cast a well-informed vote my first time utilizing that right. In a presidential election year, instead of focusing on George W. Bush running for re-election against John Kerry, it was fun to keep day-to-day track of a very competitive local race. After five months of journalistic research, my guy came in third. I wore my “I Voted” sticker for a week. ¡Viva democracy! —Christian Niedan

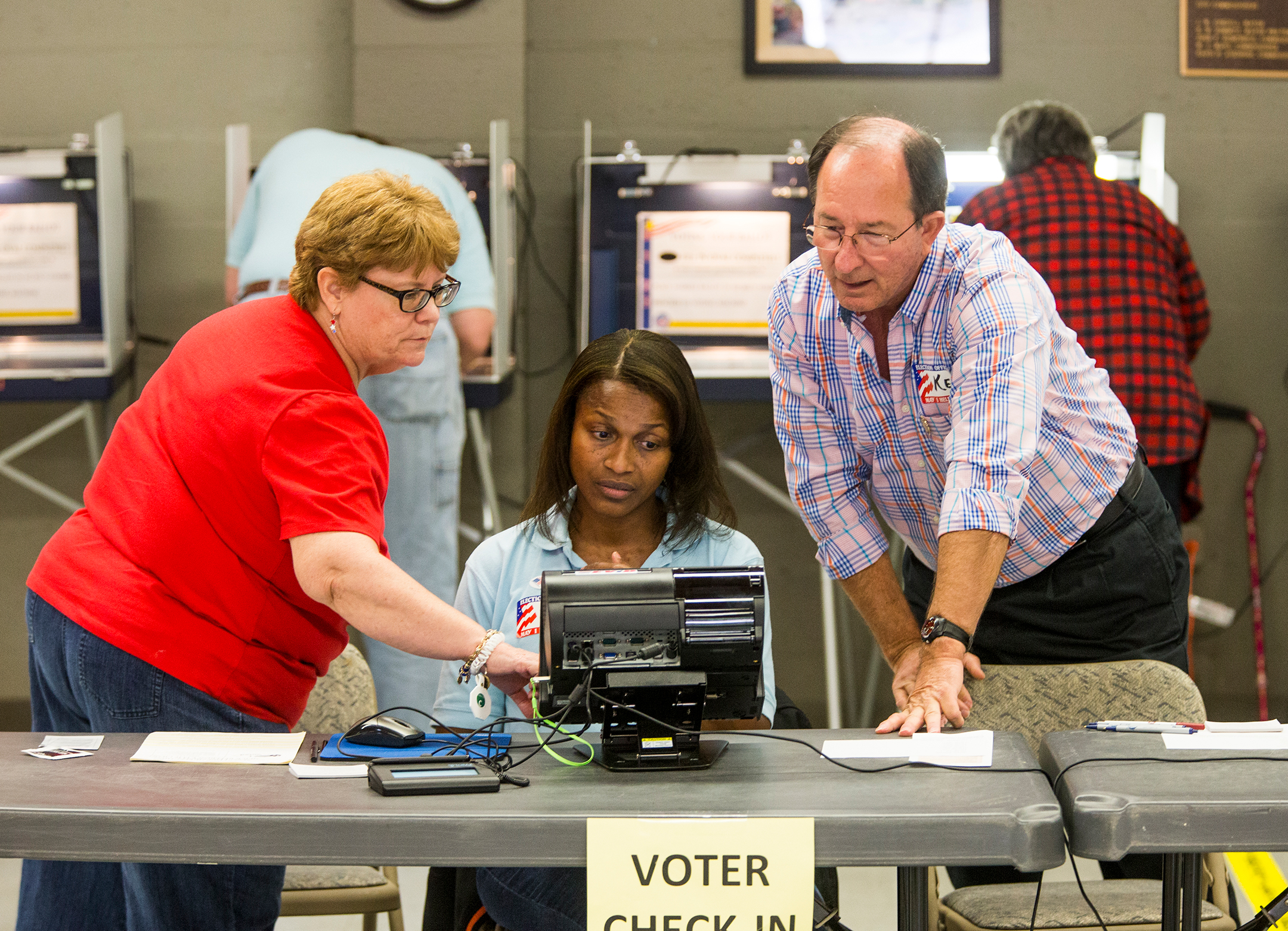

Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images

Poll workers, like these seen on November 8, 2016, from the Leon County Supervisor of Elections office in Tallahassee, Florida, are the secret glue holding elections together.

Electing to Serve on Election Day

I voted for the first time in 2012. I voted early, and I have to admit the experience was a little anticlimactic: no long lines, no fanfare—I'm not even sure I got a sticker. But that was alright. I had a job to do on Election Day. I had signed up to be a poll worker. So that morning, I woke up early and drove to a nearby elementary school where I met the people I would be spending the day with. I was the youngest by far. Looking back now, my fellow workers were probably only middle-aged, but to me, they were time-tested, grizzled experts who knew their way around a polling place. Two of them took me under their wing. For the rest of the day, we confirmed voters' registration statuses and that they were in the right place. We took the job seriously, ensuring that this important day for our democracy ran smoothly. And despite the election's political significance, I remember my fellow workers being decidedly close-mouthed about their own political beliefs. We didn't talk about whether we were Obama or Romney supporters; that wasn't the point. What was important was that we made sure everyone who showed up had a chance to have a say in our democracy.

It wasn't all smooth sailing. At the end of the night, we had to manually count all the ballots, ensuring the machines counting the votes hadn't missed anything. We dumped the ballots onto the ground and began to count. That's when I realized something was amiss. I noticed Senator Richard Lugar on several of the ballots, but he had been defeated in the primary earlier that year. We hypothesized that one of the machines hadn't been emptied after the primary. That changed our task from simply counting the ballots, to counting and identifying and removing old ones. Finally, after several hours, we were satisfied that we had an accurate number. One of the workers was assigned to deliver the ballots to our town hall. The rest of us could go home, satisfied that we had done our part to ensure the integrity of the election. —Hannah Van Drie

Hey Hey! Ho Ho! Organized Recess Has Got to Go!

Unlike my colleagues, I don’t remember my first time voting. Perhaps it was because I turned 18 in 1997 after a key presidential election year. But what I do remember is the first time I took civic action.

I was in fourth grade, and as a class we had just gotten in big trouble because we were misbehaving at recess. (To be very specific: There were kids climbing up the football goalposts despite repeated warnings, day after day, to stop.) The punishment? The school took away our right to free play during recess and instead made us play organized games. I don’t remember which, but I’m sure they were all sports—I was terrible at sports! I was also not one to just sit around and stew, so I took action. I started a petition to ban organized recess and restore free play, and circulated it at the end of fourth grade math, when we were supposed to be working on that day’s assignment. The teacher noticed, confiscated it, found out I was the organizer, and called me up to class to lecture me on how I was supposed to be focused on my assignment. To which I replied I had already finished my assignment. She claimed I replied in a “smart” tone and I was sent to the principal’s office for the first and only time.

Sitting outside the principal’s office, I rehearsed a speech in my head about how I was pretty sure I had a right to petition the school for a redress of grievances. But I never had to deliver it. I never actually had to see the principal. I did have to sit there and sweat about it for a good long while, though.

A short time after that almost-visit, organized recess ended and free play was restored. —Michele McNeil

Ariel Skelley/Getty Images

Program Announcement: College Board Launches Voter Registration Initiative

Before we go, we wanted to let our readers know about an excellent new initiative, that will launch on July 4, that will enable eligible students 18 years or older who participate in College Board programs to register to vote. From the press release: “The initiative builds on longstanding partnerships College Board has forged with leading nonpartisan civic education organizations, including the National Constitution Center and Institute for Citizens & Scholars. These efforts are designed to increase students’ knowledge, skills, and agency, and they complement the in-depth study of U.S. government by hundreds of thousands of students each year through AP United States Government and Politics.” There will be more to come in the weeks ahead about this program, so watch this space.