Interview

Reunifying a House Divided Through Conversation

April Lawson Kornfield, Director of Debates of Braver Angels, sees curiosity and community as the solution to civic polarization

Alarmed by the growing mistrust between Republicans and Democrats in the aftermath of the 2016 election, a bipartisan group of Americans came together to create Braver Angels. The aim of the organization is to get people with opposing ideologies into the same room so that they can start conversations and learn from each other. It was an idealistic pitch in a divisive moment. But it resonated—and with some, like April Lawson Kornfield, it resonated deeply.

Several years ago, Kornfield was working as a researcher for the New York Times when she attended an event sponsored by Braver Angels. “There was something in the faces of the people I saw at the end of those workshops, where they were finding ways to talk to each other and truly listen,” Kornfield tells The Elective. “That just gave me so much hope for our country,” Kornfield said. “I felt like I had to learn more about Braver Angels and how they do this work.”

By 2018, Kornfield switched jobs to become Braver Angels’ director of debates and public discourse, helping bring the program’s unique style of discussion to community organizations and college classrooms all over the country. She believes people can draw closer together by leaning into conflict, honing their curiosity about someone else’s viewpoint so they can listen closely and understand their values and motivations. “Curiosity is the thing that will change your conversations and make them relationship-building rather than relationship-damaging,” she says.

Kornfield recently spoke with The Elective to explain the isolation and loneliness that drive vitriolic partisanship and dig into why she thinks there’s a hunger for a “different kind of political conversation.“

April Lawson Kornfield, Braver Angels

By many measures, we’re living through one of the most polarized times in American history. People don’t just disagree with people from differing ideologies; they can barely comprehend them. What drives that intense sense of tribalism?

That’s the million-dollar question, and it’s so important to find an answer if we’re going to give people a way back from this level of partisanship. Because you can’t take away partisanship identity without giving them something else to fill that need.

I think people are grasping for identity, for being part of something bigger. They’re seeking a moral system for making sense of the world. And what political identity does today is give you a team: “I’m with those guys! I’m part of something.” It becomes your whole identity.

There has been a lot of change in the last 50 to 75 years, and a lot of that change has taken away the things that traditionally helped people feel a strong sense of identity: ties to a particular place, ties to a church or a synagogue or another congregation, close ties to extended family. People’s jobs change all the time; they’re not in one job or even one career for 30 years the way they used to be. There are fewer things to give us a sense of coherence in our lives.

Do you think the pace of change is really that different now than in the past? I always think about my great grandmother, who was born before the invention of the car and lived to see the space shuttle. Is our era truly more dramatic than that?

The world has always changed fast. A Great Depression, a world war, the upheaval of the sixties. That’s a lot of change!

But, generally, people had structures and communities that were pretty constant. When you work in the same place for 30 years or live in the same town your whole life, your sense of who you are feels more consistent over time. People need consistency on some level. They need a North Star, a sense that they’re a coherent person with coherent beliefs.

If you get to choose your own identity continuously over time, if you get to select a large quantity of who you are, where you live, what your job is, then beliefs become more important. They become more central to your identity. And for many people, partisan, ideological politics is a core part of those beliefs.

In your essay last year about bridging the partisan divide, you focused a lot on building relationships. Why does that matter for lowering the temperature in our politics?

I think the decline in relationships and the rise of social isolation underlies all the major social problems we have right now, including polarization. To really understand where someone is coming from, you need to listen for their pain and hear where their pain points are. That’s almost always a big part of what’s driving extreme views.

We have freedom, but that doesn’t free us from our own needs. We still need people, we need identity, we need a North Star that helps our lives make sense. That’s why I think institutions are good for people—they give you a consistent set of relationships you walk through life with. When you’re part of a family or a congregation or a workplace, in long-term relationships with people that you didn’t necessarily choose, I think it just forces you to acknowledge the realities of being a person a little more. You can’t have a shallow perspective on addiction or mental health or what it means to struggle because you’ve been with real people through it all.

I watch people carefully. And in general, those who have other people in their lives are doing OK and those who don’t have other people—who are more isolated—aren’t doing OK. Without relationships, we really struggle. We grasp at abstract identities, at things that feel righteous.

What motivates people to break out of their partisan identity? Braver Angels has grown quickly, opening chapters across the country, so there’s clearly a demand for something different.

People get tired of being at war. They get tired of the fact that they not only disagree with their opponents but can’t even seem to understand people on the other side. They’re hungry for conversation, communication, reconciliation—for things that enable them to understand that these people on the other side aren’t aliens. Most people I know have lost or had some important relationships damaged by politics. So yes, people want something different, and they just don’t know how.

What we’re doing at Braver Angels is giving a lot of passionate people, who want to see something better, a way to make that real. It’s happening all over the country, and it’s mostly just giving people the ability to make their own communities better.

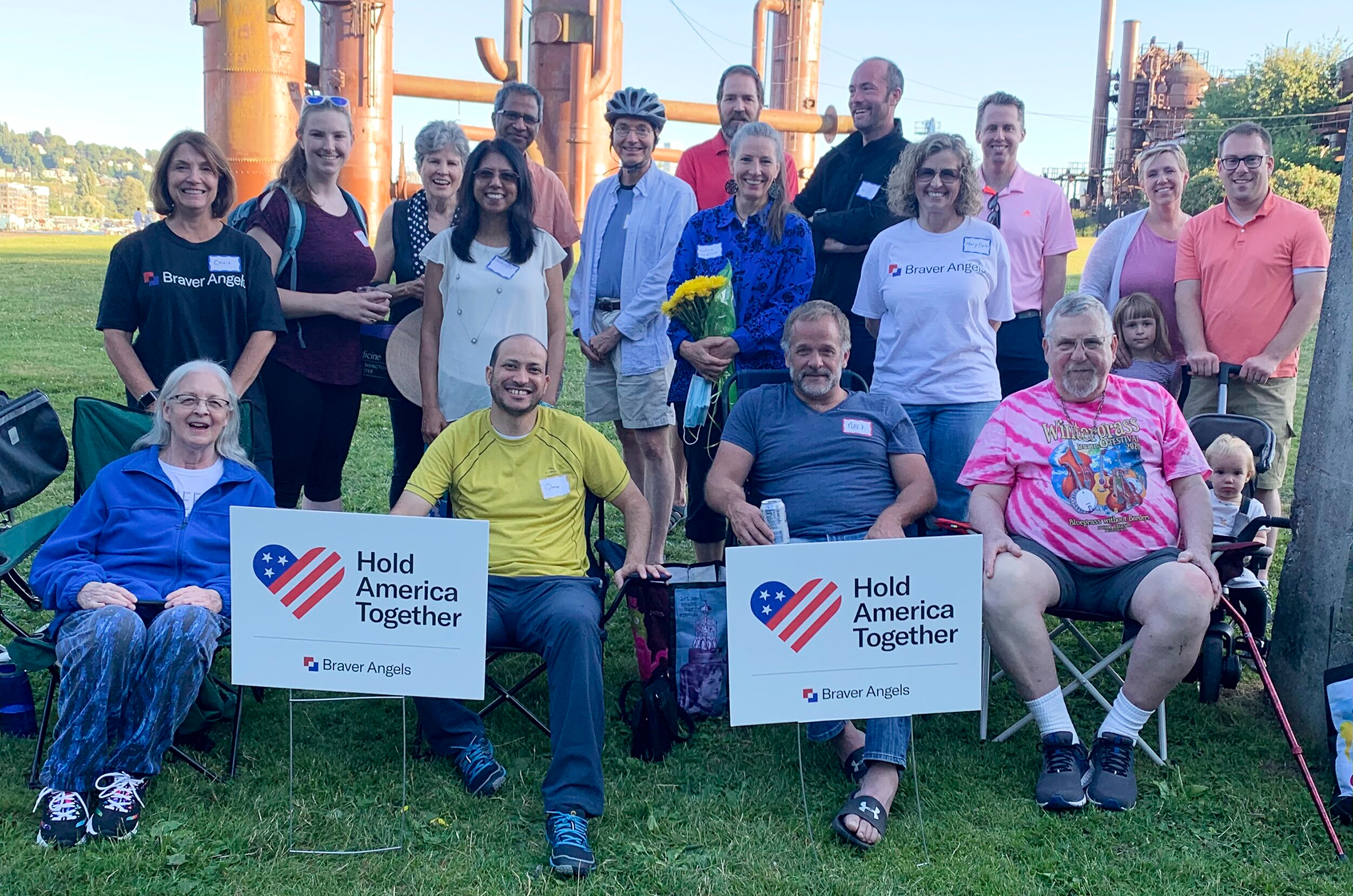

Braver Angels Washington State

Members of the Braver Angels Washington State Western alliance at a meet and greet in July 2021.

How do you make sure Braver Angels stays fair-minded? How do you keep an organization working to combat partisanship from sliding into partisanship?

We ensure that at every level of the organizational leadership, it’s 50-50 red-blue, 50-50 conservative-liberal. There’s just no way around that. People can have the best intentions in the world, but if you don’t have both sides at the table from the beginning it just won’t work. Even the subtleties of language are important. The word “dialogue,” for instance, codes blue. And you need people on both sides to be able to catch these things.

That’s fascinating about coded language—liberals and conservatives now hear completely different things in different words?

They do, and we pay very close attention to this. There are so many words that have acquired another layer of meaning, and you need to be attuned to that if you’re going to listen well.

On the left, words like “dialogue,” “diversity,” “unity,” “community conversation,” “difference,” and “empathy” imply that we’re all the same and that there are only certain ways it’s acceptable to be different. On the red side, words like “virtue,” “character,” “moral,” “patriotism,” or even “American” imply that the other person’s beliefs aren’t simply incorrect but fundamentally bad or corrupt.

At Braver Angels, we like the phrase “patriotic empathy.” It’s intentionally a red word and a blue word pushed together, so people pause and do a little bit of a double take. It makes them stop and think. It also captures a core thing about our organizational beliefs. If we want to heal the country, we have to start with individual relationships. It has to start with us; it has to start at home.

Has working with Braver Angels changed the way you interact with people in your own life, with your friends and family?

I think my work and family life are in dialogue. The thing that draws me to this work and sustains me is that I believe with my entire being that people on both sides have good hearts. And the reason I can know that with so much conviction is my family. I have profound disagreements with people in my family, but no one could convince me that they don’t have good hearts.

And the training from work does help with personal relationships. The practice of approaching tough conversations with curiosity rather than wanting to be correct or win an argument is really powerful. Curiosity is the thing that will change your conversations and make them relationship-building rather than relationship-damaging.

If you could bring a Braver Angels workshop to any group in the country, where would you have the biggest impact? Who needs to hear your message the most?

College students, for sure! I think a lot of kids walk onto a college campus and are looking for a way to be a great person. You have this spiritual sense of looking for a way to live in the world that is good, where you’re righteous and making the world better. And the narrative they hear now is primarily one about oppressors and victims. That can be good and righteous—it’s the narrative that defined that Civil Rights era—but it can also be destructive when it becomes an orthodoxy that gets applied to everything and everyone.

I think we want to restore colleges to their leadership position in teaching deliberative citizenship. Students need a sense of how to hold competing values in tension. You don’t deplatform and defeat your enemies, because the best leaders are in relationship with their opponents. Young people want to change the world, and I love that. But I want them to do it in a way that makes all of America better, not by trying to shut down half the country.

One of the big parts of my belief is that it’s easier to tear things down than build things up, and we need to encourage students to build and sustain institutions.

Braver Angels

A college student gives a speech to a room full of his peers at a Braver Angels campus debate event.

OK, so college students could be a core audience for Braver Angels. Who else?

Political people, of course! Most politicians hate this polarization stuff probably more than anyone, because it affects their day-to-day lives in terrible ways. We’ve started working with politicians and they’re saying, “Please help us!” This kind of partisan warfare is not what they went to Washington or Albany or Topeka to do. This isn’t why they joined the city council or the school board. Giving them the ability to set their communities up for a real conversation, instead of a shouting match, could make a real difference.

I also want to see us do a better job of reaching truly disaffected people. On both the left and right, there is a profound sense of alienation. People don’t believe they are part of this thing called America, that it’s for them. They need to feel like they’re not just a spectator, but a real part of it. If we could get those voices reintegrated into the healthy, sometimes intense processes of our democracy, instead of leaving it to the extremes, I think it would be healthier for all of us.

For students wondering how they can follow a similar path, what’s the secret? How did you get into this field?

It sounds cliché, but don’t give up. I ended up working for Braver Angels after researching and writing about them while I was working with David Brooks at the New York Times. I sought him out because I felt like he was naming truths that I felt in my gut, that his writing was picking up something very deep in my life. I said, “I want to work for that guy!” I went to an event he was having on campus and got his email address. I followed up. I sent letters. He finally had coffee with me, and a couple years later, he was hiring somebody, and it went from there.

If you see something that resonates with you, chase it. You can get through many more doors than you think if you are persistent and really sincere about why you love whatever it is you’re trying to do.

I think we need the things that young people love. We need you to be that thing you love and care about. I don’t want you to do something just because you think it's the safe or sensible option. I want you to add that other thing to the world, that thing you feel in your gut. And you can—you just need to stick it out.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.