In Our Feeds

Dodo Brains, Saturn’s Ring Cycle, and Busting Caesar: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From job placement to natural displacement, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Daniel Eskridge/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images

An outtake* from the prehistoric prelude to the new "Jurassic World" movie, which would've made the dodo a Hollywood star. Alas, it has been made extinct a second time. [*not really, though it would be awesome to see dodos in a "Jurassic" film!]

Science, Uh, Finds a Way

Jurassic Park, among other things, is a cautionary tale about the dangers of resurrecting extinct animals, with the book and movie arriving long before the technology to actually pull it off. Well, that technology is here—and the species chosen for resurrection is far less dangerous than a velociraptor. Researchers working with a skeleton housed at the Natural History Museum of Copenhagen, recently extracted the complete DNA sequence of the dodo. That means the three-foot-tall flightless bird that went extinct on its home island of Mauritius in the 17th century could one day harmlessly walk the earth once more. (Its fearlessness of humans earned it its name, the Portuguese word for “fool.”) But bringing the dodo into the 21st century will take some doing. “If I have a cell and it's living in a dish in the lab and I edit it so that it has a bit of dodo DNA, how do I then transform that cell into a whole living, breathing, actual animal?” lead researcher and UC Santa Cruz professor Beth Shapiro said in a webinar. “The way we can do this is to clone it, the same approach that was used to create Dolly the sheep, but we don't know how to do that with birds because of the intricacies of their reproductive pathways.”

Shapiro added that mammals have a simpler de-extinction process than birds like the dodo and passenger pigeon. That has led to hope for a fast-tracked earthly reappearance of four legged extinct species like Australia’s thylacine and the iconic wooly mammoth. Harvard geneticist George Church’s company Colossal aims to imprint mammoth DNA on the Asian elephant to create a hybrid that serves the ecological function in the frozen tundra as the ancient original. Others, like University of Copenhagen geneticist Tom Gilbert, are skeptical of how genetically close such a “mammophant” would be to the original, telling El País, “I would pay a lot of money to see a hairy half-elephant mammoth thing in a zoo or wildlife park, even knowing that it’s not authentic. But it would be a mistake to call it a mammoth.” Sure, and dinosaurs likely had feathers. That didn’t stop all those paying customers from flocking to luxurious Jurassic World to see a bald half-frog indominus thing stomp around beautiful Isla Nublar, and just look how that wen… oh yeah. —Christian Niedan

Monty Rakusen/Getty Images

College was once the forge for skilled, good-paying jobs. Now? College is still important, but skills training is gaining ground.

Skills Set Career Match

Maryland is dropping degree requirements for thousands of state jobs, sparking another round of heated debate about the purpose and value of higher education. “We are ensuring that qualified, nondegree candidates are regularly being considered for these career-changing opportunities,” said Governor Larry Hogan in making the announcement. Maryland’s move follows a national trend of employers rethinking college prerequisites as a way to address labor shortages, find overlooked talent, and bolster diversity. “Employers are resetting degree requirements in a wide range of roles, dropping the requirement for a bachelor’s degree in many middle-skill and even some higher-skill roles,” according to a February report from Harvard Business School. “This reset could have major implications for how employers find talent and open up opportunities for the two-thirds of Americans without a college education.”

It also has major implications for college and universities, which have grown accustomed to selling themselves as the surest route to achieving career ambitions. There’s still a wealth of data demonstrating college graduates have far greater job opportunities, and generally better lifetime earnings, than their degree-less peers. But if employers begin opening more high-demand fields to those without a degree, that calculus could shift. “College challenges people to think critically and to grow socially and intellectually,” wrote the Washington Post editorial board in response to Maryland’s hiring decision. “But that is not the only way to acquire skills and experience, and unfortunately the price tag of a college education is something that many—particularly Black people and other minorities—cannot afford. That they are automatically blocked from even applying for jobs where they might have the aptitude—and will afford them a better standard of living—is wrong.” As that sentiment grows, the challenge of promoting higher education on the broader merits—the chance to think and learn and explore, not just to jazz up a resume—will grow with it. —Eric Johnson

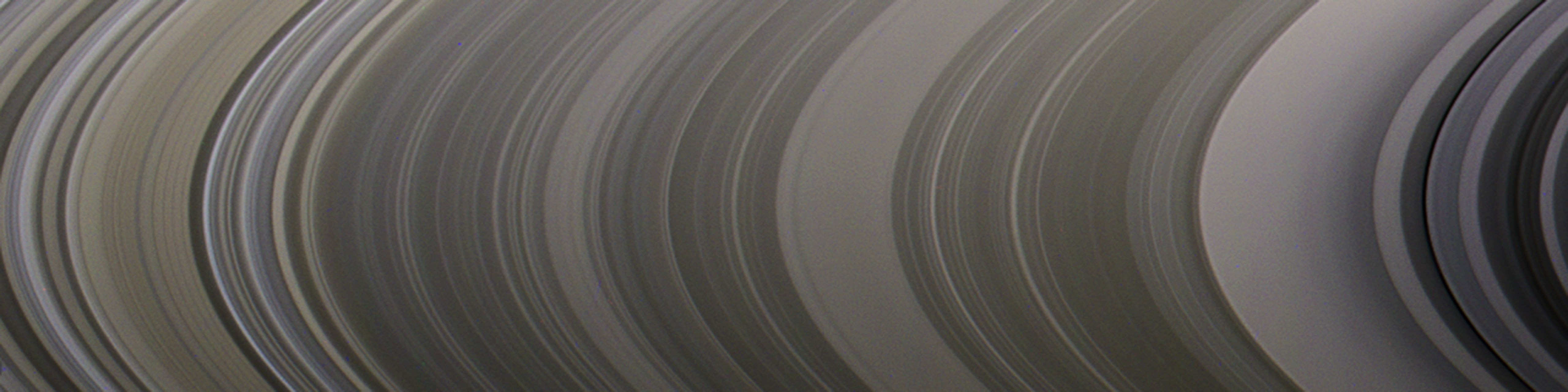

NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

This view of Saturn was created by combining 165 images taken by the Cassini probe over nearly three hours on September 15, 2006. With the planet hanging in the blackness, sheltering Cassini from the sun's blinding glare, we see the rings as never before.

Ring Drops Keep Falling On My Head

Saturn's rings are missing! Well, not quite—or, at least, not quite yet. But my entire elementary school science education was thrown into doubt this week when I learned Saturn's rings aren't permanent. And while they're not gone yet, they are disappearing. The cause is ring rain, which sounds like a horrible fungal infection. Really, it’s a phenomena where micrometeorites and the sun's radiation disturb the matter in the rings, electrifying the particles and causing them to fall toward Saturn's atmosphere, where they're vaporized. Fortunately—for anyone studying outer space or who just loves looking at cool space pics—this process is slow. The rings won't fully disappear for about 300 million years, by which time we'll probably be living across the galaxy anyways. Another, even more interesting wrinkle in Saturn’s ring cycle is that the planet hasn't always had them. Imagery from two NASA spacecraft, Voyager and Cassini, show the rings don’t have enough mass to be billions of years old, the age of the planet. Instead, their size suggests the rings are only 10 million to 100 million years old—younger than the dinosaurs! Astronomers aren't sure how the rings formed, but a leading theory is that an ancient moon of Saturn, possibly about the size of our own, got too close to the planet and was shorn into pieces, forming the rings. That planets’ rings have a life cycle shocked me—Saturn with rings feels immutable. But as I learned from The Lion King, "The circle of life moves us all, through despair and hope." In fact, astronomers predict that in 20 to 80 million years, Mars' moon Phobos will likely break apart, potentially forming rings around the red planet. Saturn's loss is Mars' gain, and the circle of life spins on. —Hannah Van Drie

PeopleImages/Getty Images

"Thanks for coming in. You're exceptionally qualified and I'm excited to hear more about your story. But first, I've got to know—can you get me a deal on a set of professional-grade steak knives?"

The Interrogative Mood

It’s easy to find reams of advice aimed at job-seekers prepping for a big interview: do your homework on the company, arrive early, think about specific examples from your résumé, prepare for the dreaded tell-me-about-a-time-you-failed question. But in today’s hyper-competitive labor market, it’s interviewers who need to put their best foot forward to convince potential hires they should join up. “When you can put a candidate at ease, create a smooth conversational flow, and elicit important information, you’re one step closer to matching a candidate to the perfect role,” writes Laura Hilgers in a post for LinkedIn’s Talent Blog. To do that well, she recommends channeling your inner Oprah. “Oprah Winfrey has made her name as an interviewer in part because of her ability to listen closely and treat people with dignity,” Hilger writes. “When you listen intently to a candidate, it helps them feel seen and heard.” She goes on to catalog interview tips from some of the other greats of the genre, including Stephen Colbert and Terry Gross, aiming for a relaxed and conversational job interview that leaves both parties feeling eager to work together.

All of this is a far cry from my first round of post-college job interviews. I wanted a policy job in the Texas state house but also needed an income ASAP, so I interviewed for all kinds of things—and a lot of it was selling: water purifiers to homeowners, temp help door-to-door in nearly empty office buildings during a recession. Knives. “Hi, you don’t know me, but this is a suitcase full of exceptional—and exceptionally sharp—objects. Can I come in?” All that halting and goofy practice talking to strangers prepared me for the interviews at the Capitol. “Are you sure you want to work this many hours for this salary?” Not exactly Oprah, but the simple answer was “yes” and it launched me into a career I loved—and still do to this day.

Whatever the interviewing approach, I'm glad to see a renewed emphasis on the human touch in hiring, especially after years of reading about AI screening tools and job-interviewing chatbots. Work is still about people—how well you collaborate, create, and communicate—all things best launched with a good conversation. —Stefanie Sanford

Dante A. Ciampaglia

From its alcove in the Vatican, a full-length sculpture of Julius Caesar extends his arm to absolve the seat of Catholicism of the sin of not giving him better placement among the other priceless artifacts and antiquities.

Et tu, NatGeo?

A decade ago, my wife and I spent 10 days in Italy, which included a day at the Vatican. Touring the center of Catholicism is as cultural as it is spiritual—art is everywhere, on the walls, on the floors, on the ceilings. In one room, literally every corner was stuffed full of relics, artifacts, and sculptures. One exceptional piece, hidden away looming over other relatively humdrum stuff, was a full-size statue of Julius Caesar at his most imperious. It was back there for any number of reasons—from sheer quantity of objects in the Vatican to obtuse politics—but it was rather majestic all the same, even as an afterthought. I found myself thinking about it again after reading classicist and historian Mary Beard’s excellent piece in National Geographic about the many, many busts of Caesar that populate the world and the difficulty in authenticating them. “There are nearly 80 ancient heads found all over Europe and the United States that have been claimed to be a true portrait of Caesar. How do we decide which are and which are not?” Beard writes. “Can we recognize his head out of the estimated hundreds of thousands of other Roman portraits that still survive, lined up on our museum shelves?”

It’s a fascinating article that sits at the intersection of art, antiquity, commerce, and, well, faith. Beard documents a few high profile Caesars that each, in their turn, stood as the gold standard—an ethereal green head made in Egypt (and possibly commissioned by Cleopatra!), a particularly superb Italian bust that fronted countless books, another excavated in Rome by Napoleon's brother Lucien—and how science and history eventually knocked them off their pedestals as the One True Caesar. But you can’t keep a good emperor down; another Caesar has popped up to lay claim to the throne, this one dredged out of the Rhône river, in the southern French town Arles. When it was discovered, Beard recounts, “the director of the team shouted, ‘Putain, mais c’est César—Damn, it’s Caesar.’” Except who can say for sure? And, really, does it really matter? Don’t all figures who existed before photography and achieved the kind of socio-historical status that Caesar has become reflections of who we want them to be? (Even photographic representations don't guard against image interpretation—look at all the ways Abraham Lincoln gets remade.) It’s a point Beard readily concedes: “The true image of Julius Caesar is always just outside our grasp. Each generation finds a new Caesar for themselves.” I love this hunt for a life-size, likelike representation of Julius Caesar created in his lifetime, and I hope we find one. I’d love to take a selfie with it! But that Vatican Caesar is my Caesar, whether I’m watching Shakespeare or reading one of Mary Beard’s books. —Dante A. Ciampaglia