In Our Feeds

Retraining America, Humanitarian Aid, and Utopian Dreams: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From constitutional champions to cities of hopes and dreams, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

A security guard wears a face mask while standing outside shuttered shops and a 'For Lease' sign amid the global coronavirus pandemic on March 30, 2020 in Los Angeles, California.

Spring for Retraining

“Millions of jobs that have been shortchanged or wiped out entirely by the coronavirus pandemic are unlikely to come back, economists warn, setting up a massive need for career changes and retraining in the United States,” the Washington Post reported this week, citing data from a variety of different government reports and consulting firms. “Indeed, the number of workers in need of retraining could be in the millions, according to McKinsey and David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who co-wrote a report warning that automation is accelerating in the pandemic.”

This reality represents a massive challenge to the country’s education sector. The United States allows for far more economic churn and “creative destruction” than other developed economies—the Wall Street Journal ran an excellent piece contrasting European and American approaches to unemployment during the pandemic—but we don’t do nearly enough to help people transition into new careers. Most four-year colleges aren’t designed to serve adult learners who have jobs and families and can’t afford to take a multi-year break from working. And most community colleges, saddled with very low levels of per-student funding, struggle to help a majority of their students reach graduation. The last major recession in the U.S. saw explosive growth in for-profit schools, which left millions of Americans in debt without any worthwhile degree to show for it. How we handle a similar moment of disruption now, with a huge portion of our working adults considering a career change, will go a long way in determining whether Americans regain their faith in higher education as a path to opportunity. —Eric Johnson

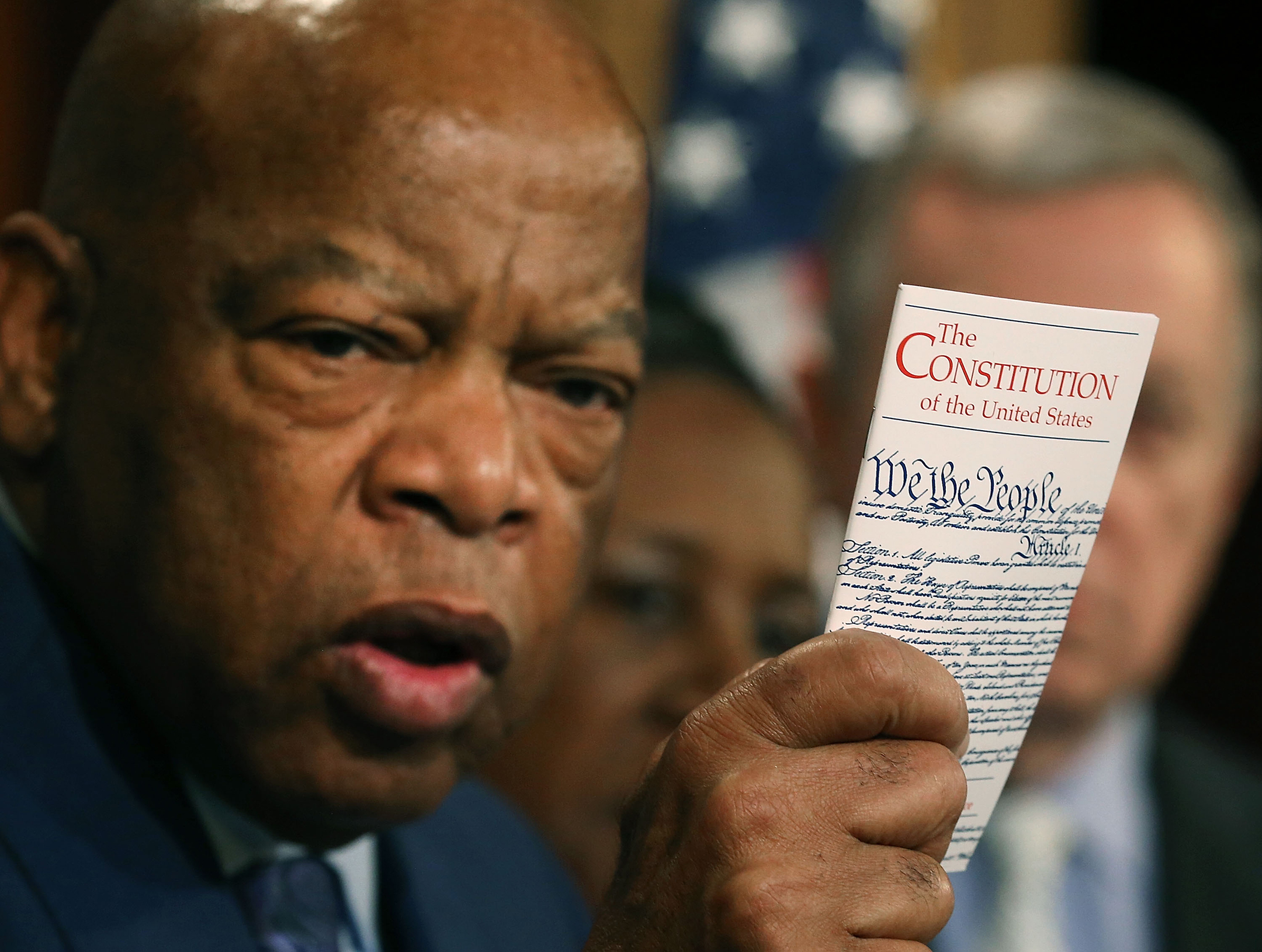

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Rep. John Lewis holds a copy of the U.S. Constitution during a news conference with Senate Democrats and members of the Congressional Black Caucus on Capitol Hill on March 3, 2016.

Unconventional Constitutional Wisdom

One of the joys of being involved with the Institute for Citizens and Scholars is meeting people like Danielle Allen, professor of government at Harvard and a brilliant thinker about American history and government. She wrote a beautiful and moving essay for The Atlantic last year on “the flawed genius of the Constitution,” arguing that a realistic view of American’s past can still lead the great-great-granddaughter of an enslaved American to feel a sense of empowerment over America’s future. “The Constitution is a work of practical genius,” she wrote. “Those who wrote the version ratified centuries ago do not own the version we live by today. We do. It’s ours, an adaptable instrument used to define self-government among free and equal citizens—and to secure our ongoing moral education about that most important human endeavor. We are all responsible for our Constitution.”

I spoke with Dr. Allen last week and she talked in part about striking a balance in the way we teach history, giving students an honest rendering of the past while preserving a sense of hope and agency about the future: “How do we narrate our history, being clear-eyed about both our achievements and our failures?” Getting that balance right helps decide whether the next generation feels a sense of ownership and belonging in our democracy; whether they feel the vital institutions of government can represent them and welcome their energy.

Like so many of the best teachers I meet, Dr. Allen spends a lot of time thinking about this. She used the phrase “scaffolding agency,” meaning you start small. Teach students how to lobby for reform at their schools or in their local communities. Show that the mechanisms of government can be responsive when you have the knowledge to use them. “Remarkably, the Constitution’s slow, steady change has regularly been in the direction of moral improvement,” Allen wrote in that Atlantic piece. “In that regard, it has served well as a device for securing and stabilizing genuine human progress not only in politics but also in moral understanding.” How lucky her students are to have such a marvelous teacher, and how lucky that all of us get to share in her best lessons. —Stefanie Sanford

Byron Smith/Getty Images

Refugees from the Tigray region of Ethiopia wait to be transferred to a camp with more infrastructure at a UNHCR reception area in the east Sudanese border village of Hamdayet on December 6, 2020 in Hamdayet, Sudan.

City of Brotherly Love

The catastrophe of the covid-19 pandemic can feel like it has recontextualized or simply overwhelmed every other humanitarian disaster, from homelessness to food insecurity and hunger to the global refugee crisis. We Americans don't have a great recent track record on any of those issues, especially when it comes to people seeking safety, asylum, and opportunity at our southern border—a tragedy given the "Shining City on the Hill" many of us believe this country represents. But we in the land of plenty would be wise to heed the example of Sudanese in Hamdayet, which borders Ethiopia and has become a destination for refugees fleeing the violence in their nation's Tigray region. “We must empathize with one another,” Hassina Mohamed Omar told the New York Times. “They knocked on our door and said, ‘Do you have space?’ And what do you do? You house them.” The Times story documenting how residents of Hamdayet—who already have very little—have opened their doors and lives to their neighbors—who have even less—captures the best of humanity. That the Sudanese are mostly Muslim and the Ethiopians Christian adds an added dimension of the selflessness and love. And this isn't a case of one person being offered an extra room for a finite period; this is whole families being given shelter for however long they need it. “They are like our brothers,” Mohamed Ali Ibrahim, who has sheltered five people in a mud hut, told the Times. “We have not given them a time limit and we cannot do that because these are people coming to us for refuge.” For all sorts of reasons, this story hit me hard. But this is the example of common humanity and neighborly aid we need to see more of, and emulate—and not only as Americans.

While I'm here: Patrick Kingsley's The New Odyssey, from 2017, is maybe the best book on the global refugee crisis you can read. And Giancarlo Rosi's 2016 documentary Fire at Sea, filmed on the Sicilian island Lampedusa that has played such an outsize role in refugees' attempt to reach Europe, is essential. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from the Trumpauer-Mulholland Collection

Page from a a pamphlet promoting Soul City in North Carolina.

Lost City of S

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when the federal government was in the business of trying to create brand new cities across the country. It was the 1970s, and there were deep concerns that urban crime and decay would make metropolises like New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles ungovernable. The newly-created Department of Housing and Urban Development responded by investing millions of dollars into a program to launch built-from-scratch cities—occasionally in very unlikely places. One such project was Soul City, North Carolina, an imagined “Black utopia” in a deeply rural area about halfway between Raleigh and Richmond. Civil rights icon Floyd McKissick, a man who led the Congress of Racial Equality and marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., decided that one of the best ways to advance the cause of Black equality was to create a mecca of Black-owned industry in the North Carolina piedmont. “McKissick’s dream was about economic equality, not separatism,” Thomas Healy writes in the fascinating new book Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia. “For Black Americans to be truly free, he believed, they needed power—economic power.”

I visited what’s left of Soul City before, after reading an article about McKissick’s lost dream in Oxford American. It’s a patch of unfinished roads and a few small housing developments about an hour north of where I live, in the thriving metro area of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. But I didn’t know the full story, or how Soul City—a product of the fierce debates about integration, independence, and power that remain as relevant as ever—fit into the contentious history of the civil rights movement. Even though the planned community was never completed, Healy thinks there’s something to be learned from McKissick’s approach and the level of support it earned from allies across racial and political lines. “McKissick succeeded in persuading powerful people that what was in the interests of Black people in North Carolina was also in the interests of White people in North Carolina,” Healy told me in a Zoom conversation earlier this month. “And to me, that’s a pretty remarkable accomplishment.” For more on Soul City, check out this Atlantic essay from Healy and an excellent New Yorker piece on Black capitalism in the Soul City era. —Eric Johnson

RyanJLane/Getty Images

Unless these N95 masks are part of the right supply chain, you're probably not going to see these on store shelves, either.

Mask And You May Receive

With unemployment numbers surging again this week, pity the small business owner who faces laying people off for no good reason. For example, consider this recent New York Times headline: “Can’t Find an N95 Mask? This Company Has 30 Million That It Can’t Sell.” That poor fellow retooled his Miami factory, but found that bulk buyers, such as hospitals, aren’t willing—or able—to mess with their supply chains. He’s also being squeezed by Facebook and Google, which imposed severe restrictions on the online sale of masks to prevent gouging and counterfeits. (Buy American, unless it’s an N95 mask.) This got me thinking about the glut of shortages we’ve endured this past year, some logical, some nonsensical. Start with the obvious things related to healthcare, hospitals and PPE: face masks, hand sanitizers, surgical gloves, hospital beds, ventilators. (And for a brief time, morgues and refrigeration trucks.) The first big consumer run was on toilet paper and cleaning supplies. And then things got a little goofy: freezers and mini-fridges, jigsaw puzzles, kettlebells, blood, baking yeast, dogs and cats for adoption, PlayStations, Nintendo Switches, laptop and tablet computers, bikes, small gold bars and gold coins, lumber, ground beef, and even new cars (not enough chips). And here’s an ominous one: America is also “suffering” from a shortage of guns and ammunition. And it’s not because they’re being beaten into plowshares. —Bob Roe