In Our Feeds

Time Tunnels, Robo-cakes, and Potty Talk: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From catching up with old friends to discovering new ways to bake, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

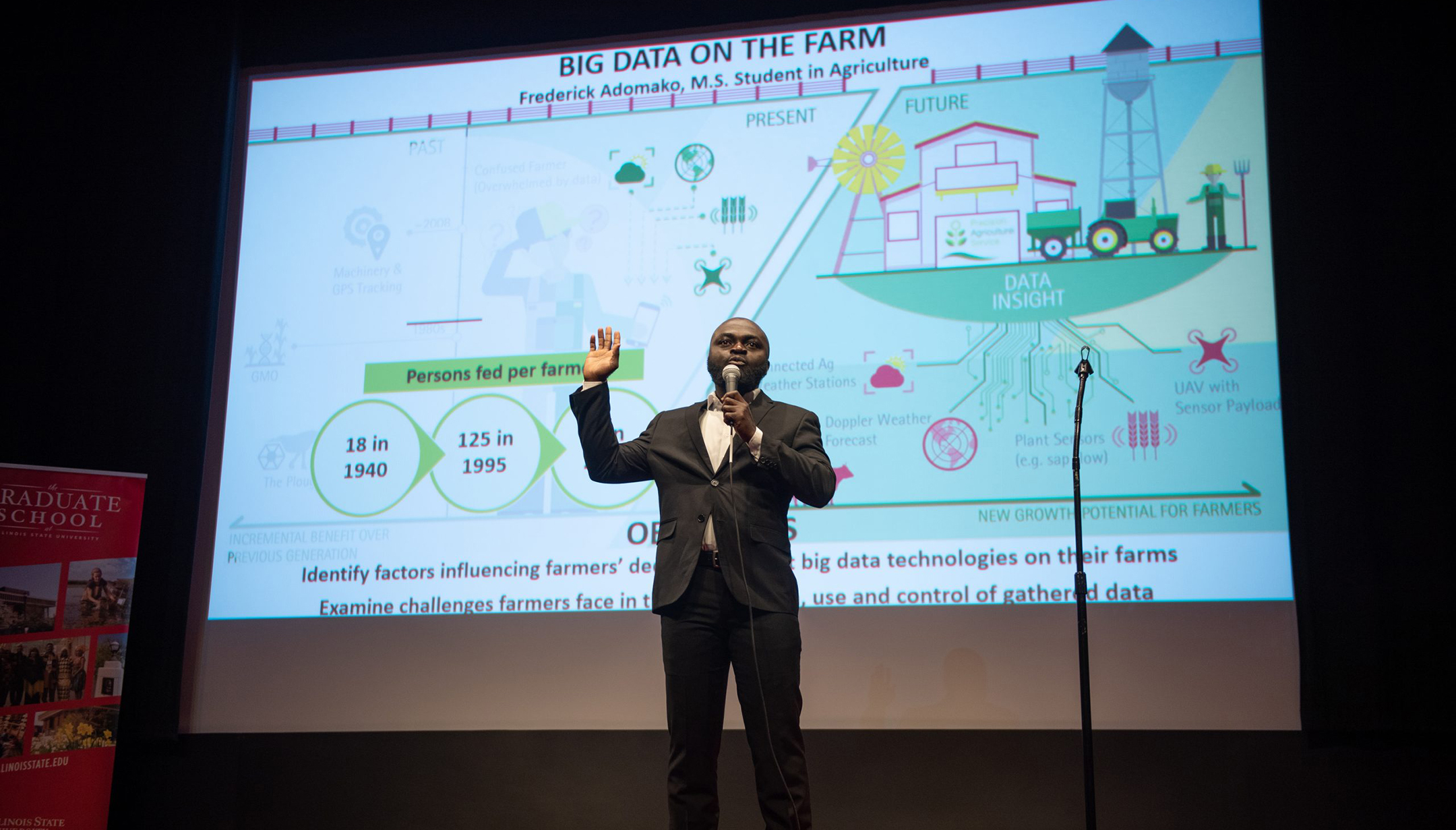

Illinois State University

If you can't pitch your thesis research in three minutes or less, should you even really bother? (Here's Frederick Adomako from Illinois State University's Department of Agriculture doing just that in 2020.)

Pitch Sessions

Could you condense a scientific manuscript into an elevator pitch? Entrepreneurs do it all the time, but aspiring academic researchers aren’t usually rewarded for brevity. The Three Minute Thesis competition, founded by the University of Queensland, is working to change that. Graduate students from astronomy to zoological sciences have to condense their thesis research into a single slide and a three-minute talk, stripping out as much jargon as they can along the way. Universities around the world have adopted the competition as a way to teach public communication skills and push future faculty members to share their findings with the wider world. “I think research is really inaccessible, and I think being able to communicate research out in a clear, concise and effective way to everybody is a really important skill that a researcher, or any person, needs to know,” master’s student Zack Jenio told the Technician, the student newspaper at North Carolina State University. Jenio is studying comparative biomedical sciences at the university’s College of Veterinary Medicine, which means his lab work is especially tough to condense. “It was really nice to have this experience because before it was a bit difficult to concisely explain my thesis to someone who might not have all of the scientific knowledge.”

I’m serving as a judge for this year’s Three Minute Thesis competition at UNC Chapel Hill, where I’ve listened to students pitch their research on the respiratory effects of wildfire smoke, the beneficial attributes of gut bacteria, and the effect of kombucha tea on nematodes, among other topics. They’re evaluated on how well they can strip away dense scientific language and convey the real-world impact of their work. As science has grown more complex and academic specialties have gotten narrower, that ability to communicate outside of one’s discipline is key to maintaining public support and finding creative collaborations across different fields. Especially after the rancor and confusion surrounding public health protocols over the past two years, there’s a renewed interest in the scientific world about how to share findings with the public in a way that’s compelling and trustworthy. “Scientists have come to understand that strong communication is an essential part of what it means to be a scientist rather than a burdensome add-on,” writes Laura Lindenfeld, who leads a center for science communication at Stony Brook University. “As part of this shift, many new training programs have emerged to prepare scientists to communicate and engage with different audiences.” Three Minute Thesis is an excellent start. —Eric Johnson

Catherine Lane/Getty Images

The only thing worthwhile about changing the clocks in the fall is gaining an hour of sleep. But, honestly, wouldn't we all trade that for never having to ask "When do we change the clocks back?" ever again?

A Case of the DSTs

Time is inexorable; time waits for no one; time marches on; lost time is never found again—except in the fall, when somehow everyone in the world agrees to throw an extra hour on the clock. I’ve always been fascinated by daylight saving time. It seems incredible that all of humanity somehow got together and agreed to… change time. Cooperation on that scale is pretty mind-blowing when you think about the level of political, economic, and cultural organization it takes to tinker with something as elemental as dawn and dusk, but we manage to do it year in, year out.

Of course, we’re still Americans, so all that cooperation happens against a backdrop of constant political squabbling about whether to change daylight time, get rid of it altogether, or just make it permanent. "More than a third of U.S. states now back a permanent shift to daylight saving time,” reports NPR. “If that happens, it would be a final victory for a plan that businesses have praised for more than 100 years.” I didn’t know that the major backers of our national clock-reset have long been merchants, which value the added hours of daylight as added hours for shopping. “If you give workers daylight, when they leave their jobs, they are much more apt to stop and shop on their way home,” explains Tufts University professor Michael Downing. The business barons weren’t wrong: a 2016 study by JP Morgan Chase found that credit card spending ticks up when daylight savings tick into gear, and takes a dive when we move sunset forward by an hour each fall. “This finding is consistent with the idea that consumers with jobs may have limited time to shop during the work week,” the bankers concluded. “If daylight affects the decision to patronize a merchant, we would expect that losing an hour of daylight would have a larger effect when there are fewer hours available.” Maybe when we’re all avatar-shopping in the metaverse, this won’t matter so much. —Stefanie Sanford

Patrick Wymore/Netflix

Boy, that cake looks good enough to ea... RUN! It's become sentient! Grab the kids! Hide the baking powder!

BB-Ate

I love the understated drama of The Great British Baking Show, but recently I discovered another confectionary program that might take the cake. Picture this: baked goods that not only float but also steer and sail; robots made out of food that are also functional. Competitors on the new Netflix show Baking Impossible must navigate these feats of bakineering (as they call it) in a variety of fascinating challenges. I am completely hooked. But I also learned there's a psychology behind America's love of baking and cooking reality TV. There are countless articles explaining why we always go back for seconds with these shows. One theory is vicarious consumption—we get to watch and imagine what the food tastes like without having to cook it ourselves. This Psychology Today article describes this feeling as multimodal mental imagery, or "mental imagery in one sense modality (vision) that is triggered by another sense modality (hearing)." Our brains enjoy this kind of stimulation, making cooking shows a true sensory experience even though we aren't tasting the food itself. I also read a less sciencey suggestion: pure stress relief. One article even described cooking and baking shows as equivalent to Hallmark rom-coms. Not only do we get to watch food come together from start to finish, which can generate a sense of accomplishment, the shows also follow a formula and we know we'll get a happy ending. I definitely relate to some of these ideas. While I have thoroughly enjoyed watching talented bakers and engineers create concoctions that are edible and functional, I will save the actual bakineering to the experts. —Hannah Van Drie

Columbia Tristar/Courtesy of Getty Images

This may or may not be a candid photo from the author's wedding weekend. And that may or may not be the author on the far right.

The Millennial Big Chill

I went to a wedding last weekend, easily the largest social event I’ve attended since the pandemic, and because it was the wedding of a college friend I reconnected with people I hadn’t seen in quite awhile. A lot changes in this era of life—marriage, kids, careers, moving across the world—which means there’s an awful lot to catch up on after a half-decade absence. That’s what makes old friends such a joy: you get to reconnect and hear about someone else’s life, while being prompted to revisit and rethink your own path. “These friends function as conduits to earlier versions of ourselves that are inaccessible day-to-day but that contain hugely important insights,” according to the School of Life, a London-based nonprofit that aims to condense the wisdom of the ages into handy guides for a fulfilling life. “In the company of the old friend, we take stock of the journey we have travelled. We get to see how we have evolved, what was once painful, what mattered or what we have wholly forgotten we deeply enjoyed. The old friend is a guardian of memories on which we might otherwise have a damagingly tenuous hold.”

You also get a glimpse into roads not taken. One of my fellow groomsmen at this wedding was a college friend who had similar interests, a similar path through school, and a completely different trajectory in the world after graduation. I stayed close to home and settled into college-town life; he took corporate jobs in California and Switzerland, working his way into the tech industry. Yet both of us have landed mentally in about the same place: trying to be decent dads, looking for a way to rebalance away from careers and more toward family without losing the thread of satisfying work. It made me think about Joshua Rothman’s beautiful 2019 essay on becoming a parent, and the way our aspirations require us to become different people. “Your life choices aren’t just about what you want to do,” Rothman argued. “They’re about who you want to be.” That has always struck me as a better way of thinking about how to spend my time. What kind of person do I hope to become, and how would that person spend their days? Keeping up with old friends, for sure. —Eric Johnson

Stephen Chernin/Getty Images

When you gotta go, you gotta hold it if you're out in public. Unless you're lucky enough to be find one of the increasingly dwindling number of public facilities.

We’re Number Two! (We Wish…)

Stories about America lagging behind other developed nations on things like math, science, and health care can seem a dime a dozen. But the stinky state of the nation's standing when it comes to public bathroom infrastructure was a new one to me. “In 2011, a United Nations-appointed special rapporteur who was sent to the U.S. to assess the ‘human right of clean drinking water and sanitation’ was shocked by the lack of public toilets in one of the richest economies in the world,” writes Elizabeth Yuko on Bloomberg CityLab. “According to a ‘Public Toilet Index’ released in August 2021 by the U.K. bathroom supply company QS Supplies and the online toilet-finding tool PeePlace, the U.S. has only eight toilets per 100,000 people overall—tied with Botswana.” Yuko’s piece, “Where Did All the Public Bathrooms Go?,” is a fantastic and incisive plunge into the history of America’s public lavatories—and why there are so few of them—ranging from the Victorian era to the Progressive movement to Jim Crow to 9/11. The tl;dr: America’s woeful global position is the result of decades of infrastructural neglect, shrinking political will, and growing avoidance of hard conversations about the social implications of letting people relieve themselves in public. “Who gets access to the bathroom really could be summarized as who should have access to public space and public discourse,” says Laura Norén, an NYU postdoctoral associate and co-editor of Toilet: The Public Restroom and the Politics of Sharing. “Somehow, that crystallizes around the bathroom, because people’s fears are the highest in the bathroom.”

Like so many other issues, the pandemic has given the paucity of public privies some urgency: When everything shuts down and people are out in the world, where are they supposed to relieve themselves when there are no public toilets? (That struggle is real, as I learned while desperate for a loo while out on long walks with my toddler daughter in the early days of the pandemic.) I don’t think I ever expected to read such a deep-dive on bathrooms, but I’m glad Yuko’s piece plopped into my feeds. It taught me a lot and revealed the very real effort to improve this very important infrastructure failing, which is led by people who really know their… stuff. —Dante A. Ciampaglia