Interview

The Ongoing Mission of a Trailblazing Astronaut

Dr. Bernard Harris made history in space, but on Earth he’s dedicated to ensuring as many students as possible have access to the education necessary for success—down here or up there

In 1995, astronaut Bernard Harris became the first Black man to walk in space, spending four hours and 39 minutes outside the Space Shuttle Discovery during a mission that included a rendezvous with the Russian space station Mir. He left NASA in 1996 and turned his attention to his work as a doctor, inventor, tech investor, and pilot. Harris is also one of the country’s strongest advocates for expanding science and technology education. As the CEO of the National Math + Science Initiative (NMSI), Harris considers it his “terrestrial mission” to make sure more students can take part in rigorous classes that prepare them for a high-tech, high-skilled world.

“If you want to be a contributor to your community, and if you want to make good money and take care of your family and advance your community and our nation, you need this kind of knowledge,” Harris said during our recent interview.

In front of the best Zoom background I’ve seen all year—a photo of the aurora borealis he took on his second space flight—Harris talked about the challenge of bouncing between different schools, the inspiration of a TV doctor, and why we need to expand our notion of which students belong in advanced classes.

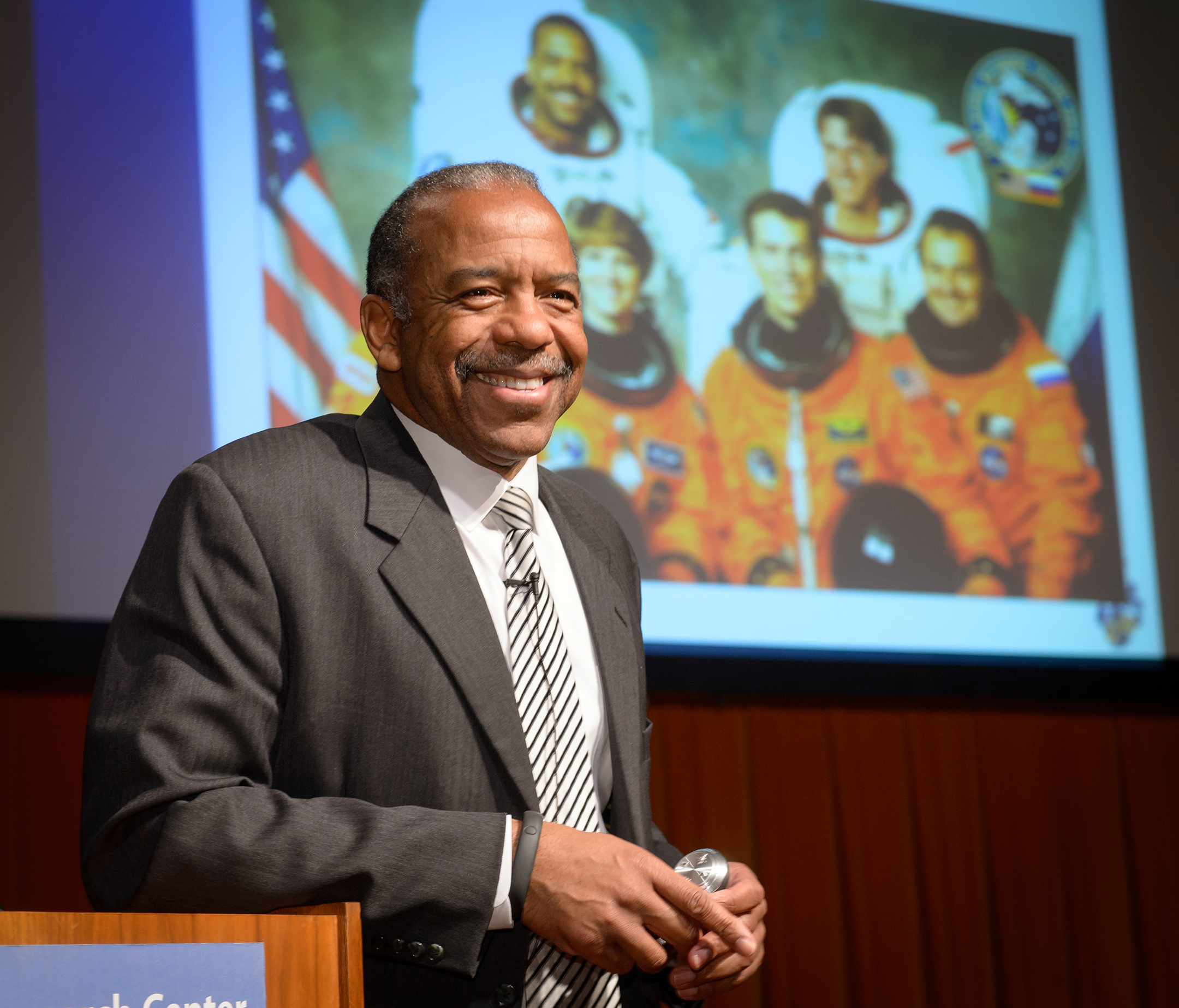

NASA

Dr. Bernard Harris, Jr. at NASA's 2017 Martin Luther King, Jr. Colloquium.

A lot of people dream of becoming an astronaut, but few actually make it into space. Was that something you always aspired to?

I’ve been interested in space since I was a kid, and by high school I had decided to become a physician so that I could qualify for the astronaut corps. That’s how it works—you don’t immediately start training to be an astronaut. You need deep expertise in another field, usually something in STEM, before you join the astronaut corps. I’ve always wanted to help people, and I loved watching Marcus Welby, M.D. when I was a kid. You’ve got to figure out your natural talents and what’s going to be most appealing specialty, and for me that was medicine.

If a student today wants to follow in your footsteps, what’s the right path? What kind of education do they need?

Here’s my road map: No matter where you are, do well! Decide you’re going to be a good student. The discipline for education starts early. Do the best you can at whatever level you are. And think about a focus on STEM—not just to become an astronaut, but because those skills are going to be relevant for 100% of the jobs in this day and age. Whatever you’re going to do in life, you really need some level of expertise in math and science. Then find some profession that suits your skill set. The space program has expanded so that there are so many different fields involved. In one of the astronaut classes we selected the first veterinarian, which makes a lot of sense when you think about it because we do animal studies at the International Space Station. A lot of different careers are represented in the space program.

It’s an exciting time to think about spaceflight. NASA is already talking about sending people back to the moon by 2025, and by 2030 we think we’ll be doing the first launches to Mars. The kids who will be on that mission are in school right now, which is amazing to think about.

NASA

Dr. Bernard Harris in his official NASA portrait.

At the National Math + Science Initiative, your focus is on getting more students ready for the kind of STEM-focused education you had. What made you want to join the organization?

All along—in my career at NASA and in the work I did afterward in health, technology, and business—STEM education was always important. It gave me the chance to do some amazing things with my life. It was appealing to think about the impact I could have for students, to act as a leader for the organization but also serve as an inspiration for the students we’re trying to serve.

We have more than two million students involved in our programs, and more than 65,000 educators. All of that is to accelerate STEM education across the nation, so that when students are getting ready to start their careers they understand the importance of a strong background in science, technology, engineering, and math. The economy, social media, the technologies we’re using every day, the challenges of climate change—all of that is driving the need for knowledgeable people in STEM. If you want to be a contributor to your community, and if you want to make good money and take care of your family and advance your community and your nation, you need this kind of knowledge.

I had my NASA missions, and now I think of this as my terrestrial mission. I see it as a ministry of a sort.

What are some of the key things you’re working on at NMSI?

We’re very focused on expanding access to high-quality classes like Advanced Placement. In a lot of the communities where we’re involved, they may not have many AP classes available, so we have to get them educated on why they are so important and what it means for their students. But our job is not only to get AP into those districts but to help teachers identify students who wouldn’t normally be considered AP material. We help them set goals, remove barriers to signing up for the classes, and really expand the criteria of who should qualify for AP. In many communities, there’s an assumption that if you have a minority student then maybe they don’t have the aptitude to take a rigorous class. And that’s just not true. If you expose them to the course and set high expectations, you can transform the school and transform the district. And you can change students’ lives.

Have you seen evidence of how those students perform in AP?

We have a lot of data on this, actually. We’ve followed students into and through college, specifically looking at their aptitude toward STEM in the majors and careers they’ve chosen. It’s exciting to see how strong the results are. We’ve even noticed that students with a score of 2 on an AP exam are prepared for the rigors of college. They may not get college credit, but it shows they’re ready. I have college administrator friends who say the biggest issue with incoming students is their lack of preparation academically. AP provides that preparedness.

College Board/YouTube

Dr. Bernard Harris (second from left) on stage at the 2019 College Board Forum, speaking on a panel about Two Codes with (from left) Reshma Suajani of Girls Who Code, DeNora Getachew of Generation Citizen, and moderator Stefanie Sanford.

NMSI is also working to expand AP access for military families. Tell me why that’s important for military-connected students.

We’ve been involved with Department of Defense for quite some time. Our College Readiness Program is deployed in military-impacted schools to help students, families, and teachers stay focused on the path to college. It’s harder in some ways for military families. I’m the product of a military family, and every year or so, every six months, you’re moving from base to base. Your education may not be consistent, depending on where you go. But with AP, a student can start the course in one high school and pick up right where they left off when they move to a new school. AP is a consistent program, so this is the DoD’s way of investing in the quality of education for families all over the world.

As you were moving around a lot, was there a particular teacher who stood out? Which teacher had the deepest influence on your education?

That’s an easy one: my mother. She spent 45 years teaching third grade. I don’t know how she did it, but she loved it. She brought that love of education home, and she checked in with us along the way: What do you want to do when you grow up? What are you going to major in in college? She forced me to think about that, then gave me the support to do whatever it was I wanted to do.

I spent a big part of childhood growing up in the Navajo Nation, where my mom worked as a teacher for the government. So before I wanted to be an astronaut, I wanted to be an Indian chief, a medicine man. Then my cousin became the first fireman in the family, so I wanted to do that. And then my stepfather was a police officer, so I thought about that. I went through all those different things until 1969, when I saw Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong walk on the moon, and I thought, That. That’s it. I want to do that. And I believe when you really hold something in your heart, the universe conspires to make it happen.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.