From the Archive

Policy Brief: The Digital Divide and Educational Opportunity

From the August 1999 issue of The College Board Review comes a prescient warning about the development of online opportunity—and who stands to lose out

The digital divide—and its stubborn persistence—is an issue we’re keenly focused on here at The Elective. Often inequities in access to high-speed broadband internet and hardware like Chromebooks and tablets can feel like problems unique to this moment in our technological experience. But, as we’ve noted in previous archival pieces, The College Board Review is often a helpful tool in keeping us honest about just how long some conversations and about problems confronting America’s students have been going on. And how much work has gone into solving them.

So it is with the digital divide, which popped up as the focus of a one-page policy brief in the August 1999 issue of the magazine. Written by College Board’s Lawrence E. Gladieux, executive director for policy analysis, and Watson Scott Swail, associate director for policy analysis, the piece is a zoom-in on a section of their report The Virtual University and Educational Opportunity, published in April 1999.

The starting point is the growth of distance learning in the days of what we’d now call Web 1.0, but its theme is the kind of socioeconomic and racial gaps that were fissures in 1999 but have widened to chasms in the decades since. “Virtual universities will only benefit those who have the necessary equipment and the expertise to feel comfortable with the new technologies,” Gladieux and Swail write. “And the reality is that students who come from low-income and minority backgrounds are less likely to have been exposed to computers and the internet at home and in school.”

This policy brief is an interesting snapshot on a time when there was a seemingly omnipresent optimism swirling around the internet and its potential, particularly for education. Gladieux and Swail’s research is a prescient warning light that our digital future won’t be all Star Trek utopian equality because our then-digital present wasn’t.

From our 2022 vantage, their work reads as stingingly familiar. But it’s also further proof that data doesn’t lie—we just have to be clear-eyed enough to understand what it’s saying.

Distance education has been around in some form since the nineteenth century, but its growth has surged in the 1990s with the advent of the World Wide Web. The vision of students earning certificates or degrees without ever setting foot in a classroom has captured the imagination of education entrepreneurs and Wall Street investors. Many traditional colleges are scrambling to offer courses online, and a variety of for-profit training providers and brokers are fueling the market for electronic delivery of higher education.

Yet we have little information on how many students are actually making use of online course offerings, nor do we know much about the effectiveness of instruction received online. Computer-based technologies have created a surging market so new that there is very little experience, much less systematic data, on which to base predictions about the future.

What we do understand is this: Virtual universities will only benefit those who have the necessary equipment and the expertise to feel comfortable with the new technologies. And the reality is that students who come from low-income and minority backgrounds are less likely to have been exposed to computers and the internet at home and in school.

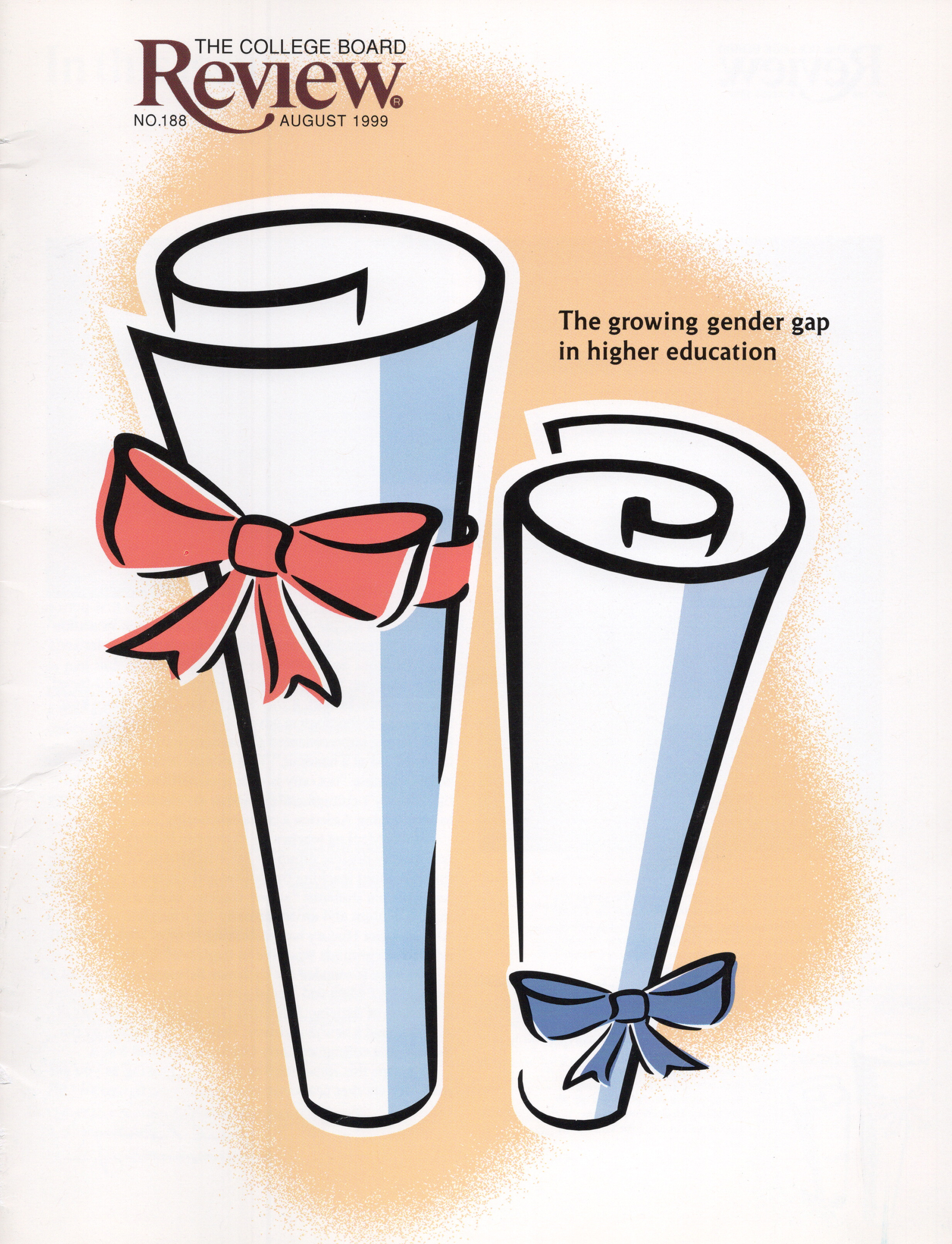

While computers may seem ubiquitous in today's society, their distribution is highly stratified by socioeconomic class. Figure I illustrates the direct correlation of household income to computer and online access. With respect to race and ethnicity, data also show that Black and Hispanic families have less than half the access afforded White and Asian families.

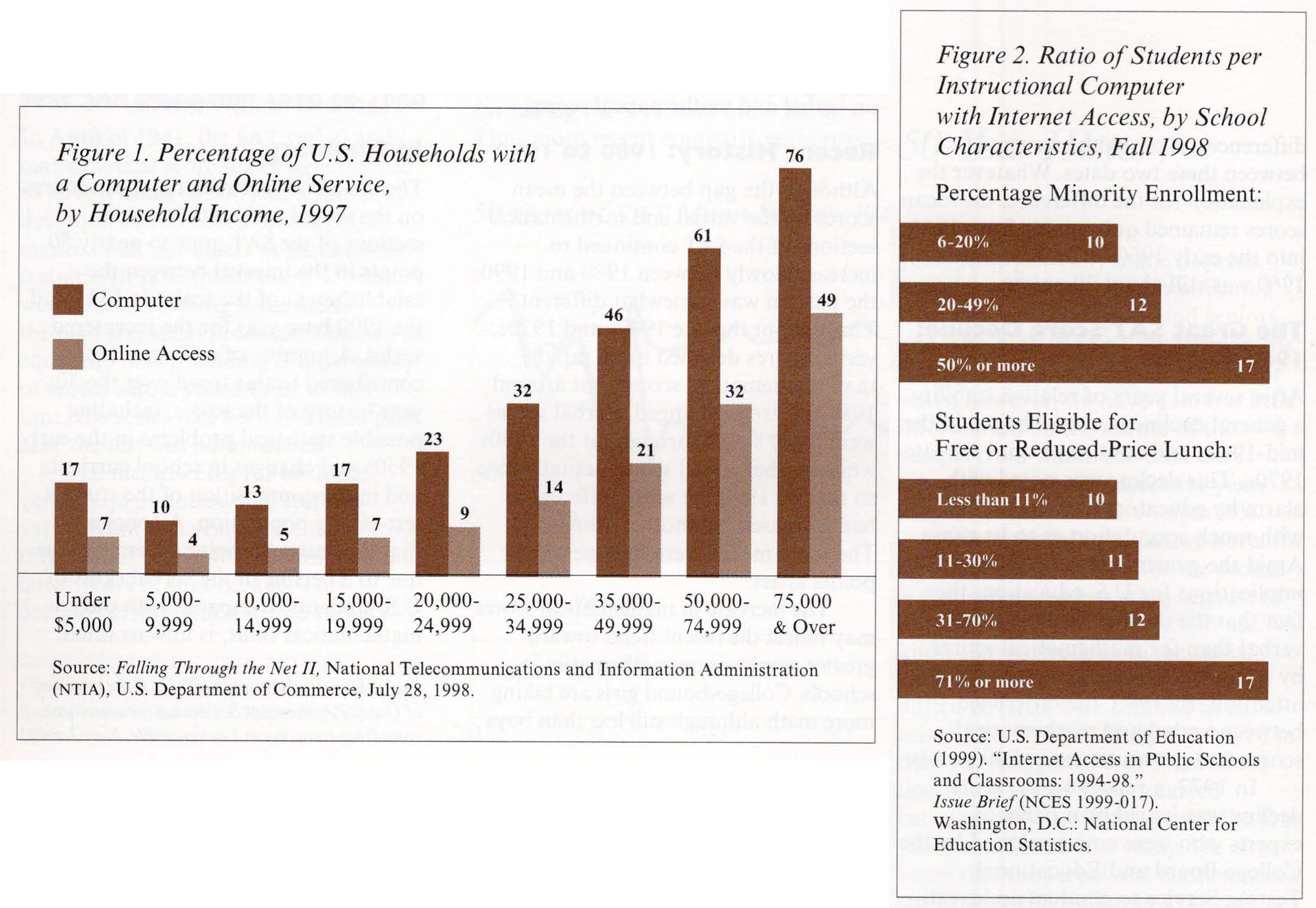

Similar disparities are reflected in K–12 schools. Figure 2 shows that the ratio of students to computers with internet access is highest in schools with the largest proportion of minority and poor students. The availability of technology decreases as the percentage of such students increases. Not surprisingly, differentials in experience with internet technology appear when students enter postsecondary education. Recent data from UCLA's American Freshman Survey indicate that students in public Black colleges are about half as likely to use email as students in private, predominantly White institutions.

Great strides have been made in broadening access to computer technology in recent years. But as with many other social indicators, the playing field remains tilted toward the affluent. Although education is heralded as the great equalizer, technology appears to be a new engine of inequality. The most advantaged citizens—and schools—are most able to benefit from cutting edge technologies. Advantage magnifies advantage.

While the World Wide Web shatters barriers of time and space, it also creates new obstacles to educational access simply because of the differential availability of the required technology.

The marketplace alone will not fix the problem. Policymakers and education leaders must work to reduce the digital divide and increase learning opportunities for all.