In Our Feeds

Melting Icebergs, Deep Freezes, and Expanding Hope: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From delicate balances to hard-wired routines, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Marco Bottigelli/Getty Images

The early hipster gets the empty NYC streets—and the best bodega coffee, which is honestly the bigger deal.

Rise and Grind

My wife and I have a long-running battle about American society’s clear bias for early risers over night owls. I’m a crack-of-dawn guy, happiest when I’m awake before the sun and have the chance to drink some coffee and read the paper before most people have dragged themselves out of bed. That used to mean heading into my campus office before sunrise, working for a couple hours, then taking a long walk in the morning light. Now it’s a desperate attempt to get up before my kids do, claiming a few minutes of quiet before toddler chaos breaks loose. Alyson, by contrast, hits her stride right about 3:00 p.m. and can happily work past midnight, hours after I’ve collapsed asleep with a magazine resting on my face. “Morning person versus non–morning person. It’s a classic duality, isn’t it?” asks James Parker in a great little Atlantic essay from last year. “And, this being America, we’re heavily weighted in favor of productivity and go-get-’em-ness.” It’s been that way from the beginning, says Jess McHugh in the Washington Post. “Whether for health, wealth or beauty, a belief has persisted in American thought that what we do during the first hour we’re awake determines much more than the rest of the day; it just might determine the course of our lives,” McHugh writes. “It’s an idea that originated before Thoreau, stretching back in the American context to some of the earliest thinkers, who believed the early morning hours were key to unlocking the American Dream.”

Ben Franklin was up and moving by 5 a.m. Thoreau took early morning swims at Walden Pond, while John Quincy Adams preferred a birthday-suit-only dip into the Charles River right around dawn. Toni Morrison did much of her writing in the early morning darkness. And modern bookshelves are filled with self-help guides that advise ambitious morning routines. “At their worst, American morning routines can exemplify a punishing meritocracy, a push to always be achieving more,” McHugh writes. “At their best, however, they provide a feeling of freedom and a rare moment for self-determination.” But after 13 years of life with a groggy, get-dressed-by-noon-(maybe) spouse, I can see some of the virtue in the Parker approach of a slower start. “Here’s a truth,” he writes. “Morning people fizzle. They front-load the day, they burn all their energy before 10 o’clock, and the remaining hours are just a kind of higher zombiedom. By mid-afternoon, a morning person is wan and sugar-starved.” He has a point, I grudgingly acknowledge while brewing the mid-afternoon pot of coffee that just might keep me functioning until dinnertime. —Eric Johnson

NASA Earth Observatory

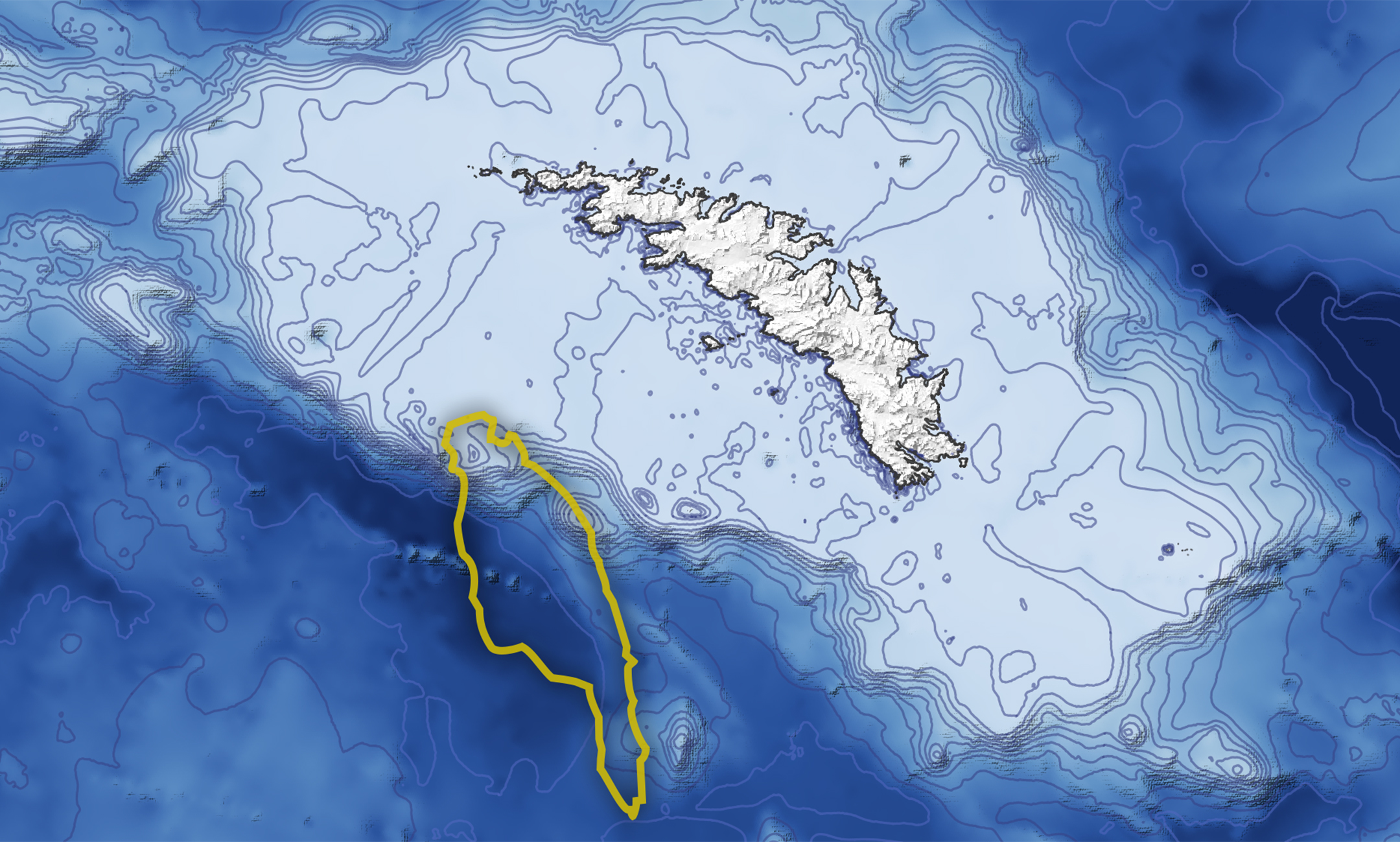

South Georgia Island is the land mass in white. The yellow outline shows iceberg A-68A's location on December 14, 2020. The light blue around the island is every living creature in the vicinity freaking out. ( *not an official scientific fact*)

Falling Water

The movie Titanic taught me the dangers of icebergs—iceberg A68a showed me their complexities. A68a, more than 100 miles long, 30 miles wide, and 800 feet thick, broke off an Antarctic ice shelf in 2017. It floated in the Weddell Sea for a few years before gaining momentum, moving toward the island of South Georgia more than 1000 miles away. Over that journey, the iceberg thinned out and eventually broke into pieces. But while that might be good news for all the Jacks out there, the plankton off South Georgia might not be so lucky. When the massive iceberg melted, it released approximately 150 billion tons of fresh water, full of nutrients like iron that are not usually present in the ocean. Now scientists are studying if and how the massive change to the normally salty water is affecting the environment. One way they did this was by adding trackers to penguins and seals to see if the meltwater changed their foraging behaviors. Fortunately, the animals’ habits haven’t changed, but the effects on plankton are still undetermined. The change in water composition could decrease the amount of plankton or change the types living in the water. Coupled with a decline in the krill population, which resides right above plankton in the food chain, the ecosystem around South Georgia could still be seriously impacted. In a world that is 71% water, but only a tiny percentage of it is potable, the quantity of freshwater in A68a is hard to fathom—and wondrous—to me. When so many parts of the world are suffering from drought, it's sad that so much freshwater can be so damaging. While A68a has not caused a Titanic-level tragedy—yet—it's another reminder that the effects of climate change are myriad, from droughts to the rapid melting of the polar ice caps. —Hannah Van Drie

Oscar Wong/Getty Images

Hope keeps us going through all sorts of maladies and challenges. For some, especially at this time of year, it's hope for a speedy end to winter's deep freeze.

Hope Floats

“Hope is the thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson wrote, a line so quotable that you can find it in book titles, song lyrics, and scrawled across a thousand Etsy posters. Hope is also a thing widely misunderstood, according to new psychology research captured in this moving essay for Aeon. Even in the most dire circumstances, we need to “accept a broader understanding of hope, one that allows the inclusion of difficult truths,” argue David Feldman and Benjamin Corn, both professors who have studied the role of hope in medicine. “Because unpleasant realities permeate our lives beyond the realm of illness, this new understanding may also pay dividends no matter what difficulties we’re facing.” Having studied people facing truly dire situations—a terminal diagnosis, life-altering grief or trauma—Feldman and Corn understand that nurturing hope doesn’t mean holding onto blinkered optimism. A person can be both realistic and hopeful, and there’s wisdom in the ability to imagine a better future even against long odds. “This isn’t because hope has magical powers,” they write. “It’s because, when people believe a goal they care about is possible to achieve, they’re more likely to take steps to make it happen.” Hope can become self-fulfilling, a source of motivation when we need it most.

I had no idea there was something called “Hope Theory” in the psychology world, but it dates to 1989 and a researcher named C.R. Snyder, who interviewed hopeful people in churches, businesses, and community organizations about their basic goals in life. He landed on three core ingredients for hope: goals, pathways (a plan for achieving those goals), and agency (a sense that they could make it happen). “Far from being naive positive thinking, hope is a realistic, yet forward-looking set of beliefs that drives our efforts to bring about a better future,” Feldman and Corn explain. I love that conception of hope because it’s available to all of us, regardless of our circumstances. I’m a pragmatist at heart, someone who wants to know what I can do in any given situation. Hoping for better is a fine first step. —Stefanie Sanford

Warner Bros.

It was supposed to be just a short supply run to the local Walgreen's. But between the supply chain issues and the cold, indifferent universe, well....

The Big Chill

Last weekend, I hauled my family up to the Blue Ridge Mountains for a short vacation right about the same time a major winter storm settled over the region. When we woke up Saturday morning, planning to go sledding, it was about 7 degrees outside. There was a punishing wind that made things feel well below zero. Fresh snow piled into foot-high drifts. My 4-year-old looked out the windows with deep skepticism, so I went on a scouting mission. Within minutes of heading down the hill, my cheeks were numb, my nose tingled ominously, and my double-gloved fingers were moving clumsily. I tried, for a moment, to imagine what it would be like to get stuck in those conditions instead of retreating back into a warm cabin.

“There is no precise core temperature at which the human body perishes from cold,” Peter Stark wrote in a creepy and memorable story for Outside magazine more than 20 years ago. “For all scientists and statisticians now know of freezing and its physiology, no one can yet predict exactly how quickly and in whom hypothermia will strike—and whether it will kill when it does.” I remember reading Stark’s well-reported piece years ago, and it still freaks me out. He does a brilliant job of setting up a plausible scenario—your car skids off the road on a frigid night, and you try to walk a few miles to your friend’s house—that goes from feeling utterly routine to catastrophic in a matter of minutes. “This situation, you realize with an immediate sense of panic, is serious.” That steadily building dread, combined with scientific detail on what exactly happens to your body as life-threatening cold seeps in, makes for great reading (and I won’t spoil the ending). I’m not the only one who found Stark’s story so resonant and terrifying. In an NPR interview in 2019, he talked about why the frozen-to-death narrative became one of his most popular pieces. Things got very existential, as near-death stories do. “You've seen that in the infinite reaches of the universe, heat is as glorious and ephemeral as the light of the stars,” Stark explained. “Heat exists only where matter exists, where particles can vibrate and jump. In the infinite winter of space, heat is tiny. It is the cold that is huge.” A warming—or chilling?—thought as we round out a long winter. — Eric Johnson

20th Century Fox

The author's exact reaction upon reading the "OK, boomer" GIF headline.

Generational GIF Gap

I’m not so delusional to think that the digital culture that proved personally formative should be the end of the Internet superhighway, nor that younger people would have *thoughts* on said culture. But I never expected the kids to come for my GIFs! So when I saw the Vice headline “GIFs Are For Boomers Now, Sorry” cross my feeds I was all like <shocked-dog-face.gif>. Reading the article taught me a lot about this new, most definitely manufactured rift between the generations (the media really wants to make the millennial-Gen Z war happen), but it also made me feel all the get-off-my-lawn vibes. <cranky-clint-eastwood.gif> “GIF folders were used by ancient civilisations as a way to store and catalogue animated pictures that were once employed to convey emotion,” Amelia Tait writes, with what I, someone with a GIF folder on Google Drive, hope is more than a bit of snark. “Okay, you probably know what a GIF folder is—but the concept of a special folder needed to store and save GIFs is increasingly alien in an era where every messaging app has its own in-built GIF library you can access with a single tap. And to many youngsters, GIFs themselves are increasingly alien too—or at least, okay, increasingly uncool.” Hashtag triggered. (Are hashstags still OK?)

One tweet quoted in the piece reads, “Using teams at work has taught me that boomers enjoy using gifs for everything.” To which I’d respond: Is everyone “old” a “boomer” now? Because if so… <homer-disappear-hedge.gif> So why has using reaction GIFs—which, I’d argue, takes a lot more creativity than simply replying with “lol” or a stock emoji—become a sign someone is ready for the retirement village? Syracuse University assistant professor Whitney Phillips says it could be because, during the pandemic, a lot more people—including actual olds—started deploying them, thanks to apps like Teams adding GIFs to their toolkits. Like with rock music, Facebook, and fun before it, once the gray hairs showed up the kids figured the GIF party was over. Another reason, expressed by a 28-year-old podcast producer, is that GIFs are lazy. “I always found them a bit gauche,” she said, “like you don’t really know what else to say.” Shockingly, Tait agrees! “This is how I feel about GIFs—my eyes glaze over when I see them, and they rarely register as something being ‘said,’ but rather seem like the absence of saying something.” To which I say, <nooooooooooooooppppppppe.gif> In my experience, using a GIF well takes time, creativity, and a massive amount of engagement in who you’re talking to and the context of the conversation. “But of course it’s silly to generalise too much about generational attitudes to GIFs,” Tait backtracks, near the end of her 1,500-word generational GIF generalization. But I totally agree! We did it—we bridged the generation gap! <ironic-applause.gif> —Dante A. Ciampaglia