Profile

The "Grand Opportunity" of AP African American Studies

For senior program manager Dr. Brandi Waters, working on the course is necessary, meaningful—and personal

For Dr. Brandi Waters, an in-depth look at African American history and culture didn’t come until late in high school—and it took a special summer program to make it happen.

“My guidance counselor nominated me for a scholarship I’d never heard of, offering the chance to take an African American Studies class on a college campus,” Waters recalls. “I had just assumed there were certain things you couldn’t know about Black people or the past—things that were just lost to history. It was a huge gap in the regular high school curriculum.”

The experience resonates even more today. Waters is the senior program manager for Advanced Placement African American Studies. The role finds her supervising the development and rollout of the nation’s first African American Studies course to be widely available to high school students.

It’s an effort to close the curriculum gap Waters experienced as a student—ensuring the next generation of students can access a rich and inspiring encounter with Black history and culture.

“This work is personal for me,” Waters says. “I think about what I would have wanted and needed as a high schooler, and I see so much of that in this course.”

Waters attended a public high school in rural New Jersey before earning her bachelor’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania, then a doctorate from Yale. She was always a committed student—“a true-and-true nerd,” as she put it—but also had broad cultural interests. She was a varsity cheerleader who loved going to football games, as well as a devoted reader of Latin American literature thanks to her AP Spanish teacher.

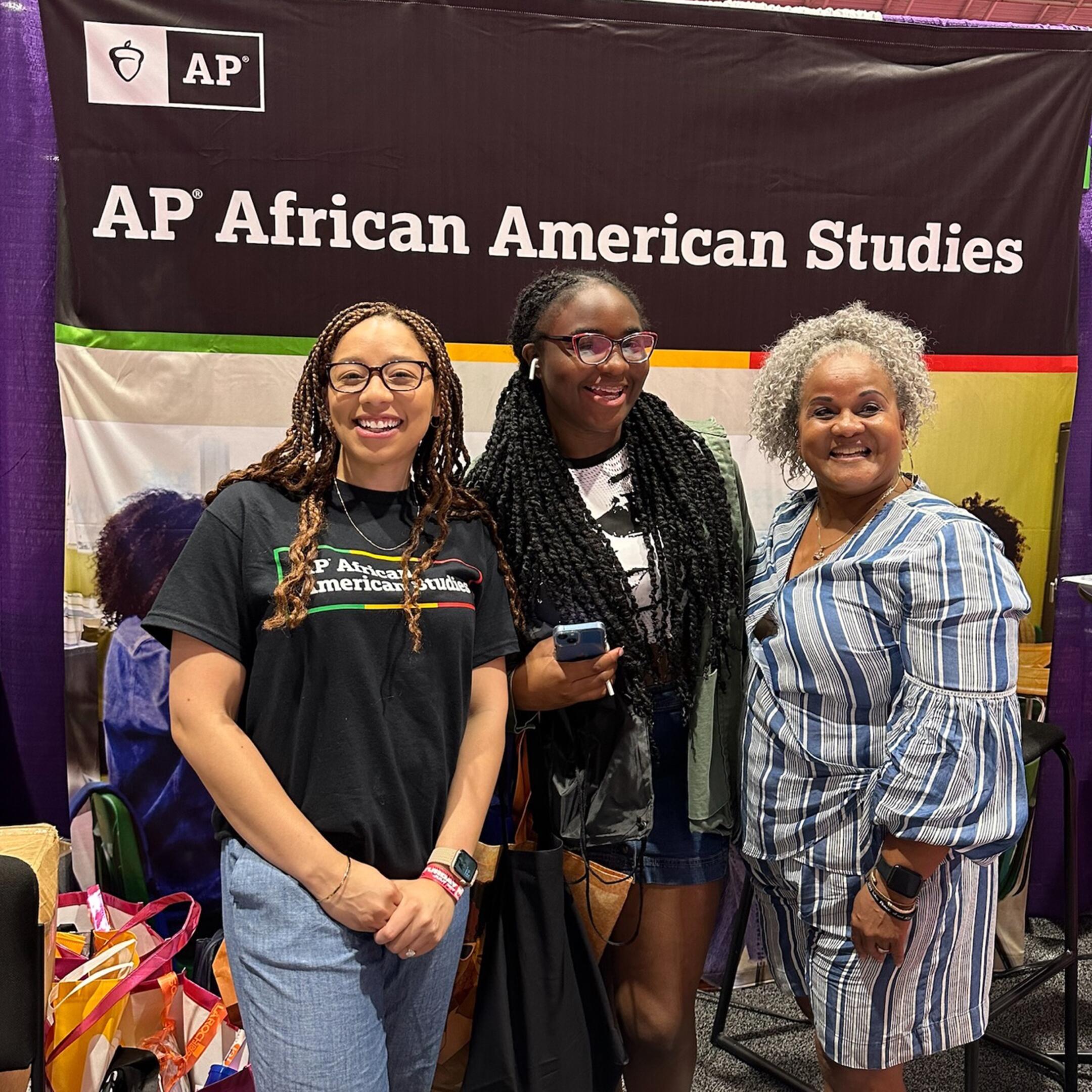

Dr. Brandi Waters speaks with an AP African American Studies pilot student in Baltimore. “This work is personal for me,” Waters says.

The ability to navigate diverse social groups was important to Waters, and she valued classes that introduced new ideas and cultures. “I was blessed with consistently good and thoughtful teachers,” she says. “I loved their commitment to exposing students to new worlds and convincing us to take chances we didn’t know we could.”

The guidance counselor who convinced Waters to take a chance on the African American Studies summer program certainly made an impact. The early exposure to college-level African American Studies changed Waters’ life in a profound way. It convinced her to take more Black Studies classes in college, and she decided to pursue both African American and Latin American Studies during her undergraduate years at Penn. Her introductory course was with the famed author and professor Michael Eric Dyson, who took students on a whirlwind tour of history, law, culture, and explorations of the Black diaspora.

“I was just astounded,” Waters says. “I saw that Black people live everywhere, they’ve always been everywhere, they speak all the languages, they have distinctive art, history, literature, everything! From that point on, it just consumed me.”

Her professors noticed Waters’ devotion to the discipline, and legendary scholar Herman Beavers encouraged her to become a professor. “It was a new thought,” Waters says. “I hadn’t encountered many Black faculty until I went to Penn. I never thought that was something I could do.”

At Penn, Waters combined her interests with a thesis on beauty standards and the representation of Black women in Colombia. The paper delved into profound issues of race and culture by focusing on the first Black winner of the Miss Colombia pageant, Vanessa Mendoza. Waters traveled to Colombia, pored through local archives, met with anthropologists, and conducted hours of field interviews.

“It was a fascinating process, and I learned so much from being there,” she says. “‘Black’ is not a singular term in Colombia. There are all these different kinds of communities, identified in different ways. It made me ask new questions about the position of African Americans in the U.S. and to wonder what opportunities we might open up when Black communities embrace all of their diversity.”

"I think about what I would have wanted and needed as a high schooler, and I see so much of that in this course."

After earning her doctorate, Waters gave serious thought to becoming a professor, and still relishes the idea of returning to campus life one day. But the chance to build an entirely new AP course for College Board—to play an outsize role in shaping the way thousands of students will encounter African American Studies for the first time—was too meaningful to pass up. She also gets to work alongside distinguished scholars from across the country who have given time and expertise to help develop the course.

“When an opportunity like that comes up, you have to seize it,” Waters says. “It’s a chance to share the best of what I’ve learned, to curate all of these fantastic resources that most people don’t know exist and put all of that in front of a much larger audience of students. It will equip students with that extra lens so much earlier.”

Waters often thinks about the advice she received from renowned historian and musicologist Daphne Brooks, who was one of her professors at Yale. Brooks is known for her work on race, gender, music, and culture, exploring everything from slave narratives to the musical legacy of Prince. Brooks offered a bracing question that helps guide Waters’ decisions to this day: “In the work that you’re doing, who is becoming free?”

“Who is gaining more freedom?” Waters says. “It’s not just about ourselves and our personal interests. You always have to remember the larger picture of why this field of African American Studies exists. It’s a methodology for appreciating cultures and the human experience more broadly, for encouraging students to think in a more capacious and inclusive way.”

The AP African American Studies course is interdisciplinary and wide-ranging, covering everything from ancient African kingdoms to thoroughly modern issues in American culture. For students and educators already engaged in the course in pilot classrooms, it can be hard to pick a single favorite topic.

AP African American Studies is "a chance to share the best of what I’ve learned, to curate all of these fantastic resources that most people don’t know exist and...equip students with that extra lens so much earlier.”

That’s true for Waters, too. But some of her favorite course content centers on post-emancipation Black life in America, the stories of how the first generation of African Americans to come of age after the Civil War thought about citizenship and freedom.

“Understanding the many different ways Black people envisioned and reached for their freedom is really important,” she says. “There are so many things we’ve been taught about that era that are just wrong, and I think it’s crucial to go back and get the foundations right.”

Waters had very few AP courses available to her in high school. And despite the college summer program, she had to wait until arriving at Penn as an undergraduate before getting a deep look at African American Studies. Knowing that so many students will now have that experience in high school through AP African American Studies is thrilling, and well worth the intensive effort of the last few years.

“There’s a lot to traverse, but the opportunity is so grand. That’s what keeps me committed and focused,” Waters says. “There’s so much richness in this course. All of it is beautiful, complex, and worthy of study.”