In Our Feeds

Dollars for Bowling, “Crowd” Roars, and Calc Hack: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From redefining communities to trips down memory lane, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Patrick Smith/Getty Images

Who is that masked Super Bowl fan? No, really, who is it? And where are they? There's a real person in there somewhere...

Punt, Pass, and Piped-In Noise

There's a science to everything, including crowd noise. When Super Bowl LV kicked off in Tampa last week, only a fraction of the normal fan base was on hand—about 7,500 vaccinated health care workers and 17,000 paying fans in a stadium meant to hold more than 65,000. The rest of the seats were filled by cardboard cutouts (sold for $100 a pop), who served to guarantee social distance between the real humans and make the stadium look packed on television. Since cardboard can't cheer (yet—I'm sure someone is working on it!), the NFL’s production team piped in crowd noise via the stadium synthesizer. And it turns out this is a lot more complicated than you'd think. CBS Sunday Morning ran a great segment explaining how a punt cheer sounds different than what you hear for a forward-pass which sounds different from one after a sack. And timing is key, explained Vince Caputo, the head sound mixer for NFL Films. "When that pass is getting close to the receiver, you want to start cheering then, not waiting to make sure that he catches it," he said. Got to capture the anticipation! And, of course, crowd noise affects the science of home-field advantage. In November, Jason Gay at the Wall Street Journal took a fascinating look at how gamblers were adjusting to a world of empty stadiums. "What did home field possibly mean in 2020? Was there any serious advantage to a three-quarters-empty stadium with pumped in noise and a scattering of clapping?" Gay asked. Maybe the soundscape has improved since then because the hometown Buccaneers (the first Super Bowl team to play the game in its home stadium, by the way) trounced the “visiting” Kansas City Chiefs last week—to the roaring approval of a mostly cardboard crowd. —Stefanie Sanford

Sesame Workshop

Honestly, we're all a little Grover after nearly a year of pandemic lockdown.

The Monster at the End of This Blurb

One of the best parts about being a dad is sharing the books I loved as a kid with my daughter. She’s only 2, so still a little too young for The Gulag Archipelago—but the perfect age to have fun with The Monster at the End of This Book. I grew up obsessed with this Sesame Street story of Grover being so terrified of monsters that he tries to keep you from turning pages to reach the end of the book. Grover tries tying pages together, building a brick wall, appealing to your good sense, and, often, trying to guilt you into putting the book down. Published in 1971 as part of the Little Golden Books series, written by Sesame Street co-creator Jon Stone, and illustrated by Michael Smollin, this kind of metafiction would have been familiar to a certain segment of adult readers but, as this excellent Washington Post feature explores, it was a breakthrough for children’s books. And, as children’s author Mac Barnett says, perfect for its intended audience: “I think that we can mistake metafiction as sort of a highbrow, beard-strokey thing, but actually it’s just rough-and-tumble play with the rules of literature. And kids are eager to engage in that kind of play. It’s what they do all the time.” Frankly, a certain segment of adults are eager to engage in that, too. (Ahem.) It’s great to have an excuse to read The Monster at the End of This Book again, and to see my daughter get into it. She recites lines as we go, has brought some elements from storytime into her personality, and has let it shape who she is as a reader. (Her latest obsession is Mo Willems, whose books are directly descended from Monster.) I just wish the current Little Golden Books edition didn’t look so washed out and muted. Please give us a better one, Random House, pleasepleasepleasepleaseplease. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Jan Hakan Dahlstrom/Getty Images

<insert pithy Big Lebowski reference here>

Resetting the Pins

Robert Putnam is famous for diagnosing America’s loneliness, finding all the way back in 2000 that far too many of us were Bowling Alone, disconnected from the sports leagues, neighborhood associations, and long-term friendships that give fulfillment and meaning to our lives. This year, Putnam teamed up with Shaylyn Romney Garrett to tell us how to fix it. “The Progressive Era witnessed a sea change away from the increasing inequality and polarization and social fragmentation of the Gilded Age toward equality, comity, and community,” they write in The Upswing, one of the most encouraging books I’ve read in the past year. It traces the economic and social forces that brought Americans together in the early decades of the last century, and it includes a starring role for young people in pushing for productive change. Many of the reformers who started new civic associations, built new media companies, and launched new political movements were in their 20s and 30s, Garrett said during an online discussion of the book earlier this week. “It was an incredibly youth-driven movement,” she said. “If we’re going to look for an upswing today, it needs to come from those post-Baby Boom generations.” I don’t often come away from a Zoom event feeling energized, but listening to Garrett and Putnam made me want to go join a club, start a magazine, volunteer for a charity—or at least share this recommendation. —Eric Johnson

Shanestillz/Getty Images

If you used your graphing calculator to play low-fi games in math class instead of doing actual math problems, you might be a millennial.

Memory Hack

Starting in sixth grade, I attend a fancy-pants private school. It was a 60-plus-minute bus ride away from my lower-middle-class neighborhood, but it might as well have been in an alternate universe. It was all-boys from until eighth grade, and the middle school was in an old mansion on a rolling estate in the middle of nowhere to really play up the Dickensian metaphor. Kids wore clothes and carried backpacks with fancy labels. And everyone used tech that, at the time, was cutting edge: the TI-85 graphing calculator. Except me and a few others, that is, who could only afford the down-market TI-81. (Who says class systems don't exist in America!) By high school I upgraded to the TI-83, which allowed me to do more stuff—like grab games a friend programmed on his TI-86. (That friend, by the way, is a legit genius who ended up helping develop Facebook Connect and the Facebook Platform and co-creating Quora, among other things.) I was transported back to that time listening to ex-NSA hacker Patrick Wardle talk about his first hack on the Motherboard podcast Cyber. In high school, he created a program on his TI-83 (yes!) that looked innocuous, but when he entered a string of variables at the menu he'd be taken to a secret section that allowed him to quickly solve problems he was doing in calculus class. His teacher never caught on, and he passed the class. But it turns out the shortcut proved beneficial. "Coding up these algorithms for these calculus equations gave me an incredible depth of understanding of them," Wardle says. "When you're writing or implementing some code that is solving equations, you're going to gain a really in-depth understanding of those equations and then you're going to test your code. So, end result, I definitely understood these calculus equations better than any of my classmates." And it led to a career as a top-tier cybersecurity expert. TI-83 FTW! —Dante A. Ciampaglia

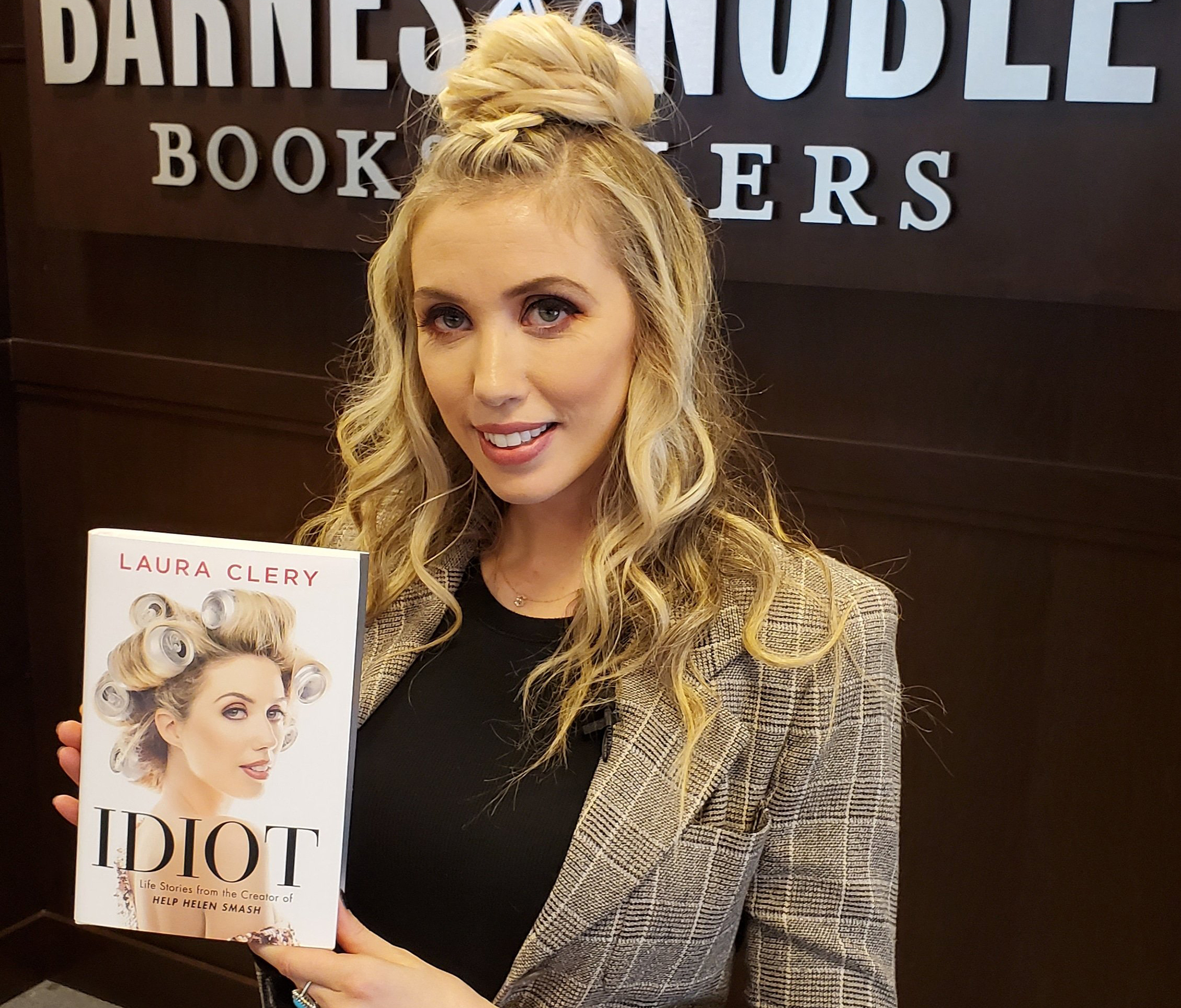

@BNEventsGrove/Twitter

Author Laura Clery with her book Idiot after a book signing in October 2019. Remember book signings? Remember being able to gather with other people at book signings?

Hard-Earned Smart Stuff

My wife has very different cultural tastes than I do. Which is great—it means we always have plenty to talk about. When I asked her if she’d like to contribute to this week’s column, she said, “Well, I’m listening to a book called Idiot.” Then she made a brilliant case for why this essay collection by Laura Clery, which deals with fame, addiction, and mental health, will definitely make you wiser. Especially if you’re like me and absolutely no sense of why things go viral on the internet or how you make a living from raunch-comedy Facebook videos. Clery is famous for turning her husband and infant son into co-stars on her gonzo videos about the anxieties of motherhood, marriage, and online celebrity. But Idiot goes deeper (certainly more so than the title suggests) about her disheartening experience trying to make it in traditional Hollywood and her narrow escape from what she calls an impulse and destructive life. It’s fascinating to hear a person who puts her domestic life on the internet describe things she once kept hidden—and the wrenching process of learning that you can change your life without losing yourself. —Eric Johnson