In Our Feeds

Clubhouse Crashers, Pizzabots, and Family Dynasties: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From a youth sports elegy to influencer culture anthropology, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Antonio Masiello/Getty Images

People get their pizza from Mr. Go Pizza vending machine, on June 7, 2021, in Rome, Italy. Mr. Go Pizza is the first automatic pizza vending machine, open 24/7, which is capable of kneading, seasoning and cooking the pizza in three minutes.

One Large Pie With Extra Snickers

If you’re going to build a pizza ATM, college campuses would seem the ideal place to put it. And sure enough, the last few years have brought a handful of pizza-dispensing robots to Ohio State, Xavier, and the University of North Florida. (College students are not known for discerning palates or traditional dining hours.) But now the pizzabots are taking on a more culturally fraught market: the heart of Rome. An Italian medical device entrepreneur built a machine that cooks fresh pizza—from kneading the dough to melting the four-cheese topping—in about three minutes. “Food journalists and bloggers have mainly turned up their noses, with one comparing the vending machine’s creation to a pizza she’d eaten in a rundown area of the Ecuadorian Amazon while on a mission with Oxfam,” reports the New York Times. But foodies aren’t the target market. The pizzabot will be available all night long, when the city’s traditional pizzerias are closed and hungry cab drivers, maintenance workers, and—yes—college students might appreciate a hot pie.

The Times also points out that Domino’s managed to build a thriving business in Italy, so perhaps the pizza snobbery doesn’t run quite as deep as Italians would like us all to believe. Neither Domino’s nor the pizza ATM are likely to earn a spot on UNESCO’s official Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, as Neapolitan-style pizza did in 2017. But whenever our artificially intelligent overlords finally conquer the planet and start keeping their own lists of the Intangible Heritage of Algorithms, I imagine the first Roman pizzabot will make the cut. —Stefanie Sanford

YouTube

This comes from a video titled "Breaking Into Not a Content House," which... ¯\_(°ペ)_/¯

Clubhouse WTF

Harper’s is a fussy magazine, and I mean that as a compliment. Old-school cultural snobbery is kind of their brand, and they lean contrarian on the major artistic and social questions of the day. So when Harper’s dispatched a beanie-wearing English professor from a small college to profile the TikToking denizens of ClubHouse FTB, a mansion full of online “influencers,” the editors knew exactly what they were doing. Professor Barret Swanson sits poolside and observes the made-for-social-media insanity of the “collab” house, where a half-dozen college-age dudes spend their days brainstorming and performing very non-college activities. “For the past thirteen years, I’ve taught a course called Living in the Digital Age, which mobilizes the techniques of the humanities—critical thinking, moral contemplation, and information literacy—to interrogate the version of personhood that is being propagated by these social networks,” Swanson writes. “It increasingly feels like a Sisyphean task, given that I have them for three hours a week and the rest of the time they are marinating in the jacuzzi of personalized algorithms.”

At Clubhouse FTB, while the kids marinate in the actual jacuzzi, Swanson contemplates what it means for a generation to grow up buffeted by the pressures of personal branding. The professional influencers may be the most extreme example, but Swanson sees the branded future coming for all of us. “These kids were very young when their parents gave them iPhones and tablets—they’ve never known a self that wasn’t subject to anonymous virtual observation,” he writes. “We’ve become cheerfully indentured to the idea that our worth as individuals isn’t our personal integrity or sense of virtue, but our ability to advertise our relevance on the platforms of multinational tech corporations.” I have never seen a TikTok video—I read my Harper’s content in print, delivered by a mail truck—and Swanson’s melancholy musings felt like a perfect measure of the generational chasm between those of us who grew up without smartphones and today’s screen-soaked young people. I don’t envy the teachers and college professors trying to connect across that divide. —Eric Johnson

Rob Carr/Getty Images

Michael Gaines #15 of the West team celebrates with third base coach Doug Holman during the sixth inning of the West's 12-1 win over the Westport, CT team in the United States Championship game on August 24, 2013 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

Littler League Baseball

Like a lot of geriatric millennial (ugh) men, I played baseball as a kid. And like a lot of geriatric millennial men, I wasn't good enough to make it beyond the first year of Little League, let alone a spot on the 26-man roster. But it didn't matter because, more or less, I had fun playing (hit one home run, an inside-the-parker at that!) and got to be part of a game I loved. I got a uniform I cherished, a glove I hauled with me to pro games, and my face on a baseball card during team photo day. It was great! And it's a major reason I'm still a baseball fan today. But that experience is a universe away from what kids experience now—if they play baseball or, indeed, any organized sport. As Nicholas Dawidoff documents for The New Yorker, a game that used to have space for players from all sorts of social backgrounds who honed their skills playing stickball, on successful local teams, and in ragtag pickup leagues has now, like so much of our culture, cleaved into a competition on a wildly uneven playing field, where the haves really have and the have nots are left to pick through the dugout scraps. The culprit: travel leagues, where parents pay big bucks for the privilege of washed-out semi-pros grooming their kids for college scholarships and, ideally, the pros. "Travel sports seem of our time, not simply in their aspirational striving to purchase an edge, to get ahead, but in the way they create inequity and separation within the culture," Dawidoff writes. "Most people don’t have thousands of dollars to invest season after season in a nine-year-old third baseman."

Even if you don't have kids or have never played sports, Dawidoff's piece is worth a read. He frames it around the draft for his local Little League, where he's a coach and his son's a player, but then uses the league's hard luck—"During years past, Hamden had filled two complete and abundantly rostered leagues. Now we were drafting to field four teams in one league."—to get at larger issues roiling America: segregation by race and class, opportunity hoarding, the slow death of institutions. And using Little League to tell this story is a clever choice; it also allows Dawidoff to Trojan horse a surgical swipe at both entitlement culture and the cult of ambition. "For generations of Americans, it’s been a national rite of passage, an early lesson in mortality: the revelation that you won’t, after all, be a major-leaguer," he writes. "Typically, there was self-discovery in this... With travel sports, though, it could feel less like the way it goes for almost all of us than a personal inadequacy. If, after all that preparation, you failed to win a scholarship to play Division I college ball, it was your fault." Of course that's a ridiculous attitude for anyone to take when it comes to baseball. But maybe the worst impact of a travel league? It's "more likely to ruin the pleasure in baseball for a kid." Make Baseball Fun Again! —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Michael Campanella/Getty Images

You don't need to be part of an actual dynasty, like the Swedish royal family, seen here celebrating King Carl XVI Gustaf's 72nd birthday in 2018, to feel the impact of “Dynastic human capital." At least, that's what researchers *want* you to believe.

Harder Than IKEA Furniture to Assemble

Where you end up in life depends not just on the fortunes of your immediate family, but on your extended network of aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. That’s one of the basic conclusions of a large new study from a team of international researchers who analyzed four generations of data from the entire population of Sweden. “Dynastic human capital” is a powerful force, they found, and ancestral family status accounts for a greater share of individual life outcomes than previously realized.

Politicians and social scientists care a lot about social mobility. In theory, we want a society where people are able to move up or down based on their own effort, and we generally think that should be reflected in high levels of mobility. But it’s both difficult to define—Does it mean more money? More education? Longer and healthier life?—and wickedly difficult to influence through public policy. What the Swedish research suggests is that we’re up against some very persistent, very deep-rooted forces when we try to use schools or housing policy or tax incentives or scholarships to make a large-scale difference in people’s life trajectories. That’s not to say that we should give up, but simply to acknowledge that privilege compounds, and disadvantage cascades, across multiple generations. Everyone who works in public policy should have a little humility for what they’re up against. —Eric Johnson

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

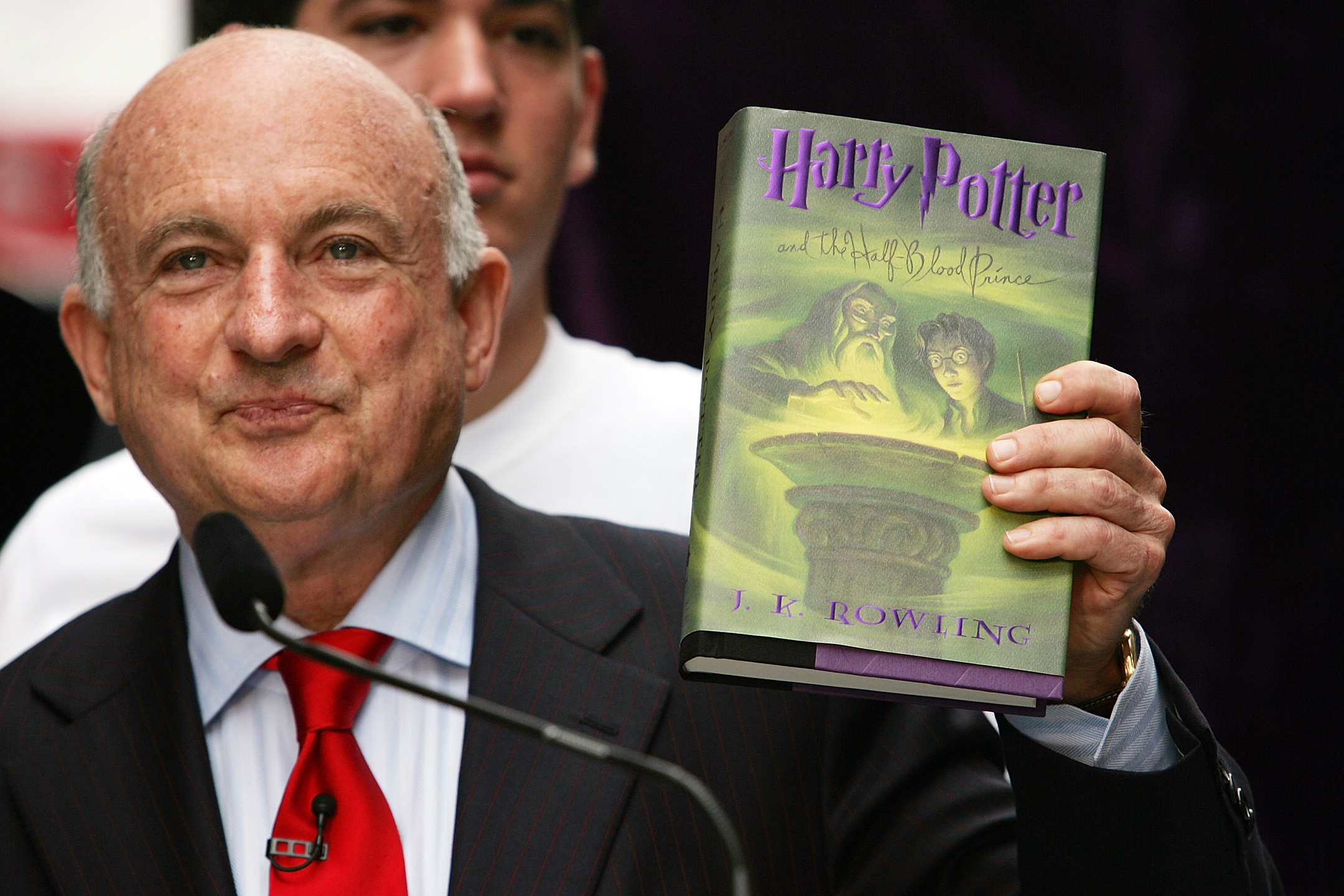

Scholastic CEO Dick Robinson holds the first author-signed American-edition of author J.K. Rowling's new book, 'Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince' July 15, 2005.

Read Every Day, Led a Better Life

Harry Potter. The Hunger Games. The Magic School Bus. Goosebumps. Captain Underpants. These are book series that have defined generations of readers, and they have been foundational in inviting countless kids into the magic of books—and the power of imagination and agency imbued in them. And while those series are all the products of individual authors, it's not hyperbole to say we wouldn't have them without Dick Robinson, who died last Saturday at 84. As the head of Scholastic for decades, Robinson helped turn a children's book and kids magazines publisher into a global cultural powerhouse. His father, Maurice, founded Scholastic in 1920 in Pittsburgh, with its first product a magazine for young readers; 43 years later it published Clifford the Big Red Dog, created by Norman Bridwell, a cornerstone of every young reader's library. Dick Robinson joined Scholastic as an associate editor in 1962, became president in 1974, and named CEO in 1982, a role he held until his death nearly 40 years later.

Harry Potter is perhaps Robinson's headline legacy, but his importance to publishing and literacy is hard to overstate. "Publishing the Harry Potter books has changed the company and made it more visible,” Robinson told The New York Times in 2005. “But what everybody feels the most about Harry Potter is that it brought kids to the reading process who had never been readers.” His commitment is something I experienced up close during my time at Scholastic, from 2008-2013. I joined the company to be an associate editor on Scholastic News Online, a daily news website for kids, and I left as the Editorial Director of the Scholastic News Kids Press Corps (with a layoff in the middle there somewhere). It was a great time to be in the building: the Harry Potter books concluded and the movies heated up; The Hunger Games was published, optioned, and made into its own multi-billion-dollar franchise. (My desk was near the room where the first movie was plotted out. Exciting!) Thanks to my work with the Kid Reporters, I met (and prepared the kids to interview) Bridwell, R.L. Stine, Taylor Swift, Steven Spielberg, President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, Meryl Streep, John Baldessari, One Direction, Guillermo del Toro, Martin Sheen, Andrew Garfield, Shimon Peres, and so many other authors, actors, filmmakers, athletes, politicians, and leaders. These were transformative experiences for the 100 or so 10-14-year-olds I collaborated with in my five years at Scholastic. And my time at Scholastic transformed me. (I also suited up as Clifford once or twice, which was… fun? Stories for another day.)

None of that would have happened without Dick Robinson. In 2009, the Kid Reporter program was near death, the victim of petty squabbling and dumb political in-fighting within Scholastic's magazine group. I can count on one hand the number of people who wanted to save it—Robinson was one of them, and arguably the most important. It is because of him that so many young people had a chance to put a lot of good into the world through their reporting—on their communities, on the nation, on culture, on the world—and that so many young people had an opportunity to get quality journalism written and crafted by their peers. “We are dealing with issues like global warming, racial inequality in a way that doesn’t polarize the issue but gives points of views on both sides and is a balanced neutral position but not in a sense of being bland,” Robinson told the Associated Press in 2020. “Here are the arguments on the other. Here is what people are saying. Here are questions you can ask to formulate your own view.” That was true in my time, too. And to think that that was just a small component—and often an invisible one—of his life's work.

Dick Robinson was a champion of literacy, reading, and education. But he was also an ally of good, objective journalism that can objectively do good in the world. He seemed like a permanent fixture of Scholastic when I was there—we often wondered what Scholastic would be like without him. We're about to find out. But his legacy, while complicated, is unimpeachable. And let me add my voice to the chorus of authors, educators, parents, and kids to say thanks, Dick, for the opportunity you gave me—but, more importantly, to all the kids who were able to put on their journalist's cap. —Dante A. Ciampaglia