Interview

Teachers Aren’t Supposed to Talk Like That—Are They?

Educator and humorist Shannon Reed takes readers inside the complicated, challenging, and funny life of a teacher in her book Why Did I Get a B?

Students often wonder (and joke about) what their teachers are like outside the classroom: Are they as uptight at home as they are at school? What do they do on weekends? Do they even know what fun is? We tend to see teachers not as people but as, well, teachers—authority figures who only think about grades, lesson plans, and detention. That’s nonsense, of course. They’re real people. And if there’s any doubt about that, Shannon Reed explodes it in the second paragraph of her book, Why Did I Get a B?: And Other Mysteries We're Discussing in the Faculty Lounge.

“One of my students was one of the most horrible people I’ve ever met,” Reed writes in the preface. “I had already had to stop one of his peers from hitting him, even as I wished someone would hit him, and hard.”

This isn’t how teachers are supposed to talk. Are they even allowed to think about their students? But if there’s a through line holding Why Did I Get a B? together, it’s the argument that teachers are, first and foremost, people—complicated, dedicated, determined, and often funny people.

It’s a realization Reed came to after 20 years of working in classrooms, first as a Johnstown, Pennsylvania, preschool teacher, then in New York City at a Catholic high school (Queens) and at an underfunded public theater arts high school (Brooklyn). Now she’s a visiting lecturer in the writing program at the University of Pittsburgh. Reed comes from a family of teachers but entered the profession by accident as she worked on establishing a theater career. She documents her unpredictable journey as an educator in Why Did I Get a B? through a series of honest, bracing, and self-effacing personal essays. They’re broken up by humor pieces she has contributed to publications like McSweeney’s, The New Yorker, and The Paris Review. The result is a book that offers a unique perspective on teaching, by turns eye-opening and irreverent.

Reed spoke to The Elective about her classroom career, how to find your voice as a humor writer, and the one thing every student and parent needs to know about teachers.

Heather Kresge (author), Simon & Schuster (cover)

Why Did I Get a B? is about your journey as a teacher, but it also contains a lot of stand-alone pieces, like lists and essays. Why write this kind of book?

It reflects who I am as a writer. I write plays, and there are some little plays in the book. I write humor, and there's humor in the book. I write personal essays, and there are personal essays in the book. I write polemics sometimes, and there are a few of those in the book as well. As a reader, I like when there's variety in a book. It's more a collage than it is a straightforward, novelistic look at something. I think that's fun and different.

But I also felt that it reflected what teaching is like. There are so many days when I'd show up to school in a great mood or a terrible mood. Then just one interaction with a student or colleague would completely reverse that. Now I'm in a terrible mood! Now I'm in a great mood! Then class would happen, and I’d feel that I’d done a terrible job with that class and I didn't teach them anything and I'd be despondent. But then the next class would come in. We’d have a great time. Someone would make a hilarious joke, and I’d go into my lunch period in a great mood. That constancy of change is what I think of as the undergarment, the girdle of teaching—you don't know what's going to happen.

Do you ever find yourself going into teacher mode when you're out of the classroom?

I think about that quite a lot. The first high school I taught at, Stella Maris, which I write about in the book, I noticed that there were teachers who couldn’t stop being teachers. Their voice was the same whether they were talking to me or they were talking to a student, and it was always super-aggressive. Just a bossy way of going through life. I didn’t want to be like that. I knew right away that I didn't want to be talking to my friends or my family or even a clerk at the drugstore in that voice, with that attitude. But I also realized that I didn't want to talk to my students that way either. So rather than trying not to be a teacher with my friends and family or random strangers, I try not to use a super-teacher voice or be bossy in my classroom. I don't need to constantly assert that I'm in charge. That’s not a good vibe in the classroom. I’d rather welcome other people's voices and hear what they have to say and have them listen to each other and sort out things vocally and in their writing. And to feel comfortable sharing that work with me.

You write a bit about how, at the beginning of your career, you saw two kinds of teachers: terrors and martyrs. How has that view changed?

I was totally wrong. I've met so many dynamic, exciting, interesting teachers who are truly motivated by wanting to help their students and who still feel a lot of passion about being in the classroom. Especially at the college level, people are able to continue to develop as artists or engineers or doctors or whatever else it is that they're doing while also being excited about sharing their knowledge and their growth with their students. That's not something I’d anticipated when I stumbled into teaching, and I love that about it.

Teachers are constantly bumping up against cultural ideas about them. One of those is that a good teacher is somebody who works 12 hours a day, will do anything for their students, and has no life outside of teaching. That's a damaging portrait in several ways, and it doesn't really serve the students well either. I've seen students come to Pitt and find it quite shocking that teachers aren’t there to facilitate them. But I think where it maybe is most dangerous is that it tells people who might want to be teachers and might be wonderful teachers that this isn’t the job for them unless they want to martyr themselves. And quite understandably, many people don’t want to martyr themselves.

From the outside looking in, teaching doesn't seem to come with a lot of rewards. You're not going to make a ton of money. You’re not going to get super famous. Things you look for in a job when you're 18, 20, or 22 don't seem to be there with teaching, and you're supposed to give so much of yourself. That's not very alluring, and I understand that. That’s too bad. We’d probably be better off if we allowed teachers to be full people who also teach, not demand that they only be teachers. That's a path to burnout.

McSweeney's

Screenshot of an article written by Shannon Reed, which was the most-read piece on the McSweeney's webiste in 2018.

You write that you vowed early on that you wouldn’t be one of those people who work 80 hours a week, that you'd have a full, rich life. How difficult was it to achieve that goal?

It was impossible when I was teaching public high school. I was constantly asked—everyone was—to do more and more and more that we just couldn’t do. There weren’t enough hours in the day. I ended up leaving. I j couldn't teach high school anymore. When I went to Pitt, I saw it as a way to transition into something else. As I say in the book, I didn’t come to Pitt thinking "Oh, yay, now I'll become a college professor!" I came to Pitt thinking "Great. I get a full ride and I get to write for three years and then I will figure out what happens after that." I was lucky that I got to teach as part of my scholarship. I love teaching at Pitt. It healed that part of me. We work very hard as professors, but we have a longer summer. It’s teaching three classes a week instead of five classes a day. All of that has allowed me to do more things than just teaching.

Were you writing at all while you were a high school teacher?

I’d write when I was teaching at Stella Maris. I was a playwright, and I had productions of my work in New York, off-off-off Broadway. When I went to the public theater arts high school (that in the book I call THSB), I did write but not nearly as much. I found it incredibly frustrating because my work would get produced, but it was often 8 o'clock at night. I had to get up at five in the morning to get to work so I couldn't go to the show. I did write, but it was … What’s that expression? Like getting blood from a stone. It was hard.

How did you find your voice as a writer? McSweeney’s, for example, has a distinctive register not everyone can hit.

A lot of my humor writing voice comes from my work as a playwright. I wrote mostly comedies, which stems from a kind of cynical worldview. McSweeney's does have a distinctive style, but every place has a distinctive style. One of the best things I learned at the MFA program is to pay attention to what kind of style a publisher prefers and then try to write in that style. That seems obvious, but people don't think about it. They write what they want to write and hope somebody takes it. When I decided I wanted to get into McSweeney's, I started reading their pieces and accepted that I was going to get rejections there until I hit that voice correctly. My work has been published in The New Yorker too, but I started reading The New Yorker when I was 14 years old. That style is inside me. I understand what they're looking for.

Much of it is brevity and revising—boring! When I teach humor writing, my students always say, "What? Brevity? Revising? That's not fun." I always say, "If you want to have fun, you should probably go work in a writers’ room for a TV show." I don't mean that sarcastically. That’ll be a place where you can rat-a-tat-tat your ideas and work on them with other people. That'll be super fun. Writing humor that's meant to be read requires brevity and revising. A single word choice can make the difference. Where that word is in the sentence can make a difference. That’s boring work. It's a very English teacher sort of thing to write, in a way, because it’s so much about word choice and grammar and spacing and all that.

The Paris Review

You've mentioned your theater training a few times, and you write about the on-public-display quality of teaching. Does being comfortable on stage make you a better teacher?

I don't know if that makes me a better teacher. It’s been helpful to be able to think about performance and what performance can do and how performance can manipulate people and move them from one place to another. Any reflective teacher can figure that out. I was already thinking about the nature of performance when I started teaching so it was useful.

Our culture is very cruel about aging. That’s hard for teachers who started young and fit a cultural ideal of what attractiveness was when they were younger. They didn’t realize how much that was part of what was affecting their students. As they move away from what’s an unacceptable cultural ideal into being a middle-aged person or an older person, they no longer have that sway over their students. That can be incredibly painful. It reinforces that feeling of becoming obsolete or not important or not worth listening to anymore. I don't think that's the teacher's fault. I don't know how to fix that problem because I can't fix our culture. But I have seen that happen a number of times, and it's regrettable. Our older and experienced teachers have the most to teach all of us. (Even younger teachers can begin to feel disengaged.) I hate when they feel they aren't being given the attention and the respect they deserve because they don't have that performative hold over their class anymore.

You mentioned burnout. How much of that change in confidence is attributable to burnout? If you don't have time for anything else, if you make it to 20 years or more as a teacher in public high school, I imagine that will grind you down to some kind of nub.

I think so. It’s hard to try to reach an audience that isn't engaged by you—doesn't want to be there—over and over. That's hard no matter what the field is, and that's what we ask longtime teachers to do. I don't think this statistic is necessarily true, but when I started teaching at the public school in Brooklyn, one of the longtime teachers said, "If you have 30% of your class engaged, you're doing great." I thought to myself, "That's not half!" As a theater person, I don't need to have everyone fascinated, but I want most of the audience paying attention to me while I’m performing. Maybe that's not the best attitude toward it. But I did feel that way.

Every longtime teacher I talk with—people five years from retirement or even two—they would talk about the burnout they felt. But I also saw every single one of them be engaged by students who really wanted to learn. That still got them. Nobody truly, entirely burns out—or maybe not as many people as we think do.

Will having this writing career will help you to get to year 20 or year 30 and still feel energized by the job?

I hope so. I just finished year 20. I thrive on variety. It’s helpful for me to change up classes every semester, to get new students, to be in a different room. I see that with teaching at the college level in a way that wasn't there for high school or preschool teaching. There's not the same monotony, and that's beneficial. It’s not true for all teachers. Many people love having their own room and having it set up exactly the way they want. But that was not true for me. I enjoy the variety and the change.

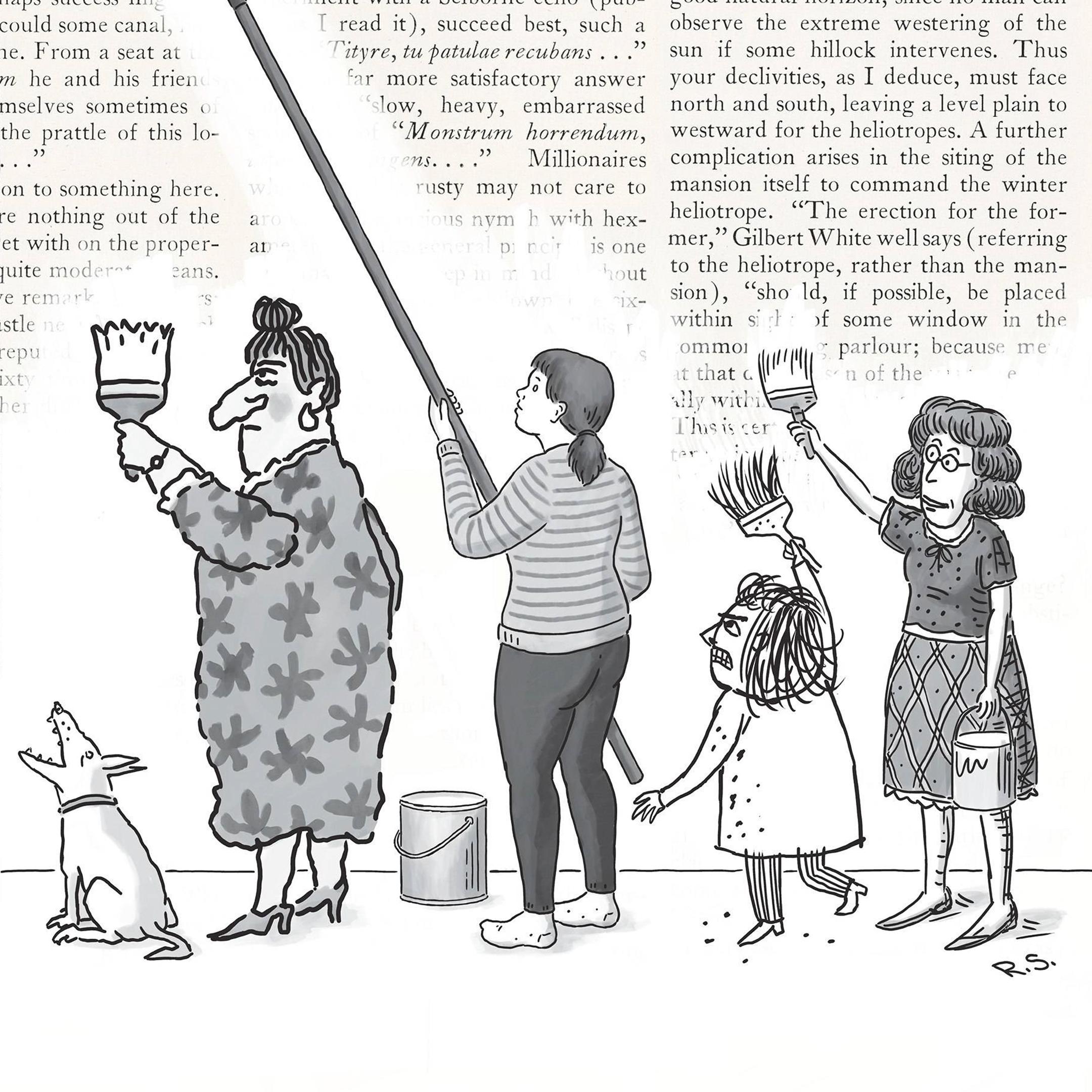

The New Yorker

What's one thing students and parents would be surprised to hear about teachers?

How much teaching shapes a person. I make a joke, I think in the acknowledgments, about teacher friends and how before I was a teacher, I thought, "Why do all the teachers hang out together?" And now I think, "Oh, I understand." Being a teacher profoundly affects how you live your life. If you're teaching high school, you're usually getting up very early and going to bed very early, which means you're not watching late-night television. You don't get that joke and you're not hanging out with other adults who are staying up until midnight, except maybe on the weekend. That’s a small example, but the teaching schedule shapes who teachers are. I find that interesting. People don’t think too much about that.

What's one thing students and parents need to hear about teachers?

That teachers are human. Many, many teachers are in the job because of a profound love for teaching and for working with young people. But that passion cannot sustain perfection. We're still people, and we still mess things up. We still get sick. We're still tired. Our hearts are broken. We get bad news. A text comes in that upsets us. We can’t be perfect all the time. It's not possible. We deserve second chances.

When I forget a student's name, it's like a knife in my heart. I see in their eyes that they're thinking, "Oh, God! She doesn't even know who I am!" If I can go to that student and say, "I'm so sorry. I didn't sleep well last night… " (I'm now talking to college students, so they get it.) But the grace of being able to say something like "Oh, it's okay. Don't worry about it. You'll get my name right next time" is a real gift that you can give to a teacher and a nice moment of connection.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.