Interview

Salvation on the Water

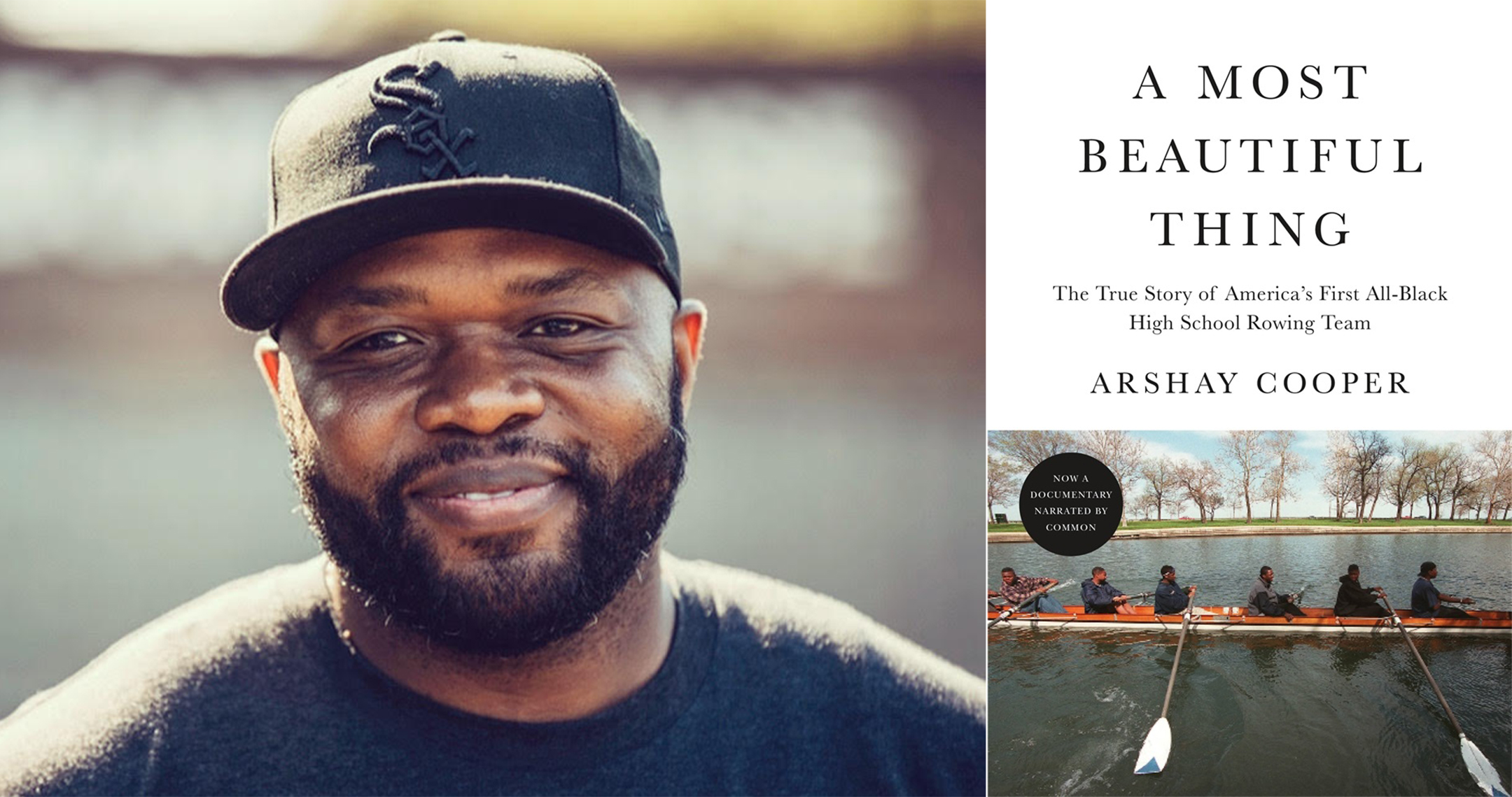

Author, activist, and rower Arshay Cooper, who was part of America's first all-Black high school rowing team, discusses his new memoir

Living on the West Side of Chicago in the 1990s, teenager Arshay Cooper was surrounded by drugs, gangs, and very little opportunity. His father wasn’t around. His mother would disappear for days, looking for a fix. School was hardly a safe place. Arshay, who dreamed of becoming a chef, would seek refuge in writing poetry and watching shows like A Different World and Fresh Prince of Bel Air, which presented positive views of what a Black teenager could accomplish. But it was a very unexpected sport that changed his life.

A notice was posted in the Manley Career Academy High School recruiting for a rowing team. Arshay’s friend Preston convinced him to check it out. Neither of them had seen an erg machine or a crew boat, and neither were comfortable with being on the water. But they come back the next day, and the next, eventually bringing more friends and making new ones—Malcolm, Alvin, Pookie G.—as they tried out for and became America’s first all-Black high school crew team. That brings them into a White-dominated world of privilege, where they’re often seen as a novelty at best, and criminals at worst who don’t belong on the water. But they’re also introduced to coaches and other adults who open up opportunities—for travel, for college, for entrepreneurship—that they never imagined possible.

After spending time in the food service industry, Cooper, who still rows, is a motivational speaker and activist who works to bring rowing into low-income communities. He revisits his high school experience in his recently published memoir A Most Beautiful Thing. It was the basis for a documentary with the same title, released in July. Narrated by Common and directed by Mary Mazzio, a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic rowing team, the film follows Cooper and his friends as adults looking back on what they went through as teenagers and getting together for one last race.

Cooper spoke with The Elective about the book and film, how rowing has changed, and the impact this story can have in our current dialogue about race and policing.

Clayton Hauck/courtesy 50 Eggs Films (author), Flatiron Books (cover)

Were you writing the book and making the documentary at the same time?

The book was self-published in 2015 as Suga Water. Mary Mazzio read it and wanted to do a documentary, and in the process I was introduced to a literary agent who said she would love to get the book out to a broader audience. They gave some feedback, like, maybe we can cut this and cut that, and then it was republished as A Most Beautiful Thing. But it's the same overall story.

When did you realize this was a story you needed to tell, and that this was a good time for it?

I'm still a rower, and I help folks start their rowing programs. I speak in schools, especially in Chicago, and I see the younger version of myself, Alvin, and Preston in every school I go to. The question that gets asked a lot is, "How do I live here, with all the circumstances that are happening and become successful if I can't play ball, or if I can't rap, or…. ?" I answer the best way I can by telling them my way. And I wanted to get that answer out into the world for all young people. So the initial thought was to write it for young high school kids who grew up like I did.

courtesy Arshay Cooper

Members of the Manley High crew team work on their boat during a practice.

In the book, you recount how you and Preston, and later your other friends, see the sport, the rowing machine, and the boats for the first time and are completely confused, and then being afraid to get out on the water. When you talk to kids now, what is their reaction to rowing?

I was at a school in Harlem eight or nine months ago, recruiting for this rowing program in New York, and a kid yelled out, "Have you seen Titanic?!" It was hilarious. It's like, "We're not drowning! We're not doing that!" So the reaction is the same. This sport is still not mainstream. It's still not introduced to schools in neighborhoods that normally don't have access to this sport because it's so expensive. But I think what's special about this film is that when I mention Dwyane Wade is a part of it and Common and Grant Hill, and there's a trailer to see people who look like them actually do it and look cool, the response is now different. I didn't have that before. As I wrote in the book, representation matters. When I watched A Different World and Fresh Prince of Bel Air, I was, like, "Wow, you can go to college and be successful, even if there's not a dad in your life? I can do all these amazing things." So I think now that we have this film and this platform, it makes it a little easier because now they see someone who looks like them doing it.

Craig Nash says in the film, "You can't be what you can't see."

That was great. I remember seeing the film for the first time and sitting in the back and when he said that, I saw a lot of heads nod.

Does having gone through this experience help the young people you talk to you listen to your story more or maybe see the path forward a little bit better?

Yes, so much better. When I first walk in, I see how they look at me, and a few minutes later I see the light bulbs turn on in their eyes. The fact that a young man whose mother was a drug addict, who never said the word "dad" a day in their life, who failed the eighth grade and now is an author, has traveled the world, and has spoken to thousands and thousands of kids, and one of the things that bridged those gaps was sport? I think that gets their attention. There are so many people who didn't make the basketball or football team or baseball team that are looking for opportunity. There are so many young people who don't feel athletic, but maybe they can get a shot at this. So that really gets their attention.

You write that in high school you felt this tug of war between the you in the boat and the you that the world expects. Do you still feel that conflict?

As an older person, I don't think that way anymore; I've seen so many great things and had success through the sport. At that time, we shared the boathouse with high school kids who were pulling up in nice cars, so being back and forth from the West Side, in this neglected community, to travel to a community that was not neglected at the boathouse, kind of messed with my head a little bit. You'll be in your neighborhood and you'll watch the news and they say, "Statistics say you're gonna die before blah blah blah," and I felt like that's what the world expects. In crew, things changed. I was traveling, I was visiting colleges, my coaches were, like, "You're amazing. You're awesome. You're strong. You're powerful." I was exposed to this different world. When I'm in this boat and things get hard for me or that doubt, that fear kicks in, like, "Do I belong if I lose? Should I be here?”—I do belong here. That's the mental part I had to deal with all the time in the water.

courtesy Arshay Cooper

The Manley High crew team with their coach, Marc Mandel (middle).

Crew is a sport where a lot of rowers work and train for the Olympics. Did you and your friends ever think about getting to an Olympic trial or the Games?

We didn't talk about it much, but it was something I thought about because you hear so much about how it's an Olympic sport. Around that time, I didn't know—because our coaches didn't know—but the first Black male rower, Aquil Abdullah, was training to be in the Olympics. I told him recently that if we knew about him and he knew about us and he came to our school while he trained for the Olympics and he said, "Hey, this is what I'm doing. This is who I am. And you can get there," I think it would have changed my whole thought process. But because of our conditions, I was so caught up, not in the competitive part of rowing even though I competed, but the meditative part, just to change and the entrepreneurship and how we make money or become a chef or get a job. That kind of outweighed some of the things for all of us—how do we survive?—and I think we didn't think much about the Olympics because of that.

You write that the water was your peace. Is that still the case?

Oh, yeah—even when it rains or in the shower or an ocean. I never say "swim test," I say "water confidence" because when you say that it's different. It just clicks differently and mentally. But building a relationship as a young person with the water really helps you in your future. It's something you can go to and talk to and just, you know, relive things. So yes, it's still there. When we trained for the race in the film, me and the guys went out and had a good time, and being in the water, being away for a little while.

50 Eggs Films

Former members of the Manley High crew team in a boat with officers from the Chicago Police Department. The two groups competed together in an amateur race.

In the 20 years since you and your friends became the first all-Black high school crew team, what kind of change has there been in representation in the sport, generally and at the youth level?

Not a ton, but way more. What I mean is, when I came back to the sport almost as an activist in 2015-16, there were a few programs that were really diverse. That was in New York, Baltimore, Chicago. And then there are people who have heard my story that are looking to start this kind of program. I help and work on a framework on how to start that, how to recruit, how to build partnerships with schools, and how to fundraise. I've spent a lot of time traveling throughout the country helping build these programs and diversify all-White programs. Rowing in general is still, like, 2%, 3% diverse. But it was way less than that. And I think slowly it's starting to grow. I'm seeing, like, 40 athletes of color rowing on the college level, and more and more youth and more and more programs. Again, that still doesn't compare to all the folks who are rowing, but more and more every year we're seeing more people that look like me in the sport.

Do you ever run into resistance from a community or school?

Yeah, some public schools are worried that the kids will drown or, "Our kids won't do that," or there's an insurance issue. And there are some clubs where old guys who've been on the board for a long time say, "I don't want to diversify my club. I've got to worry about kids stealing purses.” Crazy, stupid stuff like that. So there is some resistance. Some of these old-school people are used to the Harvard, Yale, Princeton kind of atmosphere in the sport. For me, it's simple: Here are some communities that really need opportunities, and here is a sport that really needs diversity and more talent. Why not make that work?

I can only imagine the systemic issues you run up against.

Number one, it's expensive to play soccer now in some of these programs—and that’s a sport where all you need is a ball. So imagine rowing, where the boat is the same price as a car. It was easy for me and the guys to pick up a football, find a place to play football or go to a court every day and play basketball, or pick up a stick or branch or bat and play baseball or softball, but we couldn't just roll up to some boathouse and be like, "Hey, we want to row and race." We'd be told, "OK, it's $300 a season." So that's why the sport is still the way it is. We have to figure out how to get access. It's still so rich, White, and wealthy. There's a lot of work to do.

50 Eggs Films

A moment from the film "A Most Beautiful Thing."

You write in the book that your goal wasn't to change the sport but to add to it. When you look at all that you've done since high school, what do you think you've added to rowing?

More brown faces. I don't want to change what the sport does for you individually. People say, "Oh, you're changing the sport!" I want to add to it, and what I want to add is brown faces. The history of sports, they do make significant impacts in some way but they don't entirely reach their goal without the power of diversity. When more brown people are in the sport, more people begin to interact with each other. They begin to understand each other. Diversity is celebrating differences and understanding each other. I want to make sure that in every city, every country, the rowing team reflects their diversity. That's what I'm trying to add to the sport. It's very slowly happening, but it's happening.

You and your friends all had bad experiences with police in Chicago, and in the documentary you bring officers from the Chicago Police Department to row with you. It’s impossible to watch those scenes without thinking about what’s happening in the country right now. What impact do you think the film and the book can have?

When you look at the history of sports, it unites people. But you need that crazy, kind of radical coach who’s like, "Enough is enough, I'm going to go out and do something," and kind of fans the flames in some of the other young folks. In the '60s there were many different movements. There was the MLK movement with civil rights, there was the Malcolm X movement, there was the Black Panther Party movement, there was the James Baldwin way, there was the NAACP way. My way is very personal and guided by sports, and I think bridging the water has connected folks to want to see change and want to see diversity in a sport. That becomes a part of your life, and that becomes a change they want to see in the world.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.