Profile

Pioneers in Computer Science: Roy L. Clay Sr.

After helping HP develop an early microcomputer, the Godfather of Silicon Valley built a hub for the developing tech industry

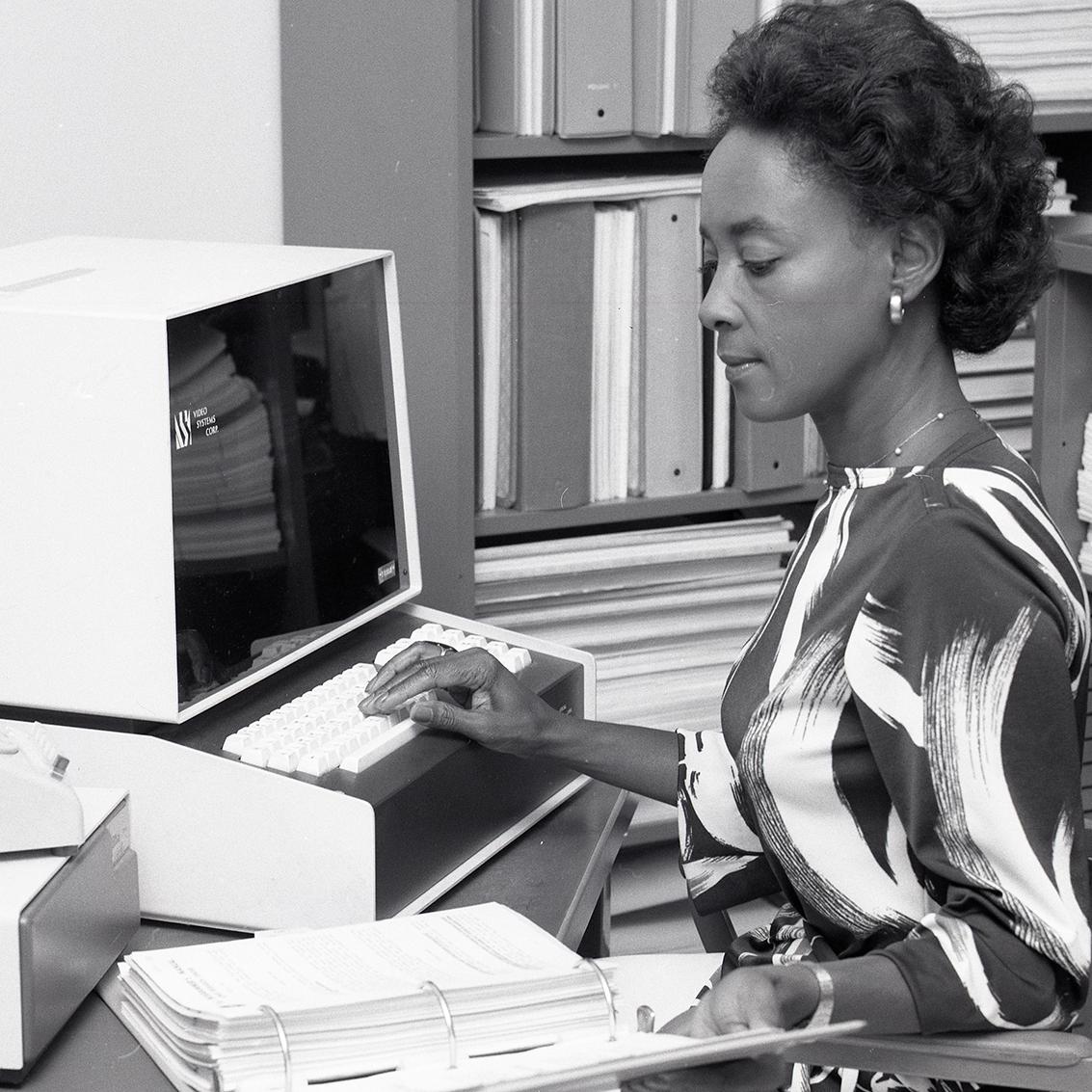

Courtesy of Heritage Werks/HP archives

Roy L. Clay was the lead developer on the HP 2116A, the company’s first minicomputer.

“Mr. Clay, we are very sorry but we have no jobs for professional Negros.”

That was the attitude that greeted Roy L. Clay Sr.—who has been called “the Godfather of Silicon Valley”—in one of his first job interviews after college, at McDonnell Aircraft. Born in 1929, in Kinloch, Missouri, Clay was no stranger to discrimination. He overcame poverty (his home had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing) and deep Jim Crow racism to become, in 1951, the first Black graduate of St. Louis University, and, later, a founding father of the American technology industry.

It nearly never happened.

As a young man, he earned an income pulling weeds and gardening in nearby Ferguson. After one particularly hot late-summer shift, he bought a soda and left the store. “I was not permitted to consume the drink inside the store, so I sat on the curb outside,” Clay wrote in 2014. Ferguson police soon arrived, questioned young Roy, handcuffed him, put him into their car, and drove for about a mile to a spot near Baileys Pond. “I envisioned the worst, including how I would escape if I were taken toward the water,” Clay remembered.

He was let go, though, and given a warning never to be seen in Ferguson again. He walked back to Kinloch, never looking back in the direction of that intersection. “When I reached home, I told my mother what I had experienced,” Clay wrote. “Her response was, ‘You will experience racism for the rest of your life, but don’t ever let that be a reason why you don’t succeed.’”

And he didn’t. He was a top student at Douglass High School, and a trailblazer at St. Louis University. After graduating, his mathematics degree in hand, Clay set out to build a career—and he wouldn't take "no" for an answer.

Palo Alto Historical Association

Roy L. Clay in his office, 1986.

Leaning on his interest in computing, he taught himself to code and, in 1956, returned to McDonnell Aircraft. This time they hired him, as a computer programmer. Two years later, Clay was in California, working at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory writing software for the Energy Department to gauge possible radiation dispersal patterns caused by a nuclear explosion.

This caught the notice of David Packard—cofounder of, yes, Hewlett-Packard—who hired Clay in 1965 to lead HP's computer science division and develop and write software for the HP 2116A microcomputer. Roughly as big as a typewriter, when it hit the market in 1966 it was the second such machine in the world and a crucial building block in the personal computing revolution.

After clashing with Bill Hewlett, Clay left HP, was elected Palo Alto's first Black council member in 1973, and three years later became the city's vice mayor. In 1977, he founded ROD-L Electronics, which innovated technology that kept early computers from possibly shocking users or catching fire. In 2003, Clay was inducted into the Silicon Valley Engineering Council Hall of Fame.

Clay was also a savvy investor. In the ‘70s, working as a computer consultant for Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers (one of the most influential Silicon Valley venture capital firms), he funded, among others, Intel and Compaq.

At every step, Clay also created programs to create pathways for Black computer scientists into Silicon Valley, which, when coupled with his career achievements, earned him the "godfather" superlative.

"My sole interest is to work with young Black males to encourage them to learn how to do things well," Clay told Forbes in 2015.

An entire industry—to say nothing of our digital culture—have benefited from the interests of Roy L. Clay Sr.