In Our Feeds

Oregon Trailblazers, International Jetsetters, and Graceful Agers: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From the numbers that rule our lives to how our lives are designed, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

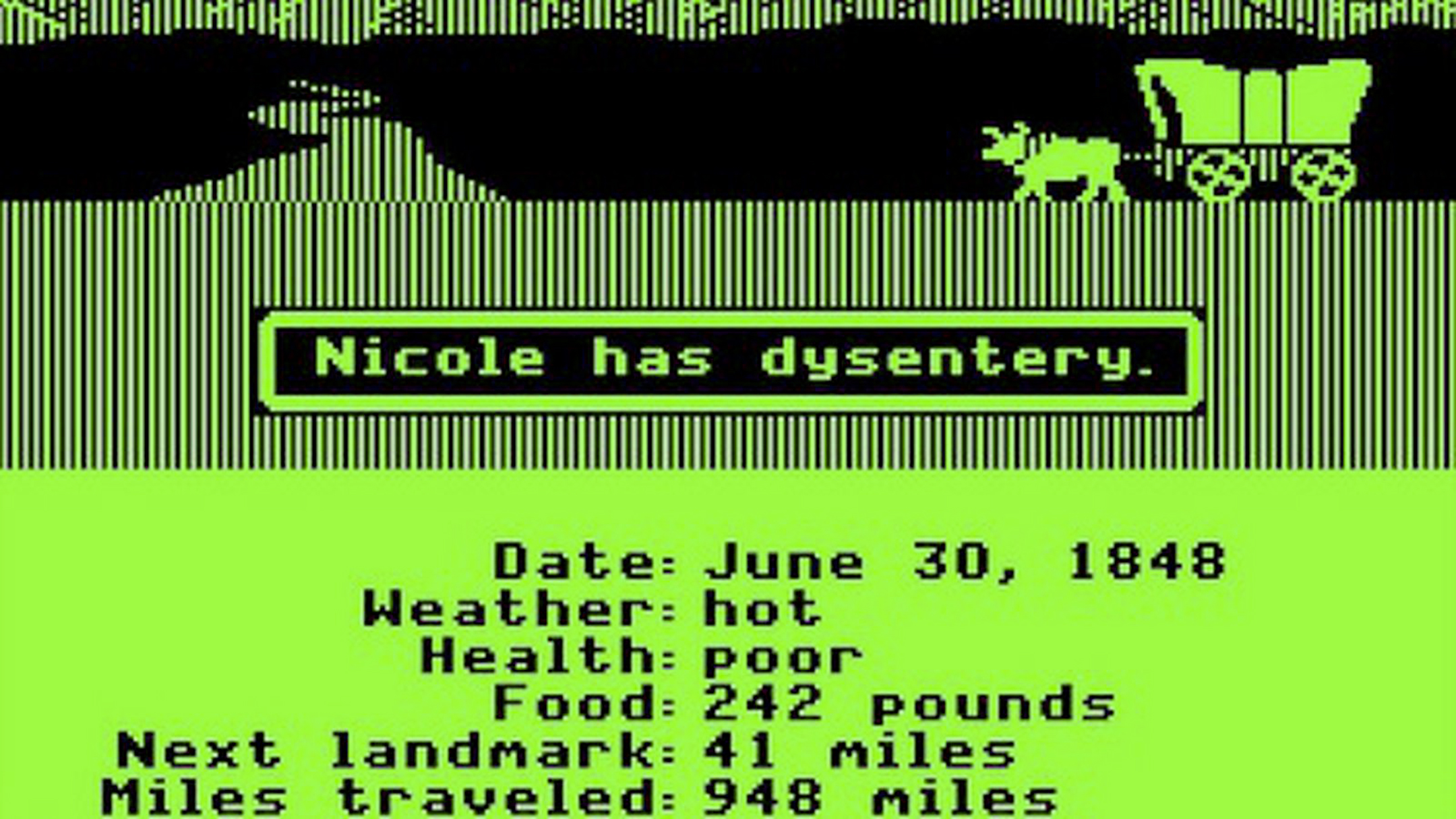

Anyone who has ever seen this screen while playing The Oregon Trail knows where it leads. And it ain't Oregon.

The Not-So-Dusty Trail

Dying of dysentery was a rite of passage for people my age. In the computer lab, I mean. One my first exposures to personal computing was in the late 1980s, sitting in front of a green-type-on-black-screen terminal as dot matrix printers scratched out text-based illustrations and as silicon circuitry burned inside the taupe machines to play The Oregon Trail with my classmates. It was supposed to be a way to build typing skills, but all we in the Nintendo Entertainment System generation cared about was having a chance to play a game during school. The goal was to get your 19th century wagon train to the west coast via the Oregon Trail as you contented with busted wagon wheels, dwindling supplies, and various physical ailments. Often, the journey ended with “Dante has died of dysentery.” Cool! Let’s go again! It was a formative experience for kids like me and a couple cohorts after. But until reading Greg Toppo’s excellent piece in The 74 about the game, I never appreciated just how old The Oregon Trail is—it turns 50 on December 3!—or who created it and why.

The short version is Don Rawitch, a 21-year-old student-teacher in Minneapolis, was leading an 8th grade history lesson on westward expansion. To make it interactive, he created a dice-and-card game that relied on a map drawn on butcher paper. “One of his roommates came home, saw what Rawitsch was doing, and envisioned something completely different,” Toppo writes. That roommate, Bill Heinemann, was a math teacher and ended up coding the game; another roommate, Paul Dillenberger, also a math teacher, debugged it. “Its first young players encountered it on a paper roll fed into a hulking teletype, connected by a phone line to a mainframe computer miles away,” Toppo continues. There were no pictures or graphics, only lines of type and the occasional ringing bell.” The Oregon Trail was a computer game that arrived five years before the PC, and it would’ve been lost to time had the three developers not saved the code and, when one of them went to work for the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium, brought the game to the MECC, which got it into the hands of students around the country. One estimate has it the game has moved 65 million copies. Kids loved it—Toppo gets into how it fostered a spirit of democracy in the classroom—and its impact can be felt well beyond the classroom and memes—it relied on mini games to hold student interest, which has become a cornerstone of video game development. But Rawitch, Heinemann, and Dillenberger never saw a dime. It’s a wild story worthy of its subject, and one of those slices of pop culture history that helps bring our contemporary experience into sharper focus. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Thanasis Zovoilis/Getty Images

"Did I ever tell you about that time when I was 68 and totally nailed that Salesforce presentation? Now that was living!"

Ain’t Nothing But a Number: Age Edition

The fine folks at the Stanford Center on Longevity believe that many of today’s young people will live to see their 100th birthdays thanks to advancing medical science. “In the United States, as many as half of today’s 5-year-olds can expect to live to the age of 100, and this once unattainable milestone may become the norm for newborns by 2050,” reads the preamble to the New Map of Life initiative. “One of the most profound transformations of the human experience calls for equally momentous and creative changes in the ways we lead these 100-year lives, at every stage.” Life spans have risen an astonishing amount in the last two centuries (though that growth has stalled out in the United States, thanks to public health challenges like opioid addiction), but most of the basic milestones—school, marriage, career—are still squeezed into a compressed period. The Stanford crew thinks it’s high time we rethink the way we organize our lives, spreading things out so we can be more balanced in the present.

For starters, they want to see education become less of a mad sprint from kindergarten to college and more of a lifelong pursuit. “Rather than front-loading formal education into the first two decades of life, we envision new options for learning outside the confines of formal education, with people of all ages able to acquire the knowledge they need at each stage of their lives.” That means making more room for older students in college and adapting K12 schools to move students along at a much more individualized pace. The New Life Map also calls for major shifts in how we work, with fewer hours each week but a later retirement age. “Over the course of 100-year lives, we can expect to work 60 years or more,” the researchers predict. “But we won’t work as we do now, cramming 40-hour weeks and 50 work weeks a year (for those who can afford vacation) into lives impossibly packed from morning until night with parenting, family, caregiving, schooling, and other obligations.” A longer life means we can afford a slower pace, making room for an “open-loop” approach of jumping out and back into the workforce as family and personal demands shift over time. “For younger workers, an ‘open loop’ can relieve pressure at other life stages—for example, at the outset of parenthood, when the demands of peak career-building years collide with the time demands of starting families, especially for women.” Amen, I write, as my children try to crawl over the keyboard. —Eric Johnson

gece33/Getty Images

"This is your captain speaking. We'll be taking the scenic route this evening. Our estimated time of arrival will be in 18 hours. Hope you brought snacks because this flight will not be serving meals."

Flying the Frenemy Skies

This Thanksgiving, instead of celebrating with turkey, I attended the wedding of two friends in India. It was a joyous, beautiful occasion, but I did have to survive a very long, 16-hour direct flight on American Airlines from New York to Delhi. I had no reason to give much thought to the length of the flight until I received an email from the carrier apologizing for my flight being rerouted. That was confusing—everything went smoothly. When I looked into it, I discovered that the next flight out was diverted to Gander, Canada. I immediately imagined the worst—running out of fuel, a medical emergency, some other disaster. But it turns out the reason was less dramatic: American doesn’t have the right to fly over Russian airspace for its India route. As a result, it’s several hours longer than other airlines' New York to India flights (16 hours vs. 13 hours on another airline). And if there's ever a delay at the start of the flight—in this case, the plane after mine left four hours late—the crew will surpass the maximum hours they can work. So when the next American flight to India was delayed, the airline could either cancel it entirely or reroute and bring on a new crew. It chose the latter.

That naturally led me to wonder: Is it normal not to have a permit to fly over Russian airspace? And how many long-haul flights does this affect? As of October 2021, apparently quite a few. According to a letter from Airlines for America, a group that represents carriers like American, Delta, and United, these airlines had impressed upon the State Department to "act urgently" to secure the rights to fly over Russia. The companies feared that without action, they would be forced to stop or reduce the frequency of certain flights. The State Department secured these rights, but Russia offers a narrow approval window for permits—and there’s speculation that the diverted New York-Delhi flight missed that window. The article alludes to the fact that airline flight permits are part of a bigger-picture geopolitical challenge. The relationship between the U.S. and Russia is facing numerous strains: President Biden is threatening sanctions against Russia if they invade Ukraine, and both countries have expelled more than 50 of the other country's diplomats. Understanding this context adds an additional layer of nuance to American Airlines’ struggle to obtain a flight permit—and makes me grateful to have arrived back home safely, without an international incident. —Hannah Van Drie

Mironov Konstantin/Getty Images

If only it were so easy to improve your credit score...

Ain’t Nothing But a Number: Credit Edition

Years ago, I went to a recruiting event for a prestigious scholarship program (as a paid staffer, not a prospective recipient) and listened as a panel of highly accomplished alumni dispensed life advice to the young students: Follow your passion. Take risks. Be curious and open-minded. You know the stuff. At the very end, they reached the youngest alum on the panel and asked what advice he would give his 18-year-old self if he could travel back in time. "Establish credit," he declared, offering the most pragmatic wisdom of the night. "Otherwise, no one will rent you an apartment." Sound advice! Credit scores are one of those bizarre artifacts of adult life that nobody teaches you about in school but turn out to have a massive influence on whether you'll be able to own a house, buy a car, or get top-secret clearance for your new job at the National Security Agency. "A credit score predicts how likely you are to pay back a loan on time," explains the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. "Businesses might use your credit reports to determine whether to offer you insurance; rent a house or apartment to you; provide you with cable TV, internet, utility, or cell phone service. If you agree to let an employer look at your credit report, it may also be used to make employment decisions about you."

For the millions of people with low credit scores, this presents a big problem. Now a new crop of startup companies is trying to improve the credit model by looking at a wider and more creative range of inputs. "Established players and slick start-ups alike are collecting and crunching all manner of other data to determine who ought to get a loan and how much they should pay," reports the New York Times. "This so-called alternative credit scoring could have profound effects for consumers, many of them minorities or low-income individuals, who can be asked to hand over more intimate personal information—like their spending habits and details of their college degree—in hopes of getting a loan." It'll be a while before we know if a bigger-data approach to lending means more opportunities for marginalized borrowers, or just more surveillance. But this basic trade—more personal data in exchange for wider access—is becoming the norm across much of our economy. —Eric Johnson

Steven Pisano/flickr

Just because a scene such as this—and the resignation these adults clearly feel—is part of the experience of living in New York with kids doesn't mean it has to be accepted as a fact of life.

Rubber Baby Buggy Bumpers

In my Brooklyn neighborhood, I’m smack dab between the Carroll Street F/G subway and the Smith-9 Street F/G, which is the next stop south and the highest rapid transit station in the world. In 2013, it reopened after a two-year, $32 million, desperately needed renovation. There’s still perpetual construction, the interior is still dark and grimy, and the escalators still routinely break down—a drag because it’s also still really tall, and if the moving stairs are out then you’ve got to schlep up a couple hundred exceptionally steep steps. (But it has nice new exterior cladding, so let’s call it a draw.) For all those reasons Carroll is my preferred station, but I’ve gotten more acquainted with Smith-9 Street taking my daughter to school, sometimes with a stroller. And that has also gotten me acquainted with the highest rapid transit station in the world not being accessible. No ramps. No elevators. Just lots of steps, moving and otherwise. That’s a drag for someone like me—I can haul the stroller and the kid and just feel like my lungs have collapsed by the time I reach the platform—but absolutely alienating for the people in wheelchairs and walkers who routinely gather outside to wait for a bus. It was a pretty galling (and personally embarrassing) realization that the station was elevator-less. Not surprising, though: Only 25% of NYC’s 472 subway stations are accessible, per Gothamist. But a lot of infrastructure money is about to flow into places like New York, and The New Republic’s Kendra Hurley has a novel suggestion on addressing this accessibility issue: make cities friendlier for strollers.

From dumpy metro stations to bus rules prohibiting open strollers to roadways with unsafe walking conditions, the design of our built environment is hostile to people with kids. (Try hauling a stroller, loaded with a sleeping toddler and all the accompanying gear, down slush-covered steps while kitted out to battle brutal winter conditions and laser-focused on not slipping down the stairway and then you can maybe think about ragging on us New Yorkers.) But as Hurley rightly points out, cities are hostile to any pedestrians who aren’t able-bodied or sans car. “This is not just an issue for people with children. Think of the elderly and people pushing carts with their shopping bags,” Hurley writes, adding later, “Treating strollers and caregivers like an afterthought might seem like a benign oversight in transportation planning, but its damage reaches beyond inconvenience and isolation for caregivers and safety hazards for kids. It preserves the long U.S. legacy of withholding government support for families with young children.” She goes into the (slow-moving) work Los Angeles planners have done to address these issues, which is as good a place as any to begin digging deeper into solving this failure of urbanism. But even just giving voice to this problem via this piece feels like a long-overdue acknowledgement that things can be built better. And should be. It gave this city-loving urbanist parent a lot to chew on. Which I’ll do as soon as I apply some Icy Hot to my shoulder. And lower back. And knees. (Install an elevator at Smith-9 Street, MTA!) —Dante A. Ciampaglia