From the Archive

Caryl M. Kline: A First Lady in Education

A profile from the Spring 1979 issue of The College Board Review reveals a trailblazing leader who, in the intervening decades, became unfairly lost to history

When Caryl Morse Kline died, at 87, in January 2002, she received an article-length obituary in her local paper, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, but few others took notice. There was no tribute in The New York Times. No mention in The Washington Post. The Harrisburg papers didn’t even notice, despite Kline’s place in state history. On April 20, 1977, Pennsylvania governor Milton J. Shapp appointed Kline Secretary of Education—the first woman to hold that position.

Kline’s term lasted only 20 months—Richard Thornburgh replaced her when he took office as governor—and when she left office she knew work was left incomplete. “One of the difficult parts of this job has been that people were in place when I came, and there was little opportunity to put a stamp on the department,” she told College Board Review editor Jack Arbolino. But in his profile of Kline, published in the Spring 1979 issue of the magazine, it’s clear that she left a mark on the state. And, indeed, her country.

Caryl Kline is one of the many, many public servants whose lives are immensely interesting but, when they drop out of public life, are easily forgotten. Arbolino’s profile is a wide-angle view of Kline’s experience, but it’s in the details where her story proves to be one that deserves a wider audience—especially today. Growing up in Wisconsin in the 1910s, she was immersed in politics and civics thanks to her college-educated mother. Kline recalled vibrant, vigorous discussions around the breakfast table—“[Our mother was] always the devil's advocate, and if the opinion was lopsided, she took the opposite point of view, which was simply great."—as well as her mother’s excitement at women finally getting the right to vote. In a story full of anecdotes, one of the most thrilling is her recollection of joining her mother in the voting booth and watching her cast her first, but not last, ballot. “I have never forgotten the lessons my parents taught: a democracy depends upon participation,” Kline said. “Surely the lesson from Mother was that a woman must exercise her political rights.”

Arbolino also tracks her life as a student activist in college, running for Syracuse city council in 1957 and, later, Congress, where she got an 11th-hour assist from “good friend” Jack Kennedy, then a senator; getting appointed by President Kennedy as a special ambassador to Sierra Leone, where she had previously consulted for the nation’s education department on its Women's Institute programs, which made her a “legend” there; and her brief stint leading Pennsylvania’s education department. Just when you think her career can’t take another larger-than-life turn, here comes another brush with history.

The profile is framed around her last day as Secretary of Education, which on its own makes for a powerful narrative device. (Congratulations across the decades, Mr. Arbolino, for earning that kind of access.) At times, it even feels cinematic. “After locking the door,” Arbolino writes, “she bobbed her head, and stood motionless for a moment beneath the two rows of formal photographs of all the men who before her had held the position of Secretary of Education of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.”

But the real power here is the lesson in civic involvement it imparts. Kline was a true believer in democracy—hard not to be with her kind of experience—and her thoughts on the relationship between officials and the people they serve are as resonant now—even more so—as they were in 1979, as the country pulled itself out of post-Watergate malaise: “I think it is exceedingly important that no public servant ever forgets that the strength of his or her office and the possibility of real accomplishment lie in the support of a participating citizenry and their elected representatives.”

Caryl Morse Kline is a great American with a great American story. We’re lucky to have this profile as a kind of monument to her experience—and, 20 years after her death, to keep her spirit alive.

College Board Review

Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Caryl M. Kline

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, like Albany, New York, and Trenton, New Jersey, is a capital city built on a river. It is a hub of railroads, like the others, and its population is dwindling. On the main street, too large to hide, is the common mark of downtown blight, a boarded-up movie house. The active movie in town also seems dead. On a weekday at 6:30 in the evening there is no movement under the marquee or in the lobby, and the blonde cashier who sits reading under glass seems cut from cardboard. A few doors away, similarly muted, is a massage parlor and adult bookstore. There is no looking in; the windows are curtained, but, like the movie house, though decorous in display, it is still unmistakable.

The city is clean and pleasant; it seems well run, safe, and even friendly. On the hill near the capitol is the education building. It is not unlike the many other structures in America that house departments of education: large, with ample bronze and marble, dreary and impressive at the same time. Its ceilings are high, its corridors wide and endless, the lavatories are spacious, clean, and cold; and the walls are colored with the bilious green so common to old schools and hospitals. Outside the office of the Secretary of Education, the walls are lined with large photographs of all the past chief state school officers of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, all stern-faced, all men.

At 5:30 on a cold dark morning in January, a quick, trim woman unlocked the front door of the education building. As the massive bronze door clanged shut behind her, she took a flashlight from her bag, bounced light down the corridor, then walked two flights of stairs to her office. The trim first invader of the dark and empty building was Caryl M. Kline, and although she did not know it then, she was nearing her last days of a 20-month tenure as Secretary of Education of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. She is the first woman ever to hold that job, and one of only eight women in the United States who in January 1979 were serving as chief state school officers.

The 5:30 start was not unusual. She worked alone at her desk until 7 o'clock, when her assistant joined her, and together the two women planned the flow of the day's work. At 8:05, she left the office to catch an 8:30 flight to Erie, there to begin an "outside" day that included three speeches (one at dinner), two college visits, one committee meeting, and an informal meeting with an old political friend. She got back home just before midnight.

On "inside" days, she would work in the office from 5:30 in the morning until about 11 o'clock every night. She approached her job the way she had always faced her responsibilities—with full commitment. Her tenure, as it turned out, was not full: appointed by Governor Milton J. Shapp on April 20, 1977, under Pennsylvania's newly elected governor, Richard L. Thornburgh, her term of office ended on January 15, 1979. About midway in her time in office this is how she described the job: "The responsibilities are great, for you are the image of education in the Commonwealth. I feel it is my task to be the advocate for public education at the basic and higher levels, but also to be the advocate for private education, for the quality of education in Pennsylvania is dependent upon its diversity—which assures us that whatever the interests and abilities of our citizens, there will be education available. One of the difficult parts of this job has been that people were in place when I came, and there was little opportunity to put a stamp on the department."

Despite her limited time in office, she made her mark by her talent, her courage, and, in the words of Arthur B. Sinkler, the chairman of the Board of State Colleges, by her "total immersion." He added, "I think she is the best-qualified person in the state of Pennsylvania to occupy the position of Secretary of Education." Deputy Commissioner for Basic Education Harry R. Gerlach says she was "a breath of fresh air—much loved throughout Pennsylvania and the country." The last observation is not exaggerated, but despite ability, dedication, and esteem, she left her office the day before the inauguration of the new Republican governor. She had been appointed by a Democrat. There was hope even after the election of Republican Richard Thornburgh that because of her qualifications and performance she might survive the customary political process. She did not.

Her development as an educational leader took unusual turns, as did her development as a woman. She is vigorous and direct; and although she is purposeful and energetic, she is not only nonthreatening and extremely likable, often she is somewhat disarming. On committees, for instance, she habitually rattles the lines of authority with candor and clear questions, but she is also able to pursue her points without being abrasive, and in the end, whether she makes her points or not, she is the committee member her colleagues want to sit with at lunch or dinner.

Illustration: Amy Rowen

She is an excellent speaker in a world in which many who reach the rostrum are less than electrifying. Not long ago at a national convention, she was the first presenter of a panel discussion on credit-by-examination. She spoke with clarity and feeling and without any strain or hesitation. She told no jokes, but she was humorous; and without scolding or exhorting she so moved her listeners that at the end of her talk there was an explosion of applause. The speaker who followed her was able to make his presentation without undue handicap only because he began by saying, "I hate to follow a wishy-washy speaker."

Caryl Morse Kline was never wishy-washy. In 1935, a state senator from Racine attacked the University of Wisconsin as a hotbed of "Communism, radicalism, and free love." The first volunteer for the defense of the University was Caryl Morse, a 20-year-old junior. After her appearance at the capitol, one newspaper headline read, "Co-Ed Claims University 99 and 44/100% Pure." Recalling the event, she says, "Can you imagine anyone so dumb? I went down there wearing white gloves, a white dress, and a white hat. What a ninny! Afterward my girlfriend said, ‘Caryl, why do you think we always take you home first?’” That kind of self-effacing recollection is more than vivid and engaging, it reveals in part the rocklike confidence of a person who, because she has known love all her life, does not have to seek it and is strong just where she stands. Her husband, a distinguished professor of geography at the University of Pittsburgh, says, "She combines strength and security. The Good Lord endowed Caryl with intelligence, energy, and a warm personality. To these talents she adds the essential ingredients of hard work and common sense." No longer does she appear all in white, but often she acts as if the outfit still fits and is hanging in her closet at the ready.

Strong Roots: A Family Education

Caryl Morse was the youngest of six children. They grew up on a farm in Verona, Wisconsin, and, during the school year, in the family's house in Madison, the state capitol. There was a span of 21 years between Mabel, the oldest child, and Caryl, the youngest. When Mabel was ready to marry, her father insisted that the wedding be postponed until the baby came. The delay he sought was to avoid the presumably disgraceful spectacle of a visibly pregnant mother of the bride. There is no record that Mrs. Morse argued against her husband's decision, but she might have, for she was an active, courageous woman not usually inhibited by artificial refinement.

Jessie White graduated from Downer College in Wisconsin in 1892 and married Wilbur Frank Morse, a farmer several years her senior. She used to tell her youngest child that she found it difficult to explain to herself the value of her college education. She was the organist in the village church, and she participated in whatever activities of the county were available, but in Caryl's words, "Mother needed more, so she became an entrepreneur in her own right. Every week she made over 50 pounds of butter and baked many loaves of bread. She also smoked meat and grew vegetables. Once a week she took her products to Madison, where she had regular customers among the faculty of the university and the officials of government. As a little girl I accompanied her regularly. Mother kept her income for the things that were important to her. She bought the piano, the organ, books, and the Model T that the twins wanted, but that my father would not condone; it was she who insisted on the reading materials being available so that we knew what was going on.

"I remember that August day when women got the vote, but I didn't really appreciate how much it meant to Mother. She took me with her to Longfellow School, and I still remember the smell of that gymnasium. I went into that little booth with the short, green curtain, and I stood there and watched her mark her ballot, fold it, and then proudly walk out and drop it in the ballot box. On our way home she told me how important this was and that now that she had the vote she would never fail to exercise it. As far as I know, she never missed a primary or a regular election from that day until her death in December 1938. I have never forgotten the lessons my parents taught: a democracy depends upon participation. Surely the lesson from Mother was that a woman must exercise her political rights.

"Our education was her responsibility. She was an accomplished pianist and organist as well as a painter. She thought that I must have a thorough training in such things, and so I began playing the piano early. But I really wanted to play the saxophone, so she took me to the Mansfield State College music store, but I often think she had an understanding with them, for they let me blow and blow on many saxophones. I just didn't have the vital capacity to do it, but I didn't lose my interest. When I was 11 years old, there was a saxophone player down at the theater. I went to see him. I just stayed and saw the show over and over. When Wayne, the brother closest in age to me who later became Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, had to come and get me it was after 9 p.m."

Caryl Kline believes that the family influence on her character was great. Her sister and brothers, so much older; her parents, wiser and more giving with the last late child—these circumstances she thinks gave her strength and confidence. "One of the important facets of growing up in our family was the wonderful conversation at the table—breakfast, lunch, or dinner. I always had breakfast with my father and mother, and even in the early morning we talked. Our mother was a remarkable woman, for we never knew what her political faith really was. She was always the devil's advocate, and if the opinion was lopsided, she took the opposite point of view, which was simply great. This kind of discussion and approach to issues was excellent training for the years to come."

College Board Review

Caryl Kline being sworn in as Pennsylvania's first female Secretary of Education, in 1977.

But even with her self-assurance, Caryl was aware as a child of sex discrimination. "In grade school, I asked the principal if I could take manual training. That really did it. Finally, however, she did let me take it, and I made a fish breadboard and a little lamp. I hate to think of the number of coping saws that were broken by me. Isn't it interesting that even without Title IX, back in the twenties grade school principals were permitting girls to do manual training and boys to learn home economics?" Even so, as she grew older she decided she "ought to be thinking of a way to make a living," and in college she majored in American history and public speaking, and later did graduate work in history, concentrating on the American Civil War. "My dreams—there were so many—were to be a minister, a lawyer, an historian, a politician. But I had learned to type in high school, and it was probably one of the best things I ever did, for it helped me earn my way through college after the crash of 1929."

In her senior year in college, she ran for president of the senior class and was elected. This was the first time that a woman had been elected to such an office. She recalls that it was great fun, "but I quickly learned that being elected to the office did not carry with it all the privileges that came to a young man elected to that office. For instance, the senior class president always sat on the Union Board, which governed the activities of the Student Union. It was known as the Men's Union Board. I appointed a senior class council that was truly representative of fraternity, nonfraternity, men, women, blacks, whites, and Jews. There was a great comment on campus about this, but in the end it was well accepted."

One of her most memorable professors was Frederick Roe, with whom, she recalls, she had a great difference over Algernon Charles Swinburne. "He made me sit one entire winter's afternoon from 1:30 until almost 5 o'clock while he read aloud to me from the poet's work." In a class discussion of Swinburne's in-love-with-death poem "The Garden of Persipone," she had objected to a line in the next-to-the-last stanza:

From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever God may be

That no life lives forever,

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.

The words, so contrary to her belief and understanding, so alien to her whole being, were "dead men rise up never." The professor worked all that afternoon to convince her that Swinburne was right: dead men never rise. But the poet's magic and the teacher's logic did not prevail. Her stand was based not on her belief in resurrection but in her conviction that no one ever really dies.

Caryl Kline continued to act on the strength of her convictions. "In my first graduate year, Philip LaFollette, son of Old Bob, was the governor of Wisconsin. He sought to load the Board of Regents with political appointees, contrary to the statutes of the state, and, therefore, I took the student body out on strike and led them in a march on the state capitol. We asked for the Governor. He came and addressed us. This was certainly an early example of student activism at Wisconsin, but it was neither destructive nor unruly. However, this action of mine did cost my brother the presidency of the university, for Mr. LaFollette had asked him to be the next president, and he was being interviewed for the job the very day I led the strike."

Wayne, later Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, was the brother who was hurt by Caryl's activism. Although he was 14 years older than Caryl, he was the closest to her. "My brother Wayne was in Madison attending high school when I was a little girl. I remember him very well, for he would pull me around on the sled or carry me in the basket of his bicycle. I remember clearly the Christmas when I was 3 years old (Christmas is my birthday). Wayne hitched ponies to a cutter and drove them from the line fence at the far end of the pond, up to the front of our farm home, where he stopped the cutter, and the ponies milled around leaving lots of hoof marks in the snow. Then he drove them on north to the other line fence and away. I thought Santa Claus had really been there and left all those good things. I even remember my presents. He was a marvelous brother and almost a second father. We remained close all his life, and I count it a great privilege to have known someone in public life of his integrity and courage."

Wayne Morse, the big brother who forged Santa's tracks in the snow for his 3-year-old sister, later became a distinguished United States senator. Before his election in 1944, he was a professor of law, then dean of the law school, at the University of Oregon. As a professor and a dean, he had a nationwide reputation as an outstanding labor arbitrator. Although he was twice reelected as a Republican, Senator Morse was consistently critical of the reactionary elements in his party. In 1952, he was guilty of Republican, if not political, heresy by refusing to support Dwight Eisenhower for the presidency. At the time, such a refusal was not only outrageous but also almost unbelievable. Still, Senator Morse was reelected, this time as an independent candidate. Subsequently he went the whole way, and formally joined the Democratic party. Twice more he was reelected, and he continued to express his political views courageously until he died in 1974.

College Board Review

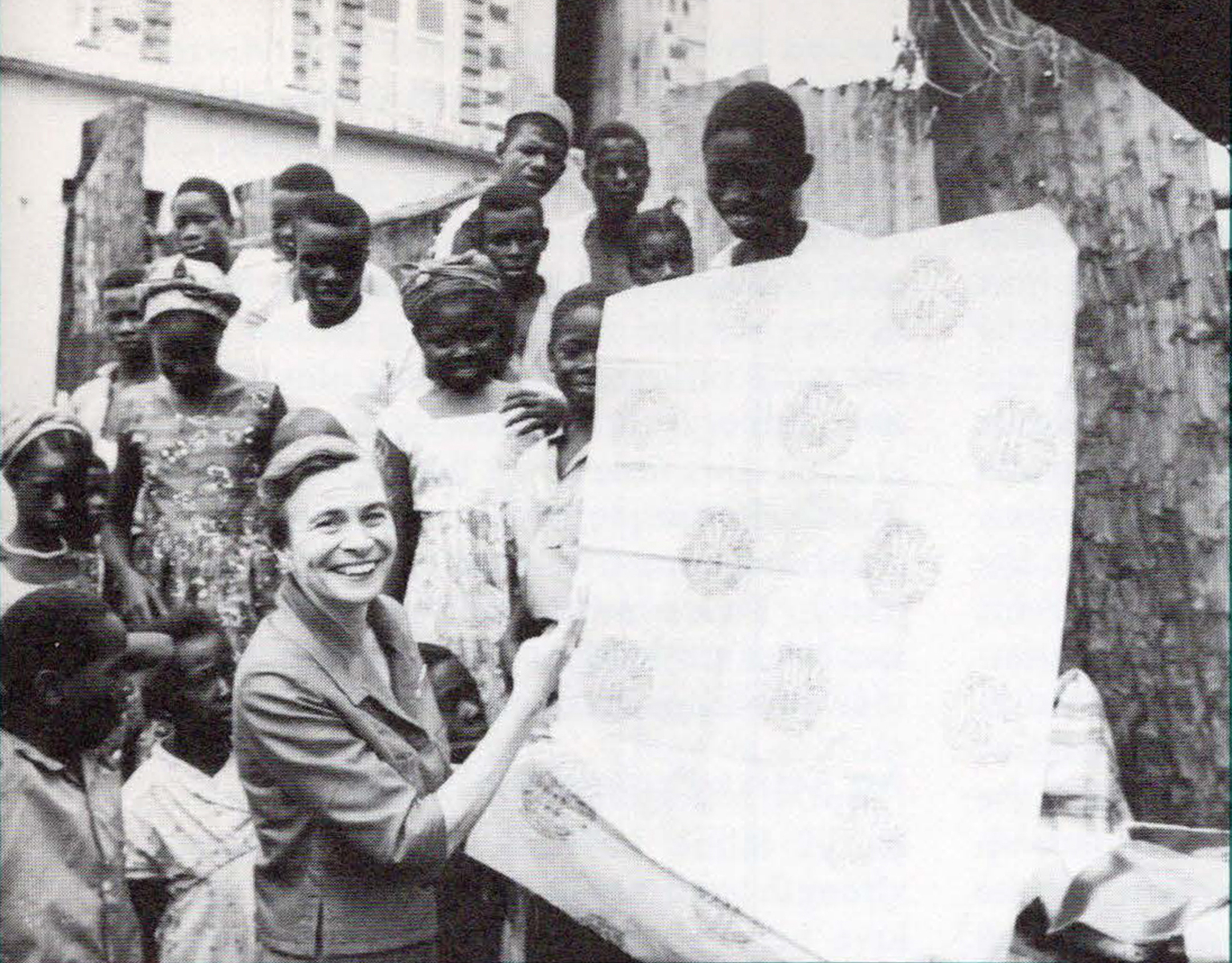

Caryl Kline with students in Sierra Leone, 1961.

An Active Professional Life

Caryl Kline has always drawn great strength and serenity from those who love her. About her husband she says, "While I was a graduate student at Wisconsin I married another graduate student. Hibberd Van Buren Kline, Jr. was working on his doctorate in geography. He has been very active in his professions, serving with OSS during the war as chief of the cartographic division, teaching at Syracuse University after the war until 1959, and then coming to the University of Pittsburgh as chairman of the department. For a time he was dean of the Graduate School of Social Sciences. He later returned to his chairmanship, where he is now serving. His special field has been Africa, and I have shared this interest. We have lived in Sierra Leone as a family. He has traveled and taught in many areas of Africa. We have had a very happy family life, for from the beginning he understood that I was a very active person, and he has helped me to participate in many different activities. In Syracuse in 1957, I ran for president of the City Council, and he worked very hard in my campaign. In 1958, when I ran for Congress, he was very much a part of the campaign. He wrote many of the releases, went to the rallies, and participated very fully, as did the children."

She is appreciative of her good fortune. "I could never have done what I have without Hibberd." He says of her, "Caryl has a legion of admirers and I am one of them. 'How is Caryl?' or 'Remember me to Caryl.' There is seldom a day in my life that someone doesn't speak to me not of Mrs. Kline, but of Caryl. And often it is someone I really don't know."

The Klines have two sons, Hibberd III, a lawyer in Missouri who raises beef cattle and is now studying animal husbandry, and Wayne Morse, who has a master's degree from Harvard, and who now works by choice, or avuncular destiny, in Oregon. Caryl Kline has also been, to cite just a few distinctions, a special ambassador to Sierra Leone, appointed by President Kennedy in 1961; an advisor on labor relations to the Queens' Board of Inquiry after the Sierra Leone riots of 1955; a candidate for Congress, 35th District of New York (she lost); and, to shorten a list that is long, a member of the Pittsburgh City Planning Commission.

Her professional and her personal lives have always been full. She makes light of her pace, but when pressed, offers two explanations: "I could never do what I do, or what I have done, without the complete cooperation and support of my husband. He has always assumed his share of responsibilities with the children. One of us was always with them. They are grown now, and they are fine. One time, when the two children were small, the three of them were traveling west to meet me (I had been campaigning with Wayne). They stopped to eat and were not immediately seated. The hostess said, 'Shall we wait for the mother?' 'No,' Hib said morosely, 'She left us.' They got royal treatment."

With all her fine forensic ability, she is a good listener, too. The basis of her confidence and her enormous capacity for work is only in part explained by the security she derives from her husband's strong approval and support, and her full acceptance of her responsibility in every job she's had to "let the people know." Advocacy and participation by the people are her canons of democracy. Her strength has other sources, old and deep: exceptional intelligence and energy; a strong spiritual and moral background that springs from family, church, and music; and a sustained sense of indignation at the position of women in America.

She responds to "Do you have any regrets?" by saying that she does. She is sorry that all the ways she might have gone were not really open to her. "The ministry, politics; I would have liked either or both. I would have liked the full chance to do anything I wanted. That wasn't possible for women when I was young." As she says this, she is truly sad. Her success and eminence in education and her pride in her marriage and family, particularly her husband, sons, mother, and brother, are separate from her sorrow over chances lost simply because she was a woman. Yet she has achieved: As the chief education officer of the state she was responsible for 5,623 schools—elementary, secondary, and combined elementary-secondary; 198 postsecondary degree-granting institutions, including state, community, and private colleges and universities; and a $2.5 billion budget divided roughly into $500 million for higher education and $2 billion for basic education.

In a world in which renaissance women are as valuable and scarce as renaissance men, movement, she thinks, is essential. She admits she was weary at the University of Pittsburgh, weary and ready to move. "I had done all I could there." Harrisburg was another matter. After 20 months, she was just getting hold: just getting established in Washington, just getting established with the state legislature, and working effectively with the departments of the state.

College Board Review

Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Caryl Kline addresses a 1978 meeting of the Pennsylvania State Education Association.

To the question "What's wrong with public education?" she has basic answers. "We parents want our children's lives to be easier. That hurts, and we don't make the demands for achievement and discipline that we should."

For teacher education she wants constructive criticism, and she faults liberal arts colleges no less than teachers' colleges in the retreat from responsibility for the proper preparation of teachers.

Her political experience showed in her hard stand toward the legislature. "I told them I would support no educational legislation unless the legislature supported it with money."

One of her hard lessons in politics was administered in 1958, when she and Hibberd were on the faculty at Syracuse University. She ran for Congress for the 35th District of New York. One week before election, the opposition launched a telephone campaign to the effect that her husband was about to divorce her. "It was just the dirtiest falsehood. Jack Kennedy called me and said, 'Caryl, I hear those Jebbies are giving you a hell of a time. Do you want me to help you?' I said yes, and he came up. He was a senator then. We campaigned together for a day, but I lost anyway—by 12,000 votes." When the news that she was leaving Syracuse came out, one headline read, "Merry Christmas, GOP, Mrs. Kline to Leave City." About JFK she recalls, "He was a good friend. I got to know him through Wayne. In 1961, he called and asked me to come talk. He said, 'We need you in Sierra Leone.'"

She had been to that country earlier as an adviser on labor relations and as consultant to Women's Institute Programs operated by the Sierra Leone Department of Public Education. It was for her work in the latter area that she is still regarded as a legend in that country. UNESCO still regards her as such for her untiring and remarkable efforts to open education to women.

Caryl Kline believes in work and planning, and she understands the urgency and desperation of women who at 40 and 50 years of age are trying to make a new start. She recommends that "every tentacle be out, every friend be approached, and every possible lead be followed." She knows the difficulty, and although the 50-year-old woman seeking a start in a profession often may be defeated, she is convinced that longer lives and different lifestyles are not only demanding more openings but are providing better prepared applicants to fill them. Her friend, Sister Jane Scully, president of Carlow College, says of her, "Caryl has been a pioneer in many ways, and an inspiration to women everywhere. Her ingenuity in promoting the cause of the older woman student, in defending her rights, and in facilitating her reentry into formal education in a large and complex university, was prodigious. When no one was speaking for the disenfranchised but hopeful would-be learners, Caryl spoke for them, clearly and eloquently.''

Looking Forward

January 15, 1979, Martin Luther King's birthday, was a holiday for the Department of Education of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It was also Caryl Kline's last day as Secretary of Education. Eight days before, her successor, with courtesy she appreciated, had called to inform her that he would assume the office on January 16, the day the new governor was to be inaugurated. Up to that moment, she had not known if she would survive the change of governors or, if not, who would replace her and when the transition would occur.

On her last day, the cavernous building was dark and almost empty. Occasionally the amplified noise of a closing door or a series of footsteps would resound and hang in the air. Her assistant, who had helped her pack, had left, and that job was almost done. She sat at a large conference table in her stately office discussing her thoughts in the last hours of her tenure. The paneled walls of the room, a sort of no-nonsense oak baronial, were bare, but they had been almost as unadorned before she had packed. Pictures and citations were never important to her. In contrast to many men of position who display every plaque and tablet their pasts can muster and their walls can hold, she seemed to abjure the practice of exhibiting her badges, not only because of natural modesty, but out of respect for the conservation of time and the elimination of distraction as well.

"I suppose even if this came later I would still feel I was just getting my hand on the department, but it's true. Twenty months wasn't enough time. I have a need to go home now, to go through a transition. It's funny going back to Pittsburgh. Twenty years ago when we decided to go there, I just sat down and cried. Winter, ice, snow, potholes and all, I cried to leave Syracuse. It was a one-party town for 104 years, and we were just about to crack it, but Hibberd had borne with me for a number of years, and I knew I just had to go with him. We left Syracuse in 1959.

"I don't want to go back to the University of Pittsburgh. I've done that, you know. I'll think a little and look around. I am interested in international education and many other things. I'd like to head a college, really lead it academically." When she was asked about the fundraising aspect of a college presidency, she replied, "That doesn't frighten me at all. Not for a moment. If your institution is first-rate, you can get support. I would welcome the chance—at the right place—to do both jobs."

Kathryn McDonald (Kline)

Caryl Kline in her office on her last day as Pennsylvania's Secretary of Education, alongside a group of headlines she garnered during her 20-month stint in office.

When asked if she had been a role model and if she had felt discrimination, she said, "I suppose I have been a model for some—at least I've frequently been told so recently, and in warm ways I appreciate. As for discrimination, yes, I've felt it. Mostly I never worried about it or warred against it, but occasionally it hit me clearly. Once, at Pitt, I didn't get an appointment because I was told 'It has a lot of traveling, and you wouldn't want to do that.' Why, what an arrogation! I wasn't asked; they just assumed."

She was asked what was the most difficult problem she faced, and she answered quickly. "You cannot break through a bureaucracy. It's the strongest thing there is. I could not find out why a simple print-order had to have three signatures." About political and bureaucratic changeovers, she says, "The turnover is sometimes frequent and traumatic. Now there is a new Secretary with a hoped-for tenure of at least four years, who must weld together his department and help some 1,000 people adapt to his educational philosophy. A Secretary coming in at the beginning of an administration should be able to choose his or her appointive personnel, have his or her own team, and be able to run the department smoothly in his or her chosen direction. The tragedy is that at the end of four years, the organization might be changed again. Is it any wonder that more and more people are turning again to the idea of more local control of basic education?" In some states, the governor appoints the Board, and the Board appoints the Secretary, with confirmation by the Senate. This procedure of designation puts the Secretary at least once-removed from political pressure and would seem to make the conduct of education more objective and less subject to pressure from the governor's office or the Senate or House Chamber. This is not to say that political pressure could not be brought, but it would not be so immediate.

Of her own approach to the politics of education, Caryl Kline says, "It is my strong feeling that the legislature was representative of the people and that my task was to keep a close rapport with the members, particularly those on the education committees. It is important for the legislature to know what your problems are in Washington or in the state and to be part of the solution. I think it is exceedingly important that no public servant ever forgets that the strength of his or her office and the possibility of real accomplishment lie in the support of a participating citizenry and their elected representatives. A civil-service bureaucracy can defeat you despite your own best instincts. You may know in your heart, for instance, that a school should not be built, and yet a bureau chief's interpretation of the rules, regulations, or statutes will give the green light. Regardless of who appoints the education officer, his or her task is a monumental one in this day of increasing federal encroachment, shrinking dollars, and shrinking enrollments, while the costs are ever increasing."

Throughout this discussion, though the building was closed and the offices were empty, there were interruptions. A security guard came in "just to see if everything was all right." Mrs. Kline addressed him by name and thanked him. One could not tell if he knew there was anything different about the occasion, for he did not say goodbye. An assistant division head came in to say thanks and goodbye. He concluded the parting with extra-hearty assurances of the many times they would meet again in the near future. There were several phone calls, nearly all of them about speaking assignments. She was able to direct the callers to the new Secretary, all except one, who persisted in trying to get her to commit her successor, not only to acceptance, but to a specific date. Finally, exasperated, but still courteous, she ended the conversation, hung up, and said, "Honestly, some people! And he's in the department. You'd think he would understand."

At last, she was ready to leave. She carried a purse, a heavy briefcase, and an open canvas bag full of papers. Outside the office, the far end of the corridor was lost in the darkness of the empty building. After locking the door, she bobbed her head, and stood motionless for a moment beneath the two rows of formal photographs of all the men who before her had held the position of Secretary of Education of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

"Do you still feel Swinburne and your professor were wrong?"

"That 'dead men rise up never'? Yes, I do. I just don't hold with that. There's a continuity of life and work. The love and confidence we learn and know, the things we do—through family, friends, and work—some of it is passed on."

She started to walk, and although she had always believed it, she said, as if she were just discovering a new truth that should comfort everyone, for it certainly pleased her: "I believe there is no finality to a life or a task."