In Our Feeds

Taco Talk, Media Meltdowns, and Flagrant Flops: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From street food influencers to pandemic mystery solvers, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Alvarez/Getty Images

Pics or they didn't happen—any taco influencer worth 25 Gs a month will tell you that.

Livin’ La Vida Taco

“What does the future of tacos look like?” I ask myself that question at least once a week. And if you’ve got the right skillset, pondering the destiny of the fried-and-filled tortilla could net you some serious coin as the Director of Taco Relations for the spice wizards at McCormick & Company. “As the Director of Taco Relations, you will be McCormick’s resident consulting taco expert. You will be our official eyes and ears for all things tacos,” reads one of the best job descriptions I’ve ever seen. “The ultimate responsibility for the Director of Taco Relations is to bring together and unify all taco lovers, young and old, in the name of tacos!” (A well seasoned democracy is a strong democracy, I suppose.) To get this four-month consulting gig, you need to submit a video pitch explaining how you’re going to think beyond the shell, how you’ll unite the warring tribes of hard and soft fundamentalists, and how you will make Taco TikTok a real and trending phenomenon. Your reward? Up to $25,000 a month and “taco immersion (and eating) sessions” at McCormick HQ in Hunt Valley, Maryland. If I still had my teenage metabolism, I'd consider a career change.

The temp job is real enough, but also another example of how social media is shaping the world. The Director of Taco Relations is already a viral hit, having earned McCormick plenty of coverage, from The Today Show to local media outlets across the country. And the lucky winner of this foodie sweepstakes will spend a lot of time using their “excellent storytelling skills, including through video and social media.” Shaping the taco narrative in a way that favors prepackaged flavors, so to speak. Influencing people is big business, whether you’re working as a journalist, a lobbyist, or the in-house taco enthusiast for a global spice conglomerate. Storytelling remains one of humanity’s oldest, most valuable art forms—occasionally it’s also one of the most delicious. —Stefanie Sanford

Ben McLeod/flickr

A view of the New Hampshire Union Leader newsroom at 1 a.m. in March 2007. Like many local newspapers, the Union Leader has faced cutbacks in the years since. But it's also still a going concern, rare among papers its size in 2021.

Black and Blue and Red All Over

Generally I find Axios and its news-reduced-to-bullet-points format exasperating. Is it a listicle? Is it a rough draft? Is it a primer? Tell me, Axios—tell me! But its approach is perfect for a piece published this week headlined "Journalism's two Americas." The state of the country's press—not just the "fake news" narratives, but also the escalating erosion of the nation's newspapers—has been covered a lot. But what Sara Fischer and Nicholas Johnston do in their Axios piece is boil this all down to the essentials: We're getting way too much national coverage and far too little local reporting. And while national-audience-focused outlets like CNN and CNET are getting infusions of investment, regional and local publications are being eviscerated. "The disparate fortunes skew what gets covered, elevating big national political stories at the expense of local, community-focused news," Fischer and Johnston write.

This might sound like an industry-specific problem: So what if a bunch of local reporters lose their jobs, or that publications are focused more on the country at large than their specific communities? But Axios makes clear why it should concern everyone, regardless of your feelings about the press, that there are fewer and fewer reporters working at fewer and fewer publications focused on cities and neighborhoods. Do we really just want coverage of whatever the Facebook and Google algorithms tell a bunch of publishers obsessively monitoring site traffic is important? But more to the point, a gutted press is bad for democracy. Corruption, graft, and abuses of power happen at all levels, regardless of political affiliation, and reporters are the check on breaches of public trust. (There's a reason the press is called the Fourth Estate.) And what happens to the fabric of our civic lives if we’re all living in and talking about a national ecosystem dominated by breathless and reactionary takes and influencer culture? (The Local Journalism Sustainability Act was recently introduced in the House of Representatives—with bipartisan support, which should tell you how important this is.) As a journalist who has worked at imploding legacy media brands, I've had a front row seat to this media mayhem. I've also probably guzzled too much from the spigot of this worsening story. And while Axios wasn’t here first—Margaret Sullivan’s slim book, Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy, is an excellent read—it does untangle much of this knotted tale. And thanks to their not-a-listicle-but-maybe format, you'll chew on it much longer than you'll spend reading it. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

U.S. Geological Survey/flickr

This bighead carp was collected on the Illinois River in 2014 to learn more about the anatomy and physiology of Asian carp, an invasive species decimating Lake Michigan's ecosystem.

HOMES is Where the Water Is

Not long after I dipped my toes into Lake Michigan for the first time last week, I picked up Dan Egan’s fantastic book on the history and ecology of the planet’s largest store of freshwater. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes looks at the ongoing fight over the future of these incomprehensibly huge bodies of water, and Egan resurfaces all kinds of strange and fascinating historical artifacts along the way. For instance: Did you know that two long-ago shipwrecks on the St. Clair River changed the water flow enough to raise Lakes Michigan and Huron by a few inches? Or that Chicago’s shipping canal effectively allows Great Lakes water to drain into the Gulf of Mexico, a massive manmade change to the continent’s geography? I didn’t! Or how about that there’s an invisible border, stretching across much of the U.S. and Canada, that determines who has the right to draw water from the lakes. “It’s based on the natural border of the Great Lakes watershed, defined as the landmass that drains into the lakes,” Egan writes, and it may become “one of the 21st century’s most contentious dividing lines, the manmade one that separates those who have access to the most expansive pool of freshwater on the planet, and those who do not.”

There have always been schemes to get Great Lakes water to drier places, but that invisible border, enshrined in law, keeps it from happening. Could there one day be a grand plan to tap Lake Michigan to supply an arridifying American Midwest and keep crops growing in the world’s breadbasket? It seems far-fetched, but Egan points to the ecological catastrophe of the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan, drained and destroyed through a decades-long Soviet effort to grow cotton in desert lands. As a megadrought in the American southwest strains some of the country’s largest reservoirs, it’s striking to encounter Egan’s tales of water wars past—not to mention the very human mistakes that led to them. —Eric Johnson

Washington State Department of Agriculture/Twitter

Mystery seeds sent from another country and listed on the packaging as jewelry? Where's that MiracleGro...?!

COVID and the Bad Seeds

The Great Seed Panic will likely be a footnote to the other horrors and traumas of 2020. But it was such a weird story—a bunch of people, all over the world, get weird random deliveries of seeds originating from in China; the recipients, cooped up in the first summer of the pandemic, duly take to social media to freak out and wax conspiratorial—that it felt like blessed, made-for-the-moment relief from everything else happening in the world. But just as quickly as it sprouted, it disappeared into the thresher of the internet and we all moved on. Except for Chris Heath, who a year later decided to finally get answers. The resulting feature, published by The Atlantic, is marvelous, with more twists than a barrel of pretzels. "I decided to reimmerse myself in the giddy anxiety of last summer," Heath writes. "I planned to speak with some of those who had received the packages, dissect the hullabaloo around them, and construct the definitive account of the seeds-from-China moral panic. It seemed straightforward enough. I had no idea." Honestly, like with any good mystery, the less you know about where this goes the better. I went in cold and found myself gasping and grinning and gawking at what should be in the running for all the National Magazine Awards. But for anyone needing a little more incentive, allow me to paraphrase Stefon: this story has everything—the USDA investigations unit, extreme gardeners, surly ranchers, ecommerce scams, exotic melons… The only thing missing is MTV’s Dan Cortez. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

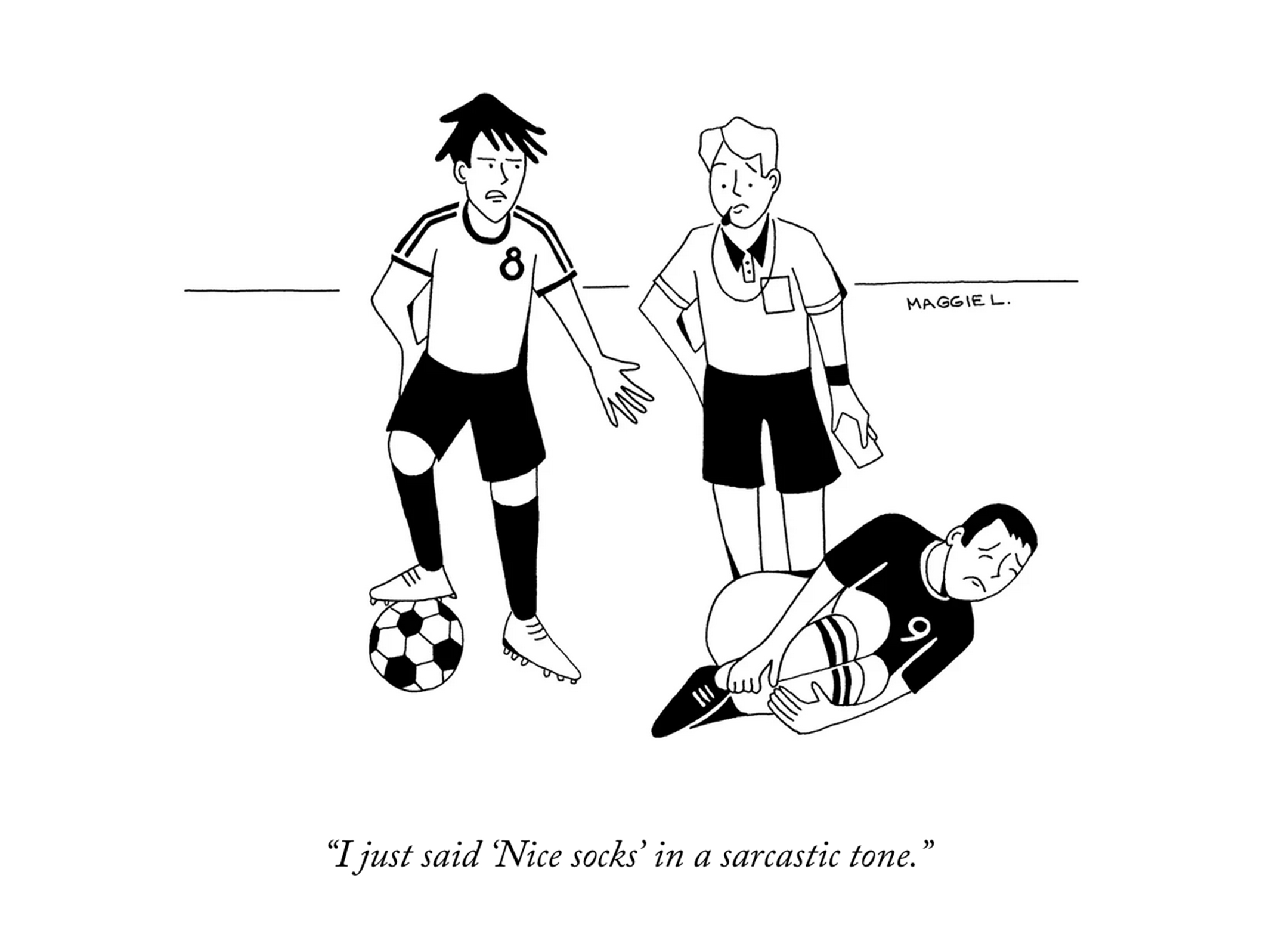

New Yorker

To quote one Jerome Seinfeld: "Now that's funny! Because it's real."

Foul Play

John Lanchester is a brilliant writer on just about any subject. His 2016 essay on cryptocurrency, “When Bitcoin Grows Up,” remains the best thing I’ve read on the rise of blockchain finance and the nature of money itself. So I picked up his latest piece on the role of cheating in sports with high expectations and wasn’t disappointed. On fake fouls in soccer: “Of the very, very many things that make fans cross, nothing makes them crosser than penalties and sendings-off induced by simulation. We all know what it looks like: the faintest contact with a defender sending the grizzled pro to writhe in agony on the pitch, one eye on the referee, the other on next year’s Oscars.” He then shares a very funny term for pretending to get fouled, delaying the game, and generally dancing around the edge of the written rules, but you need to read the piece to learn it. We can’t print here—this is a family-friendly zone.

Aside from teaching me a lot more than I wanted or needed to know about soccer, rugby, and cricket—Lanchester is British—this essay delves into the definition of cheating itself and how it can vary across sports and cultures. “The cheating I’m interested in involves the things you see happen while you are watching or playing a game that are against its rules but sometimes within its ethos.” Theatrical fakery is welcome in soccer but disdained in rugby, where players are supposed to be “primitive god-monsters.” Tampering with the ball has a long pastime in cricket (and American baseball) but strictly against the ethics of golf, so much so that players will narc on their own infractions. I’m still not going to sit down and watch a soccer, rugby, or cricket match any time soon—or ever, let’s be honest—but I’m always game for smart meditations on the meaning of foul play. —Eric Johnson