Interview

(Mostly) Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Pencils

Author and entrepreneur Caroline Weaver sharpens our pencil history in her new book

The pencil is one of those everyday objects we don't typically think about much. It seems as if it has always been and will always be a thin stick of wood, most likely painted yellow, with a pink eraser on one end and a sharpened point of graphite on the other. But when was the last time you thought about why a pencil looks the way it does? Why is it yellow? Does that metal ring holding the eraser have a name? What’s up with that whole No. 2 thing?

Caroline Weaver, pencil expert and owner of CW Pencil Enterprise in New York City, answers those questions and many others in her new book Pencils You Should Know: A History of the Ultimate Writing Utensil in 75 Anecdotes. Shaped like a pencil box, the accessible and illuminating book sharpens our pencil history by examining a selection of important and curious pencils. And it places this seemingly simple tool in the larger context of history, from industrialization and globalization to climate change and influencer culture.

Weaver spoke with The Elective at her shop (which, yes, smells like a giant box of fresh pencils) about the book, her love of pencils, and why the No. 2 pencil became our go-to writing instrument in school.

Chronicle Books

How did you get into pencils?

It was really just a childhood collection. I grew up in a creative household where we just had art supplies and stationery around all the time. I'm 29, so I'm just on the cusp of having been a young child with no technology in the house, and that collection turned into an interest in history as I got older. But primarily, the pencil is the tool that I've used for my entire life.

Was there one type of pencil that made you realize there's something more to it than just a writing instrument?

I grew up in rural Ohio, and when I was younger there was no shopping online, so we didn't have access to a lot of the really, really nice pencils. We did have a really cool, super-old office supply shop in town that had a bunch of, like, Black Warriors and Venus Velvets and pencils like that that had probably been sitting on their shelves since the 1970s. But I remember when I was probably 9, my mom's friend who lives in Washington, D.C., told her that there was a new Ticonderoga called the Ticonderoga Millennium and that we could buy it at our local Walmart. It was something that was actually available where we lived. And my mom went out and bought this new Ticonderoga Millennium, and as a family we decided that that was the best pencil we could get our hands on within 15 miles of where we lived. So we used those, and that was a very good pencil. This was back when Ticonderogas were still made in the U.S. It was their first version of the black ones that they make now. It was a really nice matte black finish with really funny typography, and they had a really nice eraser.

Ticonderoga pencils are now made in China. Does that matter?

The Ticonderoga now is not even close to what people knew it as. It frustrates me that people in America still think that that is the pinnacle of yellow school pencils. It absolutely is not. There are so many better ones that are still made here that are the same price that are just so much better. But I guess with a lot of these American companies, too, it's the heritage of the company that's important and it's the families who run them that make sure that they're still making products with the same integrity they did 50 years ago. With Ticonderoga, they have an office here but they're owned by an Italian conglomerate and everything is made in Mexico and Taiwan. There's a big quality discrepancy between the Mexican Ticonderogas and the Taiwanese Ticonderogas. They're completely different. The Taiwanese ones are better centered, the wood is a little bit better. The Taiwanese ones are just better than the Mexican ones. And if you flip the package over, you can see in the small print where they're made.

What's the better yellow pencil people should get?

There's one called the General Semi-Hex that's been around for almost as long as the Ticonderoga, made by a smaller, family-owned company in Jersey City. It's also yellow. It also has an eraser. But it's much, much better quality. And there's another one made by a U.S. company called the Musgrave Harvest that is so inexpensive. For what it costs to buy them in bulk, it's significantly less than what even a Ticonderoga costs and is infinitely better. Especially for kids—they're probably sharpening them in a really nasty electric sharpener at school and the pencils just get eaten. If they're not centered properly or if they're broken on the inside, that's a problem because they're going to keep sharpening and sharpening them and nothing's going to happen.

Chronicle Books

Three examples of pencils included in the book "Pencils You Should Know: A History of the Ultimate Writing Utensil in 75 Anecdotes" by Caroline Weaver, published by Chronicle Books 2020

How did you decide which pencils to include in the book?

About half of them are favorites of mine that I knew I wanted to include, but a lot of it was just selecting them based on what narrative I wanted to tell. I knew that an important part of the history [of pencils] were the World War II-era plastic barrels, or some of these 1980s novelty pencils. I wrote down all the types of pencils I needed to hit and then went through my personal collection, the shop's collection, the collections of some people that I know, and kind of matched up what I thought the best example was for each of those that had the best story. The one I was afraid I wasn't going to get in is the Thoreau pencil. But the Morgan Library was super-nice about lending me images and giving me permission to include the ones from their collection.

Do you have a personal favorite?

The Futura is one of my all-time favorites. I love the really wacky Space Age pink one from the 1950s. And the miniature rock collection pencil was a really important one for me to include. My grandma used to buy me those when I was really young at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. I wish I still had them. I probably lost all the rocks and probably chewed the eraser.

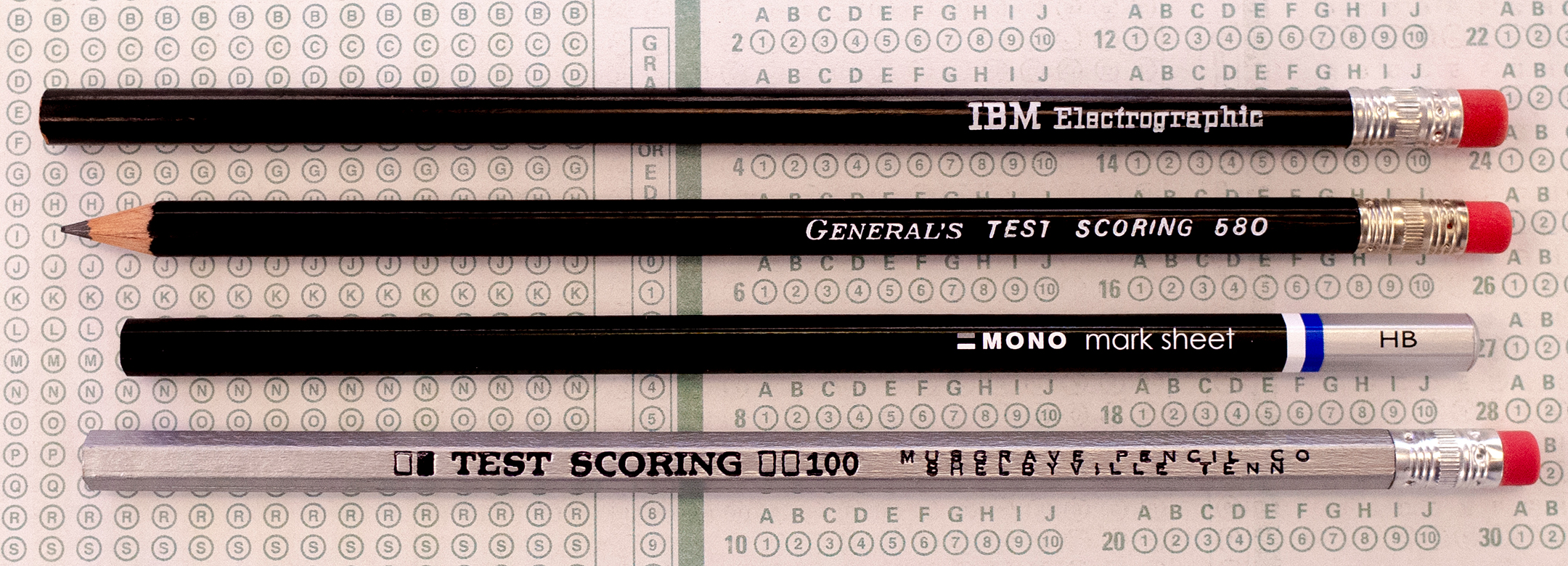

You include the IBM Electrographic Mark Sensing Pencil, which was designed for taking electronically graded tests. Having grown up with teachers saying, "Come with a No. 2 pencil," I didn’t realize there was a pencil made specifically for test taking.

In the 1930s through probably the 1950s, there were many, many companies who were making those: the IBM ones, the Generals ones, the Musgrave ones. In Japan, there are still several that are manufactured. All the main brands in Japan, I think, still make what they call a Mark Sheet pencil. I think it really was only something necessary for these very early test-scoring machines.

What's the origin of the No. 2 pencil? What does the number represent? And how did it become the standard pencil?

There's no confirmed answer to that. Like a lot of things in the pencil industry, much of the story is undocumented; it's very old history. It has to do with a lot of family history, so there have been a lot of disputes over whose story is correct. First of all, the 1–4 pencil grading scale is strictly an American thing. No one else in the world uses that; they use an HB scale, and a number two is equivalent to an HB. It's supposed to be the middle of the scale, a very balanced graphite. But apparently, and this is the story I choose to believe, it was Henry David Thoreau who came up with the 1–4 scale in the U.S., and this would have been in the 1800s. Henry David Thoreau's father, John Thoreau, was one of the first pencil makers in America, and before his son went on to become a very famous writer, most of his career was dedicated to helping his father with his business, before he went to Harvard to study to be an engineer. He was a real innovator, and from what I understand about his history he was kind of bored. This is such a lame family business, what do I do to make this more interesting? And so a lot of very early pencil innovation, like pre-Industrial Revolution technology, happened because of Henry David Thoreau. Word on the street is that he heard that over in Europe, they were making what they called polygrade pencils where there are different ratios of graphite and clay. So he did pretty much the same thing here and made four, and 2 ended up being the most balanced one. That was the one that people decided was for general use.

Dante A. Ciampaglia

Examples of different kinds of test-taking pencils, including the IBM Electrographic Mark Sensing Pencil.

Why do Americans use numbers as opposed to the HB system?

It's just the thing that stuck. Pencilmaking in general caught on in America very, very quickly. They were made in Europe first, but it was Joseph Dixon who really was at the forefront of developing equipment during the Industrial Revolution for mechanizing the manufacture of pencils. This idea of mass production of pencils happened very quickly in the U.S. Up until that point, with the Thoreaus and all these guys in Massachusetts who were carving pencils, they were all using this scale, and when they started mass producing them, it's the only thing they knew. So that's just what they did, and then it stuck.

Another interesting fact from the book is that attached erasers are only found on American pencils. Why?

That's another thing that there's no definite answer to. The first attached eraser was patented in the U.S. in the late 1800s, and it caught on. In the early 1900s, when they figured out that you can use this bit of metal called the ferrule to attach it, that's when it really stuck—and it just never caught on anywhere else. There's a real trend with that, like with the grading conventions, the ferrule, even the color yellow—all of those things are particular to American pencils. I don't know if that says something about how American industry works, or how it did back then, but once they did it one way that's how it was always done.

Why did yellow become the standard? Is that another piece of pencil lore that has no sort of definitive answer or origin?

The one thing that is agreed upon is that in the late 1800s, when people started painting pencils, the finest graphite in the world was coming from China. And so yellow became a color that was associated with a pencil because it was a way of indicating that your pencil was made with superior Chinese graphite. The Koh-i-Noor was the first yellow pencil. The original ones were dipped in 14-karat gold, and they cost, I think, seven times the cost of a normal pencil. It was crazy. It was very controversial. It was the first expensive pencil to be painted. At the time, only cheap pencils were painted because it meant you were hiding something; that you weren't using high-quality wood and so you were trying to hide the woodgrain by painting it. And then this one came out, which is seven times as expensive as the average pencil, and it's painted yellow, and it's dipped in gold. It was completely obscene.

What's the state of American pencil manufacturing today?

There are really only three companies that make pencils in the U.S. now. Two are in Tennessee, and one is in Jersey City. One of the ones in Tennessee and the one in Jersey City are still family owned. General Pencil Company in New Jersey has been around since the 1880s, and Jim Weissenborn, their current owner, I think is fifth generation. That's a thing that happened really in the 1980s and the 1990s: A lot of these companies were buying each other out or they were merging with larger European companies. But the ones that are still around are really good about maintaining the heritage of their brands, and they celebrate that, and they make a lot of the exact same products they made 100 years ago, which I think is so cool. The typography on these old American pencils is awesome, I love them. And they're inexpensive, too. They're a lot less expensive than the ones you get from Europe or from Japan. I feel like it's my job to remind people, “No, don't use your Ticonderoga. There are better pencils that are still made in this country that have a more interesting history.”

Dante A. Ciampaglia

Author Caroline Weaver's store, CW Pencil Enterprise, carries a range of pencils from around the world.

Why is the pencil still a valuable tool in this digital era?

It doesn't have a battery, so its battery can't die. It's not a pen, so it can't run out of ink or just stop working. It's such a perfectly simple tool that's more reliable because it doesn't rely on a spring or a battery or anything like that. I tend to romanticize all of this, but I think writing with a pencil is unlike writing with anything else because there's a certain freedom to it, especially as opposed to writing with a pen because you know that you can erase. I don't think there has ever been or will ever be another writing tool or communication technology that's as tactile as the pencil.

I’m sure it takes a lot to go from tree to finished product. Is there a sustainability question? How are pencil manufacturers reacting to the possible impact climate change will have the pencil?

As of yet there hasn't been a major impact, though it is a thing pencil companies are becoming more concerned about. It's a standard now for pretty much any pencil company in the world to make their pencils out of [Forest Stewardship Council]-certified wood. Most pencils are made out of cedar, which comes from California or Oregon, and the main company that farms that wood and cuts it into slots and sells it for the pencil industry, they were the pioneers in this whole FSC-certified pencil wood thing. They do a pretty good job of reforestation and making sure that they're doing everything as sustainably as they can. There are several companies that started only making pencils out of woods that are native to where their factories are. In India, there's a family-owned company, Hindustan Pencils, that's an umbrella of brands. They make 9 million pencils a day. It's ridiculous. It's a humongous company with facilities all over India, and they only use wood farmed under their control and native to India. Even Caran d'Ache in Switzerland has started testing making some of their pencil models in Scots pine, which is native to Switzerland.

But at the end of the day, a pencil is degradable, it’s compostable. When you use it, there's nothing left except a ferrule and an eraser, if that's the kind of pencil you're using. I like to throw my pencil shavings in my fireplace; they make a good fire starter. So the object itself is pretty waste free. But, yeah, the farming of the wood is a concern, but I think a single pencil has less of a carbon footprint than a pen.

In the book, you call John Steinbeck a notorious pencil influencer. Do you consider yourself a pencil influencer, notorious or otherwise?

(laughs) Maybe? If there is anybody in the world who could be considered a pencil influencer, it's probably me. I guess we could say that; I'm okay with that. But I prefer “expert” to be how I'm described.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.