News

Remote Learning Lessons from Los Angeles

With little national data available, the results of LAUSD’s “moonshot” to get students online points to challenges districts face closing the digital divide

As covid-19 closed schools around the country, educators knew they had to work fast. Their students were now suddenly remote learners, and not everyone had the tools they’d need to attend class from home. To help close the digital divide, many districts

quickly coordinated the mass distribution of laptops, Wi-Fi hotspots, and other tools to ensure students could participate in online instruction.

It was a massive effort. Boston distributed more than 30,000 laptops to students. New York City put 321,000 internet-ready iPads into students’ hands. Chicago provided 128,000 devices to get kids online. It’s hard to tally exactly how many devices were sent out nationwide, but one consulting firm concluded that sales of mobile PCs to K–12 schools rose almost 20% in the first half of 2020.

The level of outreach and the availability of technology varied from district to district, even school to school, and we likely won’t know what worked, what didn’t, and its impacts for quite some time. But the nation’s second-largest school district has released data on its push to get students connected, which gives the nation a window into what worked—and what didn't.

Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

Heather Pick of Plainview, a parent in the Plainview - Old Bethpage school district, picks up a Chromebook at the district administrative office on March 16, 2020, to allow students to continue their studies at home.

Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) serves more than 550,000 students across a range of income and demographic breakdowns. It’s larger than some state education systems—only New York City boasts a larger public school system. The sheer size and diversity of LAUSD makes its remote-learning push unique. On the other hand, that scale also means the district can provide a broader view than most districts about what happened with remote learning this past last school year.

At the start of the pandemic, approximately 250,000 families (about one-fourth of the district) lacked the resources needed for remote learning. This problem was particularly acute in East and South Los Angeles and among students of color. LAUSD authorized an emergency investment of $100 million to get laptops and hotspots into the hands of students who needed them. On May 11, Superintendent Austin Beutner, describing the transition to online learning as a “moonshot,” said, “The rocket has been built and liftoff has occurred.” He announced that 96% of elementary school and 98% of both middle and high school students were connected and able to participate in online learning.

Problem solved? Not quite. The ability to log in is one thing. Actually logging in is another thing. The digital divide, it turns out, is about more than technology.

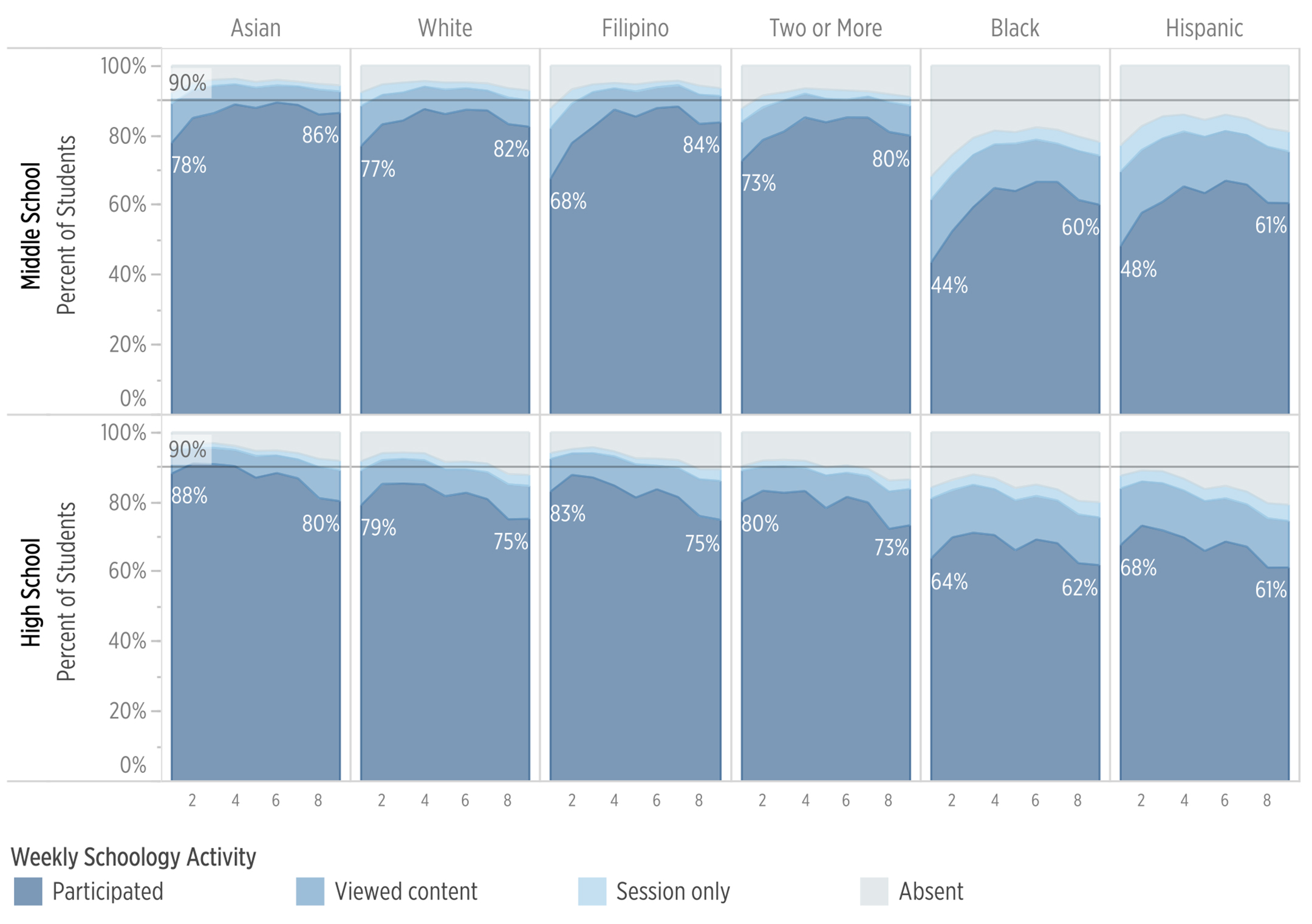

In July, LAUSD released its report on middle school and high school usage of the Schoology learning platform, which it uses for all digital engagement. The majority of remote learning took place inside the platform. This makes it possible to examine student activity as a proxy for who participated and how much once Los Angeles schools moved online.

Almost 100% of middle and high school students logged onto Schoology at least once between March 16 and May 22. But on any given day, 39% of students were counted as absent because they weren’t active on the platform. Simply logging on to the platform or looking at an assignment counted as activity. Data points went beyond mere activity, though, to also reflect participation, which included taking a test, turning in an assignment, or engaging in an online discussion. On average, only 36% of students actively participated each day.

LAUSD, "Student Engagement Online During School Facilities Closures," page 7

Students active on Schoology at least once per instructional week, by race/ethnicity and school level

The report, compiled by the Independent Analysis Unit of LAUSD, acknowledges that daily metrics are likely not the best measure of activity. Some teachers gave students multiple days to complete assignments, and neither teachers nor students were required to be active every day. About 80% of middle school students logged on each week during the school closure. In March, about 90% of high school students were active each week, but that dropped down to around 80% by May. The proportion of middle school students who actively participated each week increased during the period, peaking at 71%, while high school participation dipped from a high point of 74% in week 2 down to 64% by the last week of school.

It’s difficult to make an apples-to-apples comparison between participation in remote learning and regular school attendance before covid-19. Based on enrollment and average daily attendance numbers, approximately 72% of LAUSD students were in school during 2018-19. Weekly participation in remote learning is a lower bar to meet than daily attendance, of course, but the numbers for middle school students, at least, were comparable.

Participation rates for Black, Latino, and Hispanic students lagged behind their white and Asian-American peers by as much as 20 percentage points. Participation rates were also lower for students from low-income backgrounds, English language learners, students with disabilities, and students who are homeless or in foster care.

Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images

IT Support Technician Michael Hakopian (R) distributes devices to students at Hollywood High School on August 13, 2020 in Hollywood, California.

The report showed participation gaps between districts. In School Board District 3, which covers most of the West San Fernando Valley, almost 78% of middle school students were participating weekly by the end of the school year. In District 7, which stretches from South LA to the Los Angeles Harbor, however, only 55% of students were participating. The size of these disparities within a single school district hint at the disparities that typically play out across the nation.

The LAUSD report doesn’t attempt to explain why student engagement varied so much or what drove lower participation among many students of color and low-income families. The lack of regular access to technology needed to get online partly explains it, but there’s much more to the story. The fact that almost all students could get online at some point suggests additional, deeper problems in remote learning, such as what kind of supports students need at home to participate regularly.

It’s a question that will grow more pressing this year, as Los Angeles and many other school districts prepare for a school year of at least some remote learning for an indefinite amount of time. Collecting data on how students are engaging with online classrooms—and what tech they have, or don’t, to give them that opportunity—and then responding to it quickly will be crucial for school districts as they try to close the participation gap.