From the Archive

Brown v. Board of Education at Fifty: A Personal Perspective

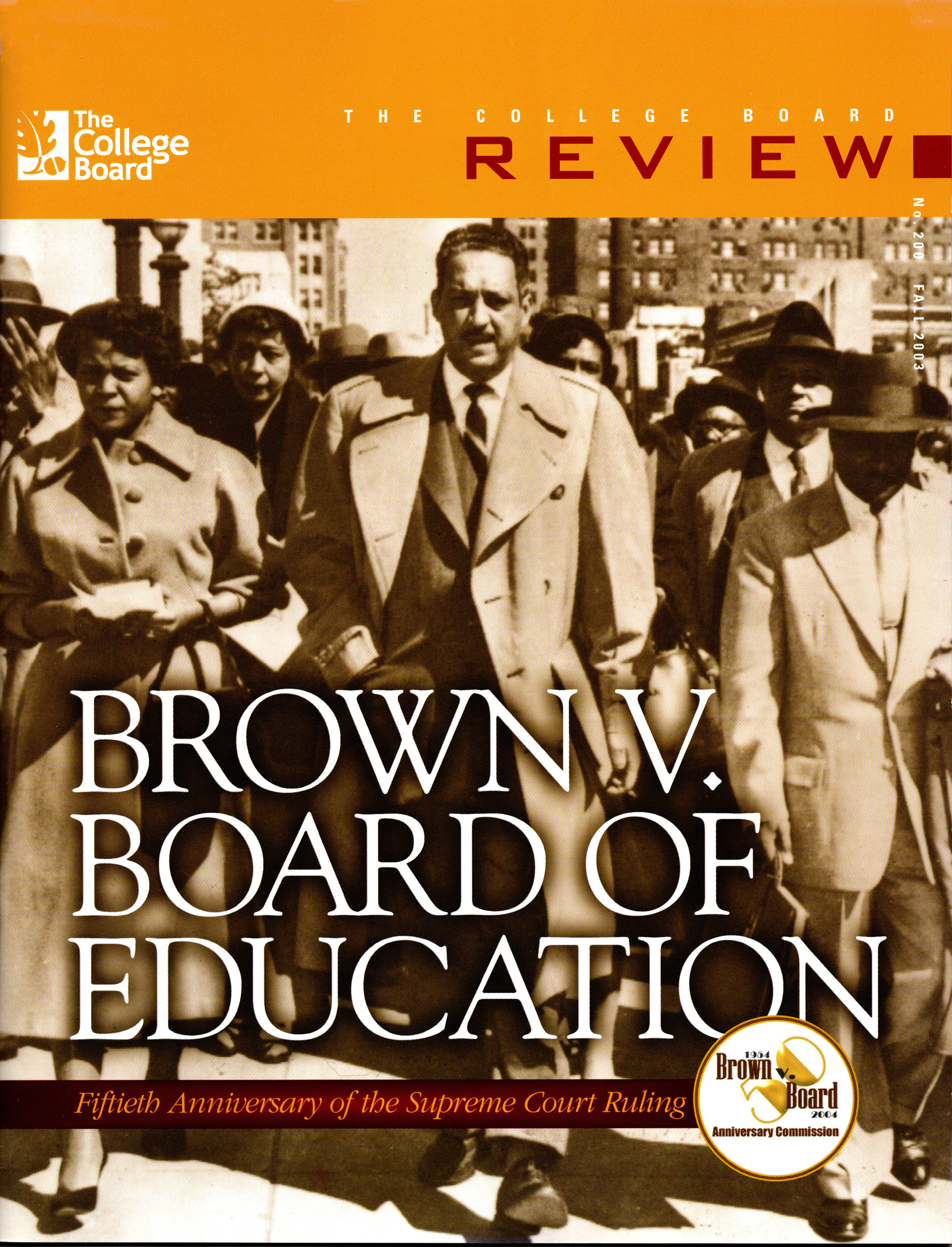

The College Board Review marked the anniversary of the seminal school desegregation Supreme Court ruling in its Fall 2003 issue with an essay from Oliver Brown’s daughter

If there were a Mt. Rushmore of Supreme Court decisions, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka would surely be on it. (Marbury v. Madison, New York Times Company v. Sullivan, and Roe v. Wade would be up there, too.) The landmark unanimous decision, delivered in 1954 by Chief Justice Earl Warren, desegregated America’s public schools by finding the principle of “separate but equal,” outlined in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, unconstitutional. Brown v. Board was a major victory for civil rights and equality in education, and it’s the rare Supreme Court case so consequential that it has entered the firmament of everyday American conversation.

In the Fall 2003 issue of The College Board Review, which was dedicated to the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board, Cheryl Brown Henderson contributed an essay that added a personal dimension to the decision. Her father, Oliver, is the case’s namesake (an accident of history, and possibly misogyny, she writes), and at the time her piece was published she was executive director of the Brown Foundation in Topeka, Kansas. She comes at the case, and its impact, from a unique perspective: She was in the room when her mother heard the news of the Court’s decision; she grew up in its immediate aftermath and witnessed in real-time its impacts (and failures); and she has dedicated her life to helping the nation grapple with and interpret its legacy.

“Although the legal battle was won many years ago, the goal of equal educational opportunity for our children remains elusive,” she writes. “A system of de facto segregation still exists in many cities and towns across the country, and great inequities still exist in the financing of our schools and in the availability of qualified teachers to teach in those schools.” That was a hard, but real, truth in 2003, and in the years since it has become an even more urgent cause of concern. “Separate but equal” may no longer rule the land, but uneven distribution of public school funding, resources, and opportunities have helped hasten the resegregation of too many districts. (The second episode of the New York Times’ excellent Nice White Parents podcast takes a long look at the long tradition of school segregation in New York City.)

The challenge of ensuring all children have equal access to quality access is large. But it has always been. And in Brown Henderson’s essay is a call to action—one that America should take up as we approach the 75th anniversary of Brown v. Board: “as those who went before us, when we hear history's call, we too will have the courage to stand up and answer.”

The Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas

Rev. Oliver Brown, whose became the namesake—quite by accident—of the Brown v. Board of Education case.

On May 17, 1954, around midday, my mother was listening to the radio while she did the ironing at our home in Topeka, Kansas. As she worked, she heard the news report come on the air: the U.S. Supreme Court had rendered a unanimous decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, effectively outlawing racial segregation in public schools across the nation.

The words of Chief Justice Earl Warren, words that reverberate to this day, were read aloud for the first time: "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

It was one of the most important Supreme Court decisions of the twentieth century, one that would change the course of American history. The case bore my father's name, and one day it would have a profound effect on me, my family, and the entire country. But on that day in Topeka, strange as it may seem, it was not big news. My mother simply returned to her ironing. And my father, Oliver Brown, the lead plaintiff in the case and a welder for the Santa Fe Railroad and pastor of St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church, didn't even hear the news until my mother told him when he returned home from work that evening. How could it be that such a momentous decision was not greeted with raucous celebration?

The answer lies in the difficult and complicated history that led up to the court case and some of the myths that have emerged since the court's decision. As head of a foundation whose mission is to educate the public about the significance of the Brown decision, inevitably this has meant addressing some of these myths. As we approach the fiftieth anniversary of the Brown decision, it therefore is fitting that I take stock of this history and offer a few thoughts about the decision's importance for our times. These observations are from someone who carries with her not only the name of this famous decision but part of its personal legacy, too.

Thomas J. O'Halloran/U.S. News & World Report Magazine/Library of Congress

Photograph of lawyer Thurgood Marshall, published by U.S. News & World Report Magazine on September 17, 1957.

A Crucial Turning Point

The truth is that it took years before the full effect of the Brown decision was felt by the nation—and my family. From the perspective of 2003, it is astonishing to see how farreaching it really was. First, as hard as it is to imagine today, there was a time in this country—and in my lifetime—when racial segregation was sanctioned by law. The Brown decision was the beginning of the end of that shameful period. In addition to overturning laws that allowed segregated schools in Kansas and 20 other states, it also struck down the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision, which had given us the infamous doctrine of "separate but equal." But perhaps most important of all, it reaffirmed that all of the citizens of this country were entitled to the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Scholars and historians also mark the case as a crucial turning point in our country, opening up a period of social conscience, equity, and justice that had not been seen since the political underpinnings of the Civil War. Brown served as a catalyst for the civil rights movement and set the precedent for landmark legislation of that era and beyond, extraordinary legislative milestones such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the 1972 Education Amendments Act giving us Title IX, among others. Ultimately, the decision paved the way to equal rights for Americans of every color, for women, for the disabled, and for older Americans.

Sadly, my father died in 1961 and he never lived to see any of this. Had he lived, I am sure he would have been amazed to see what the case ultimately accomplished and how history had made him an icon, albeit an accidental one. For contrary to some of the myths surrounding the decision, my father was not the promulgator of the Brown v. Board case. He and parents from 12 other families had been recruited by the local chapter of the NAACP to challenge the law that upheld segregation in the Topeka Elementary schools. In all probability, his name came first on the list of plaintiffs—and therefore secured for him a lasting place in history—because he was the only man among the plaintiffs, perhaps a reflection of the gender politics of the day.

What all 13 plaintiffs shared, however, was a basic fact of life. Although they lived four or five blocks away from the nearest public elementary school, the school was for White children only. Therefore, some children had to be bused 30 or 40 blocks to a segregated Black school. Although Kansas had a relatively progressive history in terms of race relations, the state was dragging its feet in integrating the elementary schools (all other schools were integrated at that time). To these 13 parents it made not only "civil rights sense" but common sense to end the practice.

A Story of Personal Sacrifice

Of course the case ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court, but what many people don't know is that it was combined with four other school segregation cases from Delaware, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, and Virginia. It is also important to remember that although the participants in Kansas generally did not suffer dire consequences as a result of their school enrollment attempts, the same could not be said about the plaintiffs in the other cases. For many of them, their willingness to take a stand cost them dearly.

For example, Reverend J. A. DeLaine, who organized Briggs v. Elliott, the South Carolina case, had to flee his house in the middle of the night in fear for his life. His home was later burned to the ground. Annie Gibson, who was a plaintiff in Briggs, lost her job as a maid in a motel and her husband was forced off the land he had farmed for over 50 years. In an interview for an oral history project conducted for the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, she said that if the Black schools had desks, she never would have signed the petition that demanded better educational facilities.1 These ordinary people made extraordinary sacrifices and were the true foot soldiers in the revolution.

There are many other people who should be recognized for their valiant efforts in the cause of school desegregation and the Brown v. Board story in particular, although I don't have the space to do them justice here. Thurgood Marshall, the lead attorney for the NAACP in Brown v. Board, who would one day distinguish himself as a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, is perhaps the most famous name associated with the case. It is also worth remembering another man, Charles Hamilton Houston, whose role in the fight for school desegregation is less well known but in many ways is just as important.

Houston was a man of remarkable conviction and accomplishment, including becoming the first African American editor of the Harvard Law Review. He served as dean of Howard University Law School, making it a training ground for generations of African American civil rights lawyers. As the special counsel to the NAACP from the 1930s through 1950, Houston was instrumental in crafting the legal strategy that targeted inequality in education, a strategy that resulted in several successful legal precedents that eventually led to the Brown decision. Although he had to step down from his position for health reasons, Houston remained an important adviser to his successor, Thurgood Marshall.

Vieilles Annonces/Flickr

The May 21, 1964, cover of Jet Magazine featuring students involved in the Brown v. Board of Education case. The story inside the magazine was published with the headline "5 Pioneers Find Neither Fame Nor Fortune After Case."

Learning the Lessons of History

Observing the Brown Foundation's activities over the years—whether it was the lawyers handling the cases, community activists organizing petitions, or the many families who participated as plaintiffs—I have learned that what we do to remember and recognize the many actors in the school desegregation drama is an important part of the effort to recover the true history and meaning of the events leading up to the Brown decision. Uncovering the truth of the past is also to discover its genuine lessons. But what are those lessons for our times?

I am a teacher by training; I believe deeply in the value of education and providing all of our children with a high-quality education. I believe that making good schools available to all our children is essential to create an educated citizenry, and an educated citizenry is a prerequisite for a healthy democracy. At the very least, this is what the school desegregation fight was all about. The parents and children who participated in these cases believed just as deeply in the value of education and the justice of their cause. They had the courage of their convictions and were willing to stand up for their rights and the rights of future generations.

Unfortunately, although the legal battle was won many years ago, the goal of equal educational opportunity for our children remains elusive. A system of de facto segregation still exists in many cities and towns across the country, and great inequities still exist in the financing of our schools and in the availability of qualified teachers to teach in those schools. So the educational agenda of the civil rights movement remains unfinished. Changing this will require nothing short of a sustained national commitment and the hard work of many people who are willing to stand up and make their voices heard.

Despite what some people may think, our system of government works exactly the way it was explained to us in civics class so many years ago: The structure is there, but as citizens, we have to make it work. That is one of the other important lessons I learned from researching the history of the Brown decision and from our foundation's work with the U.S. Congress and the National Parks Service to create a national historic site in Topeka to commemorate the decision.

Over the years, the story of Brown v. Board of Education is for my family and me where the personal intersects with the public in strange and complicated ways. Because the case was named for my father, our family was often the first stop for people searching for information and answers about the Brown decision. Eventually this prompted my mother and sisters and me to become students of the decision and spurred us to help maintain its legacy. In the end, I discovered how fitting it was that my father became the accidental icon of the school desegregation story. For me, he came to represent the quiet action of hundreds of ordinary people who heard and answered the call of history.

So as I think about the fiftieth anniversary of Brown, this is what I would wish for all of us: that as those who went before us, when we hear history's call, we too will have the courage to stand up and answer.

Endnote:

1. Jean Van Defender, "Capturing Forgotten Moments in Civil Rights History," The Brown Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 1999)