In Our Feeds

Mars-copters, Author Prophets, and Free Speech Zones: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From sci-fi IRL to digging in to our modes of communication, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

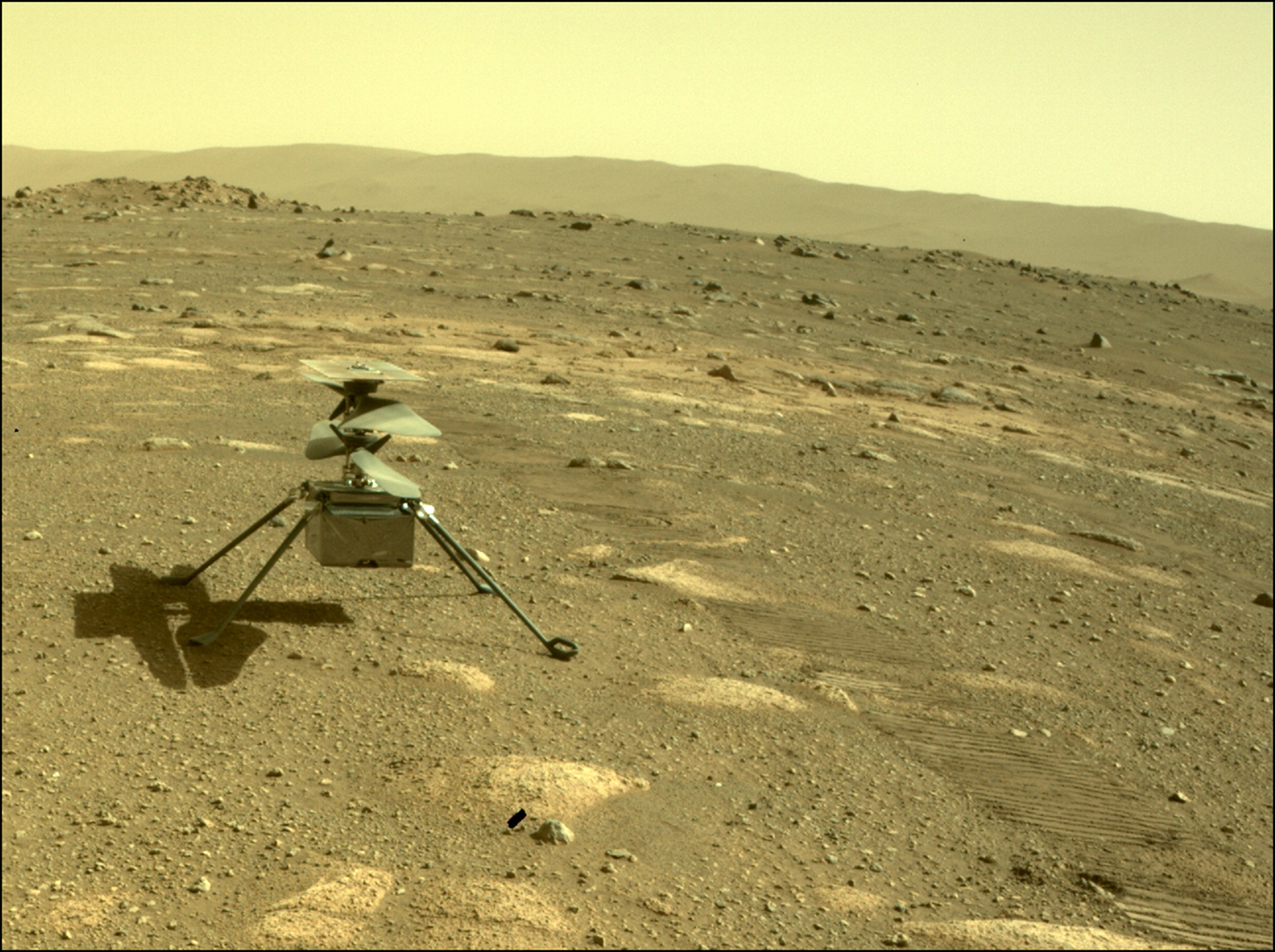

NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter can be seen on Mars as viewed by the Perseverance rover’s rear Hazard Camera on April 4, 2021, the 44th Martian day, or sol of the mission.

Do Martians Call Them UFOs?

Sometime soon, possibly by this weekend, a four-pound, dual-rotor helicopter named Ingenuity will lift off from a Martian crater and become the first aircraft to take flight on another planet (that we know of). Given that humanity just figured out controlled flight on this planet 117 years ago, that’s pretty impressive progress. The Wall Street Journal detailed some of the incredible engineering that went into building a helicopter light enough to fly in Mars’ thin atmosphere—the blades have to spin five times faster than they would on Earth—but sturdy enough to survive a rocket-powered trip across the solar system and a pretty rough landing aboard a Mars rover. “It’s like trying to build a tractor to compete in a Formula One car race,” said one of the engineers who helped design the Martian copter.

So much of the technology to do this, from the materials science required to make the blades to the miniaturization of engines and control systems to the advanced computing to actually fly the thing, wasn't ready even a decade ago. I’ve seen lots of commentary in recent years about how we’ve lost our edge in innovation, that we waste our best talent building cellphone apps for entertainment. But in a few days, when millions of people and thousands of schoolchildren tune in to watch a helicopter kick up some Martian dust, we’ll get a vivid reminder of how much stellar science is happening in universities, companies, and government agencies all over America. I think all the time about the fact that the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk and Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon took place within a single human life span, that there were plenty of people who saw both of those events during their lives. It's perfectly possible that some of the students watching Ingenuity this week will put the first human footprints on Mars. —Stefanie Sanford

Wikipedia

In a China that has gone sci-fi mad, author Chen Qiufan has become one of the country's oracles—which can put him in the crosshairs of anxious state censors.

More Like Science-Meta-Non-Fiction

The future seems to arrive faster and faster with each new technological breakthrough. The original Star Trek was set in the 2260s, and while transporters are still a ways off we achieved the communicator, eclipsed Bones’ medical bay, and one-upped whatever it was the his secretarial pool kept giving to Kirk to scribble on more than 250 years before the Enterprise embarked on its five-year mission. Sci-fi has long been a reliable feeder for our hopes, dreams, fears, and angst about the future. But what happens when our actual experience outpaces the fiction? In China, the answer is to elevate science-fiction authors “to the status of New Age prophets,” and one of the most sought after is Chen Qiufan, dubbed the “William Gibson of China” by critics. Yi-Ling Liu’s profile of Chen in the April issue of Wired is a fantastic introduction to the world of Chinese sci-fi (I finished the article with a bunch of books and short stories to read, and at least one adaptation to watch), as well as a glimpse at how the popularity of these dystopian creators has bred its own kind of dystopia. As an example: “An institute run by AI expert and venture capitalist Kai-Fu Lee’s company has even developed an algorithm capable of writing fiction in the [Chen’] voice.” Terrifying? Wait until you read the kicker! “Chen’s recent short story ‘The State of Trance,’ which includes passages generated by the AI, nabbed first prize in a Shanghai literary competition moderated by an artificially intelligent judge, beating an entry written by Nobel Prize in Literature winner Mo Yan.” The piece goes into greater detail about the personal and professional cost being seen as an oracle has taken on Chen and how he’s adapting, but it’s rare to see the stuff of science-fiction bleeding into our bleeding-edge reality—but here it is. Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to keep this crippling existential dread at bay by reading some AI-written sports stories… Crap! —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Steven Marcus/Online Archive of California

In 1964, officials at UC Berkley tried to cancel the Berkley Free Speech Movement by prohibiting on-campus protest and, later, arresting those who occupied administration buildings.

Free Speech (Minus the Legal Fees)

The last few years have seen plenty of handwringing about free speech on campus. Controversies over disinvited speakers, protests aimed at historic monuments and building names, and clashes about the balance between free expression and public safety have become common at American universities. This great back-and-forth between the conservative writer David French and left-leaning legal scholar Greg Lukianoff reminds us that these controversies aren’t new, and that there have been waves of protest and restrictions and legal fights about the First Amendment on campus going back decades. French and Lukianoff worked together at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE, where Lukianoff is now president. A lot of the podcast features these two long-time friends reminiscing about some of the more memorable cases they litigated, mostly to limit university-imposed “speech codes” that violated the Constitutional rights of students and faculty. There’s an especially fun riff about a student environmentalist who fought a years-long court battle after he was punished for protesting a parking garage.

French and Lukianoff both oppose broad restrictions on speech, but the most interesting part of their discussion focuses less on case law and more on culture. They’re both frustrated with the way partisans and provocateurs twist the meaning of “free speech” or “cancel culture,” and they want to see universities focus on the fundamentals of teaching actual pluralism and tolerance for dissent. “This is a cultural issue, and that’s why it won’t be solved by law,” Lukianoff says. “Cultural issues are all about thumbs on the scale, all about weighing. In cultural issues, it’s always going to be a little ad hoc.” And it’s always going to rely more on changing minds than changing rules, which should be the whole point of free speech, anyway. —Eric Johnson

(From left) HBO, adamkaz/Getty Images, Coleman/flickr

This first dude, on the left, Bobby Bacala? Goomba. The older stock-photo pizza guy in the middle? Seems like he could be a goomba. Those things on the right? Technically goombas, per the Super Mario Bros. universe, but not, you know, "goombas."

*Extreme Italian Hand Gesture Emoji*

My dad, along with his mom and two siblings, immigrated to the United States from Italy in 1960, which makes me a fiercely proud first generation American on his side of my family. They were members of the last major wave of Italian immigrants, which meant I wasn't raised around people who tried to beat the Italian out of me. I mean, look at my name! But while I often heard stories of the farm and village they left behind in Pizzoferrato, I wasn't taught Italian or schooled in old-world customs. È così, as far as being Italian is concerned, which left me to work out what that meant on my terms. That often led me to investigate corners of the culture and language—and to be super judgey of second- and third-generation Italian-Americans who seemed right out of central casting: the open shirt and gold chains, the endless parroting of lines from The Godfather and Goodfellas, and, above all, the constant use of words like mozzarell and goomba. There's a vowel at the end of mozzarella! C'mon! And gavadeel instead of cavatelli? Seriously? Santa pazienza!

Those twin experiences collided in Kisten Martin's essay for The Believer "A Brief History of the Word 'Goomba'". As a kid who experienced goomba as an epithet in Reagan’s Make America Great Again ‘80s, I will hate the word forever. Still, Martin's piece gave me a new appreciation for it and it's linguistic and cultural origins. In short, it's derived from the Napulitano word cumpare, which was then put through the meat grinder of southern Italian dialects and the unique American watering down of speech. "I don’t remember formally learning the word," Martin writes, "it was simply in the soup of language surrounding me in a place where most people don’t actually speak Italian or the dialects of their grandparents’ regions, but they do hold on to slang." She confesses to prefer slang that began as insults, such as gidrool, which means someone who's buffoonish; she accurately cites Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio as examples. It's such a perfectly Italian sentiment. The piece is great, and I learned a lot about what I hear spoken in my Italian-American neighborhood. But even if there's a good cultural reason for gabagool, I still reject that ingiustizia against the Italian language! —Dante A. Ciampaglia

An interpretation of the author's experience learning about AI tools and filters used to airbrush social media users' appearances.

The Young and the Restless Urge to Airbrush

I don’t have Snapchat. I take no selfies of any kind. And the only “beauty” products I use are soap and a hat. I’ve been overdue for a haircut pretty much my entire adult life. So I find it bizarre and unsettling to know that there are legions of tweens and teens spending their time perfecting the art of iPhone airbrushing, using the ever-more-advanced filters and image touch-up software on social media apps to change the way they look—and the way they think about beauty and self-worth. "More and more young people—and especially teenage girls—are using filters that ‘beautify’ their appearance and promise to deliver model-esque looks by sharpening, shrinking, enhancing, and recoloring their faces and bodies," reports MIT Technology Review. "Through swipes and clicks, the array of face filters enable them to adjust their own image, and even sift through different identities, with new ease and flexibility."

People have been editing photos since the dawn of the medium, of course. What's new is that AI makes it incredibly easy to change major parts of your appearance as a matter of routine. And those technologies coincide with the rise of online "beauty influencers'' who reach tens of millions of followers with intimate YouTube videos and TikToks. They're changing the way products are marketed and the way a whole generation of young people think about body image. "As with gaming, it’s the interactivity of the web, particularly YouTube (the fun of following along with tutorials about how to contour eyes to make them appear larger, for example) and Instagram (where you boastfully show off your face’s final look) that has made beauty’s pop-culture gambit such a success," wrote the New York Times' Vanessa Grigoriadis in her profile of influencer-turned-beauty product pitchwoman Addison Rae. "In our new virtual society, the same beauty industry that was once maligned has been embraced as a universal good." Sounds like a lot of pressure to me. I'll stick with the hat. —Eric Johnson