Interview

School Days Influences: Meet the Curators Behind the Met

A job curating the collections at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of the most prestigious in the art world. Seven current Met curators share the educational and personal journeys that earned them that coveted position.

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is not only the centerpiece of New York’s cultural landscape and tourist economy—in 2019, it welcomed nearly 6.5 million visitors, the fourth-most worldwide—it’s one of the most important museums in the world. Millions of art lovers come to the Met to see paintings by masters from the Renaissance through the present day, from the West and the East; halls of Greek and Roman statuary and architecture; the only complete Egyptian temple in the Western hemisphere; and exquisite period rooms, fashions, and ancient artifacts. (And let’s not forget the annual Met Gala, which most people experience through their screens but is one of the most high-profile events of the year.)

And that’s just for starters. Founded in 1870, the encyclopedic Met collection now comprises some 36,000 objects from 5,000 years of human history. You can visit for years and still not see everything, like lifelong New Yorkers who make regular pilgrimages to the museum.

Behind the scenes, the Met’s curatorial staff—spread across 17 departments—organizes, cares for, and ensures the safety of all of that art. A curator position at the Met is among the most prestigious museum jobs in the world, and it can represent the apex of a career studying, working with, and loving art.

But what kind of education experiences help curators bend their career paths toward the Met? The Elective spoke with seven Met curators from a diverse range of departments, including C. Griffith Mann, the Michel David-Weill Curator in Charge of Medieval Art at both the Met Fifth Avenue and The Cloisters; Maia Nuku, the Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator for Oceanic Art; Jeff Rosenheim, the Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of Photographs; Sylvia Yount, the Lawrence A. Fleischman Curator in Charge of the American Wing; Keith Christiansen, the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of European Paintings; Nadine M. Orenstein, the Drue Heinz Curator in Charge of Drawings and Prints; and Navina Najat Haidar, the Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah Curator in Charge of Islamic Art.

"The Dance Class," Edgar Degas (French, Paris 1834–1917 Paris), Bequest of Mrs. Harry Payne Bingham, 1986, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Where did you go to high school? What habits or hobbies did you develop during your high school years that now contribute to your work as a curator?

C. Griffith Mann: I attended Greenwich High School in Greenwich, Connecticut, a large public high school with some exceptional teachers and a broad range of non-academic programs. I took art classes throughout my high school career, and was always drawing, an interest I developed as a young child in Ankara, Turkey, where I lived until fourth grade. My AP U.S. History course, taught by Mr. Kazanis, used Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States as a textbook. This is when I learned that there are many different ways of interpreting the past.

Maia Nuku: I grew up in London and went to St. Paul’s Girls’ School in Brook Green, an independent day school for girls. We were encouraged to try things out as a way to ignite our interests and spark our curiosity, so drama/theater, music, art, and poetry were all part of our day alongside academic study. They supported girls in science, offering us technology and woodwork courses alongside the usual curriculum, which was ahead of its time for a girls’ school. I think it’s really important not to specialize too early or fixate on following a specific trajectory at school.

One isn’t ever fully aware of the jobs and possibilities that are out there. Keep your options open and be true to yourself: the skills you learn doing one thing will always come in use later in life, often without you even realizing. I was involved in the school magazine, doing layout, editing photos, making up captions for the images. I loved fashion magazines and used to cut up my issues of Vogue, rearranging the runway pictures while I listened to music. I was in the film club and loved to go to independent film festivals to watch foreign language films. You can learn a lot about a country from their cinema—it’s like a distilled vision of the culture. I love dance and enjoyed going into London to see live performances: ballet, flamenco, avant-garde companies. My friends and I used to travel up to London on the weekends and escape into nightclubs so we could listen to music and check out the scene. It was the late ’80s/early ’90s and a really vibrant time. So that mix of visual culture is in my DNA. It’s always been a big part of my life. I absorbed it and noticed it and reworked it in my mind’s eye.

Jeff Rosenheim: In high school, in St. Louis, Missouri, I taught myself camera and darkroom work learning the medium through books and magazines. By my junior year, I ran a small business making yearbook portraits for graduating seniors.

Sylvia Yount: I graduated from a midsize public school in New York’s Hudson Valley, about an hour north of Manhattan. While I was raised loving art and visiting diverse museums and historical sites across the country, my focus during those years was on art-making and music—I painted and played the flute—and even considered applying to music conservatories after high school. I’m not sure I really knew then what was involved in “curating,” but I do recall having an inspiring AP European History teacher who shifted the curriculum from political and military topics to art and culture, which offered early exposure to the discipline of art history.

Keith Christiansen: I went to Clayton Valley Charter High School in Concord, California, which is a suburb of San Francisco/Oakland. Aside from tending the yard, my real hobby was drawing and occasionally writing poetry. (I don’t do either now, but I can see that they were important.) I played the cello, which led to my love of classical music.

(clockwise, from top left) Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Sheen Center, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art

(clockwise, from top left) C. Griffith Mann, Sylvia Yount, Maia Nuku, and Nadine M. Orenstein

Nadine M. Orenstein: I grew up in New York City and went to the High School of Music and Art, now the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School. If you know the movie Fame, my school was the sister school of the one in the movie. In fact, several people in my class were in the movie. A friend from high school remembers me saying at the time that I wanted to be a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That didn't come out of the blue—I was always interested in making art and I spent a lot of time in museums, especially the Met. On days off from school, I would meet friends on the steps of the Met and we would go around the museum for a little while and then move on to other things in the city.

In the ’70s, my mother wrote about contemporary women artists, so I knew artists, curators, and people involved in the art world. In high school, we had two hours of art classes every day, which was great and liberating, but I realized through knowing artists that being one is a very tough career. My parents and many other members of my extended family are university professors in different fields, so there was a certain way of thinking within the family that you should get a doctoral degree and, if nothing else, you would have that to fall back on. So I was pretty clear in high school about what my path would be: I would go into college and then go on to graduate school.

Navina Najat Haidar: I went to a boarding school in the lower Himalayas. It was quite remote and there was little communication with the outside world for most of the year. But we were surrounded by nature and there was a large art room where I spent a lot of time. I developed my interest in drawing and painting, as well as in looking at other students' work in the display area. At that age one is always influenced by one's peers, but I tried to find my individuality and learned to recognize it in others. That taught me to be both an insider and an outsider in my professional path.

Where did you attend college/university, and what sorts of skills did you develop during your time there that you now utilize in working as a curator?

Mann: I was an undergraduate at Williams College, where I started on a pre-med path thinking I would pursue a career in medicine. After a year on campus, I took an art history course and realized that this subject allowed me to combine an interest in studio art with an interest in history. It was at that point that I started visiting museums, looking at things more carefully, and realizing that art could open windows into different time periods and human experiences. The skill I learned at Williams was looking closely, paying attention to how things were made, and writing about something visual.

Nuku: My first degree was in modern languages (Spanish and French) at Manchester University in England. One of the reasons I chose to study languages was the prospect of travel. I lived overseas in the third year on a study exchange with La Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso in Chile and tailored my schedule to follow and deepen my personal interests. It was totally immersive. Pablo Neruda’s poetry was the original spark that drew me to Chile, and I took courses in design and architecture, Latin American literature, history and, poetry, and really soaked up the country and its arts scene. I joined an open-air mural arts project in el barrio and got involved helping to paint large-scale murals that had been designed by local Chilean artists and included contributors like Roberto Matta. It was there in Chile that I first became exposed to grassroots-led community art projects and saw first-hand the benefits of bringing people together through art.

Rosenheim: I attended Yale University, where I continued my learning about photography and its practice through art and art history courses, as well as through the lens of 19th- and 20th-century cultural history.

Yount: I was an Italian major at New York University—at one point thinking I might want to explore working at the United Nations!—and I had the privilege of spending my final semester of college in Urbino, Italy, through a State University of New York at New Paltz study abroad program. Walking the streets of that extraordinary Renaissance jewel of a town—and coming into contact with curators and conservators for the first time—I redirected my attention to museums. There’s no question that an ongoing interest in the importance of “place” in my scholarship, with a focus on regional art worlds, began in that special setting.

Christiansen: The University of California opened a new campus in 1965 at Santa Cruz, set in a redwood forest. That’s where I chose to go, and it was the right choice for me. Part of the first two years was a world civilization course—first year European history from the Greeks to modern times; second year American, Chinese, and Indian—that was taught by amazingly gifted teachers, with readings from primary literary sources. It has formed the backbone of my intellectual life.

Orenstein: I went to Barnard College in New York City. It may sound like I am a devoted New Yorker who never moved away, but my father is French and we spent a good deal of time in Europe while I was growing up. At Barnard at the time there was a Winter Break internship program that I took advantage of each year that I was there. Through that program I took part in internships in a gallery, a large museum, and a small arts organization. That was really helpful in clueing me into what goes on in those places. I recommend to anyone interested in the arts to do internships just to see if what actually goes on in a workplace matches what you imagine goes on there.

For instance, when you think of museums, you may think of hanging exhibitions, giving tours, and going to wine and cheese events. That is really only a small part of the job. In reality, there is a lot of administrative work involved and you have to be quite detail-oriented—making lists, typing artwork into databases, keeping track of budgets, and following templates, things like that. You need to know about art, but it also helps if you are good at organizing. Some people are surprised by that aspect of museum work. I picked up many useful skills for my present career along the way in college, like how to do research and think critically about what has been written. Very important for museum work is language skills. By the time I got to college, I knew French and could understand Spanish. In college, I took German—a lot of scholarship on art of all kinds was written in German. It is important to be able to read it, and many graduate programs require that you pass a German language reading test.

Haidar: I did my PhD at the University of Oxford in art history. The approach there emphasized style, chronology, and connoisseurship. All those elements were very valuable for a museum career.

Looking back, was there something unique about your particular campus environment, geography, or regional culture that impacted the development of your skills?

Mann: Williams is in a remote setting but has amazing museums in the area, and professors assigned work that ensured we were visiting museums on a regular basis. During my senior year, I spent much of my time at the Clark Art Institute, where I discovered that large research projects could be both challenging and rewarding.

Nuku: Wherever I have lived or worked, the constant has always been art. I love to keep my finger on the pulse of culture. The first thing I do when I get to a city is visit the museum, check out the gallery, pick up the local art-zine in the café or bar. I love the space of museums, the architecture, the distillation of ideas through the juxtaposition of “things” with words. It’s a unique form of expression that has evolved over several centuries, and it’s a powerful one if used responsibly and critically as a lens on humanity.

Studying languages was a good strategy. Throughout my school life, and even at university, I didn’t have a clear idea what I wanted to do. I made choices that ensured plenty of avenues remained open and tried to keep myself open to opportunities with overseas travel and trying out different jobs in different industries to see where I landed. I think the trick is to keep checking-in with yourself every 3-4 years to see how you feel things are going: Are you enjoying it? Do you find it fulfilling? Do you still feel passionate about what you are doing? Keep on writing. It’s a creative skill that you hone, just like any other. It has helped sharpen my critical faculties and guided me towards unpacking what I am looking at. What is being said, and, more importantly, what is not being said? Reading, writing, and engaging has taught me how to think critically, how to listen, how to express my views.

Rosenheim: I was quite lucky to have two mentor professors who took me under their wings and actively guided my development: historian Alan Trachtenberg and artist Richard Benson. Sadly, both have passed.

Yount: Of course, being in Manhattan—with so many museums and galleries at my disposal—was important. However, I’m embarrassed to say I did not take a single art history class in my time at NYU, even as I studied art in broader cultural contexts. Having that immersive opportunity later in Italy—on-site, as it were—led me to value working directly with historical art objects, rather than just studying them at a remove.

Christiansen: UC Santa Cruz has an amazing teaching staff and a great sense of community, with a once-a-week common dinner where students ate with professors and a once-a-month evening when a guest would lecture or play music or give a poetry reading. These events introduced the student body to a wide spectrum of culture and were incredibly important. Another aspect was the spectacular setting in the redwoods, with the sense of a dedication to learning.

Orenstein: Being in New York at Barnard, with so many wonderful museums and galleries close by, allowed me to intern in a variety of organizations, including the Brooklyn Museum and Franklin Furnace Archive. My freshman year, I went to the career services office to look for part-time jobs and there was a posting for the job of usher in the Metropolitan Museum’s auditorium. I applied for the job along with a friend and we worked as part-time ushers that year. After that, I got several jobs in the museum’s gift shops. I can’t say that being an usher got me to where I am today, but it showed me the museum from another angle. And in the end, they couldn’t get rid of me!

Haidar: At Oxford, art and history were not just confined to museums. There were historical buildings, sculpture, and paintings, and more all over the campus. Living in that environment taught me to connect art to life in a wide way, which has helped my career.

How long after college graduation did you begin to curate art professionally? Did you develop any habits or skills in the interim period that you utilize?

Mann: Following college, I worked as a school, youth, and family program intern at the Brooklyn Museum. This experience was fundamental to my work now, and made me realize how hard you had to work to make art relevant to a wide range of audiences. I loved the high school kids who pushed and challenged me, forced me to step up my public speaking skills, and taught me how to express my passion for the visual arts. These kids also taught me how important it is to understand your audience.

Nuku: I had a whole other career before I found my path into art and the museum world. After I left university with my first degree, I worked in the city of London for 10 years during my twenties. It was a great place to get experience and cut my teeth in the business world. I did a graduate training scheme for a brokers’ firm in the specie market, insuring fine art, diamonds, gold, and bullion for Lloyds of London. We worked with all the major U.S. museums and cultural institutions: the Guggenheim, J. Paul Getty Trust, Barnes Foundation, and so on, and I had the opportunity to travel and learn about business and the corporate world. After a decade, I could do the job but I realized my soul wasn’t being nourished and, without passion, I was always going to falter. I took a deep breath and decided to leave and lean into the hunch that I had always had about art and museums. All I had to do was follow the thread that had been continuous in my life. So I made the decision to go back to study, focusing on art history and a move into curating.

I opted to study at the Open University, which is a distance learning model where you build credits with a range of courses you select for yourself. The Art and its Histories course I took was grounded in critical theory and opened my eyes to the histories that have been elided from the conventional canon of art history promoted and upheld by the art world. The courses went against the grain and punctured accepted histories, drawing out distinctions, such as craft versus art, and highlighting the power dynamics and political hierarchies that have led to the elision of women artists and the marginalization of Asian and African art. In fact, the Pacific wasn’t even on the curriculum. Oceania has always been at the margins of the margins! That’s OK—eight years after I studied the course, I was helping rewrite the syllabus. The project of history and art history is constantly being reevaluated, which is what keeps it dynamic and fluid. If we can unpack those histories and reinterpret them for our times, we can understand ourselves better.

Rosenheim: I curated my first exhibition while still an undergraduate student: a retrospective of the American photographer Walker Evans. The show was accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalog and was presented at several venues in Spain and Italy. I started my museum career as a curator in the fall after my college graduation.

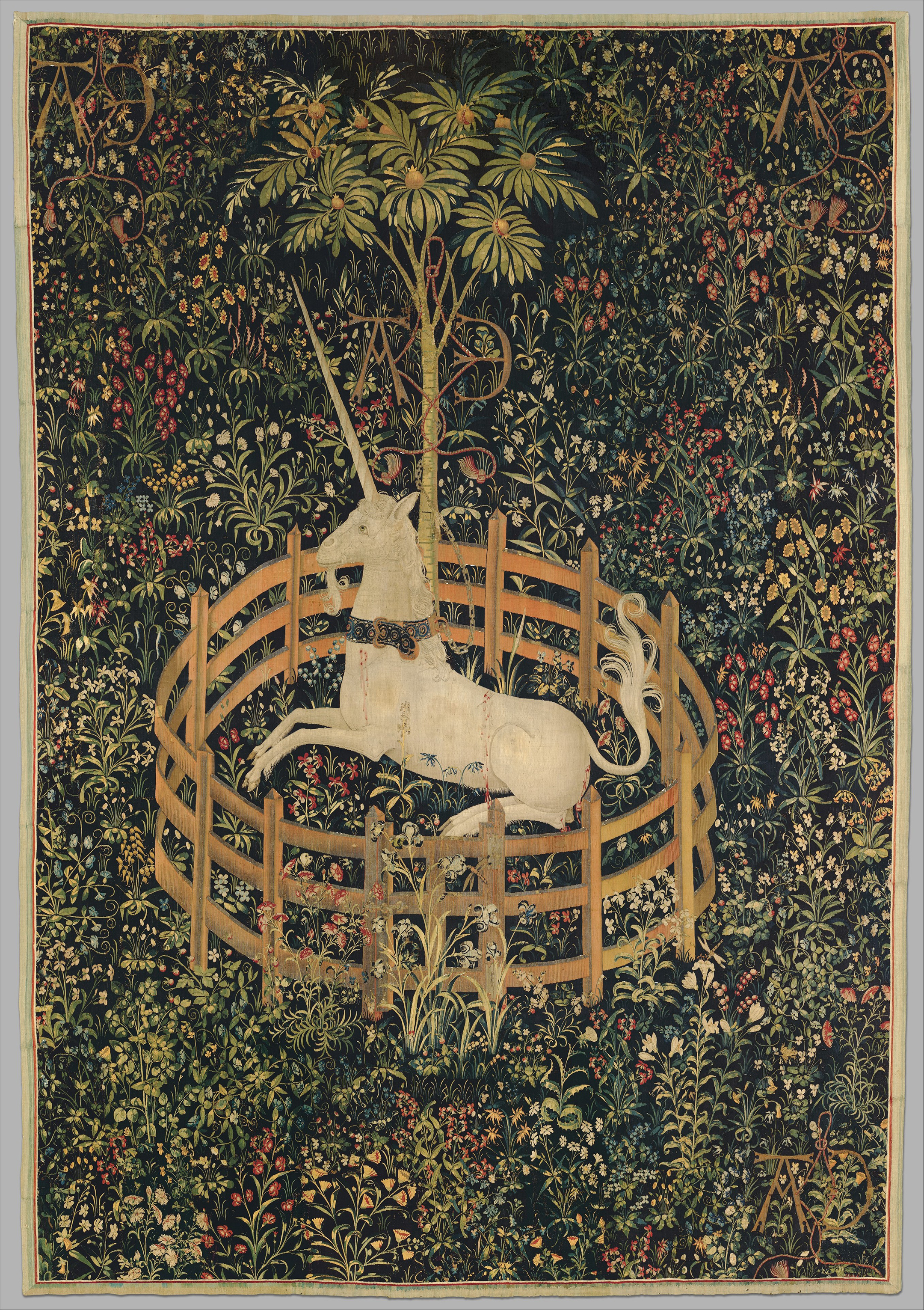

"The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (from the Unicorn Tapestries)," French (cartoon)/South Netherlandish (woven), Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Yount: I graduated from NYU a semester early—on my return from Italy—and was lucky to get an entry-level job at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, working with the director on a publication about Mrs. Gardner’s remarkable life and work, which allowed me to utilize my Italian skills. While the Gardner was not a collecting institution, I learned about general museum practice and found I was most drawn to curatorial work, which required an advanced degree. I secured my first curatorial position, in Philadelphia, while finishing my Ph.D. dissertation on late 19th-century American art. From there, I moved on to museums in Atlanta and Richmond before returning to New York to head the American wing at the Met—a career trajectory in which the common thread has been my interest in expanding the canon of artists to be more inclusive and ensuring my professional practice is grounded in socio-historical contexts that resonate with visitors today.

Christiansen: I went immediately to UCLA for graduate work in medieval studies, switching soon to art history. It’s important to remember that there was something called the war in Vietnam going on: the idea of an interim period really did not present itself. There was a draft looming. This proved a pretty ominous incentive to make decisions.

Orenstein: It took me about nine years between graduating college and landing my first real full-time job as a curator. But that time was mostly spent in graduate school. I feel very fortunate to have landed where I am today. There are not a lot of jobs in this field, so I like to tell people that you have to have every degree and qualification in the world and then be at the right place in the right time with all the stars aligned and have someone notice you.

After college, I went directly to graduate school at the Institute of Fine Arts in New York. I got my MA and continued on to the Ph.D. The Institute is located a few blocks from the Metropolitan Museum, and that was important for getting my foot in the door. Most important for me was the curatorial studies program that I participated in as I was working on my PhD course work. Each of the three classes in the program involved working with someone at the Met, and by chance the second class was with a curator in the department of prints and photographs, as it was called at the time, which is the department that I head now. Graduate school was not only important for getting the degree and learning about different aspects of art, but it is important for very practical reasons. You learn how to take on a new subject that you may know more about than anyone else and how to research it and turn your conclusions into a written form that you can share with others. You learn how to do original research, identify the specialists in the field who can help you, how to organize the material you have gathered and communicate your subject to others, and, very important, how to apply for funding. These are all things that I still do today in my present job.

Haidar: I started work quite soon after graduation having just arrived in the U.S. There are three approaches I have cultivated over time. One: History and literature are companions to Islamic art. I keep them close and work with specialists in those areas. Two: Appreciating aesthetics and artistic merit are skills that takes training and effort. I keep my eye sharp by looking widely and developing frameworks for critical comparison. Three: I express my enthusiasm for art and passion for my research, which has helped my professional activities, particularly communication.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for length and clarity.