Interview

Mirrors, Windows, and Reconstructing Black Education

Kaya Henderson, cofounder and CEO of Reconstruction, is creating the spaces for learning and engagement that Black students need

Kaya Henderson is one of the most admired school leaders in America. It’s a reputation earned through her three decades working in schools, as a policymaker, and for major nonprofits. For six years, she served as chancellor of Washington D.C.’s public schools. When she left the system in Fall 2016, her legacy included growing enrollment, major gains in reading and math performance, and wider access to advanced courses for all students.

Today, Henderson is chief executive officer, and cofounder with Dr. Roland Fryer of Harvard University, of Reconstruction, a technology company delivering “unapologetically Black” coursework to students and families outside of the normal school setting. “We wanted to create an environment that feels different than school, that doesn’t look like school,” she tells The Elective. “We don’t call our classes math and reading. Instead, we have book clubs, we have Black Shakespeare, we have a course on HBCU sports statistics. Young people get hyped about learning sports, and they master the fifth-grade math principles.”

Reconstruction is driven by Henderson’s belief that education happens well beyond school walls, and that Black children need access to cultural content just as much as they need core academic classes. “This my 30th year in education, and I’ve had the blessing of seeing the education challenge from the classroom to the superintendency,” Henderson says. “What I’ve learned is that education transformation is possible, but the current systems and structures are woefully outdated and inadequate. We have to reimagine education if we’re going to build strong, whole children.”

Henderson recently spoke to The Elective about the mission of Reconstruction, what it means for education to be “unapologetically Black,” and giving Black students the tools to access their history and culture. I’ve known her for years—she occasionally shares vegetables from her backyard garden—and I was excited to hear her vision and why students need both “mirrors and windows” to be successful. “I think we have to empower Black families and Black institutions,” she told me. “It’s about rebuilding our cultural and civic institutions, and our parental power.”

Reconstruction

In 2020, you launched this new project, Reconstruction, aimed at reaching Black students and Black families outside the normal school day. Why?

Reconstruction was created to provide unapologetically Black content and classes to young people, their families, and their communities. Courses around Black history, Black culture, Black literature, Black art. A lot of this comes directly out of my experience in D.C. schools. When we built a curriculum, one of our priorities was ensuring what we called “windows and mirrors”—that our kids see both themselves and their communities reflected in what they’re learning, which is the mirrors part, and get to see windows into communities where they might not otherwise go.

When kids see themselves in what they’re learning, their engagement and confidence increases. When I saw so many kids who were previously nonplussed about what they were learning suddenly get deeply engaged when the classes and the content reflected their own community, I wanted to create more of that. When we give kids things worthy of their time and attention, they’ll work harder, they’ll perform above and beyond. And I want Black students to have that not just in February, during Black History Month, but all the time.

We are asking critical questions in a Socratic seminar. We are engaging kids deeply in book clubs. We are interrogating classics like Shakespeare and helping young people understand their job is to question. We are empowering young people to understand it is their responsibility to not just ingest information, but to actually analyze and think critically about it. That’s a core part of the way we do our work.

We are grabbing onto the intellectual traditions of African American people. We are harkening back to Citizenship Schools and Freedom Schools and literary salons. I want all of our students to know that Black people have been seeking intellectual freedom and academic excellence since we got here.

What does it mean to be “unapologetically Black” in your content and outlook?

I find that when Black people like me want to focus on our own history and culture, we have gotten pushback about why we’re not being more universal and diverse. People say, “This feeds separatism, this breeds tribalism, this is divisive.” But I am unapologetic about my focus on African American kids for a number of reasons, but first of all because in my 30 years of education, it has been clear that those are the children most at risk. Society has told our children that they’re lazy, they’re not worthy, that they’re not as smart. And I am unapologetic about pushing back against that to create a strong vision of Black identity.

I am unapologetic about Reconstruction in the same way that Jewish people are unapologetic about Hebrew school, in the same way that Chinese families are unapologetic about Chinese school for their kids. I don’t think it’s divisive to be intentional about the identity development of their young people. If we build children with a strong Black identity, then they can appropriately engage with children of all backgrounds and identities.

There’s a quote I love that’s often attributed to Frederick Douglass: “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” And to me, that’s the unapologetic part. I am building strong Black children. Those are my children, and that is the need I see in the world.

“Reconstruction” is such an interesting name, calling to mind this era of American history after the Civil War that is often taught as a time of failure for the country, when the progress of Black Americans was cut short.

We believe that by teaching history, we can empower the next generation to lead in a different way. So we harken back to the Reconstruction era when we started 5,000 community schools, founded 37 historically Black colleges and universities all across the country, incorporated our own banks, towns, and farming communities, started our own businesses. It was an era when we sent our first Black senators to Congress and elected Black lawmakers to state legislatures across the South.

It was extraordinary, and it is one of the least-taught periods of American history. When it is taught, it’s often portrayed as a failed era. But we see it as an incredible success, and we need to teach our young people that we have been successful here. In the first 12 years after the Civil War, left to our own devices, we did all this. When other people saw that success is when you see the rise of Black codes, Jim Crow, and the Ku Klux Klan.

We also believe that what we’re doing is about reconstructing the Black community. We’re helping rebuild families, civic institutions, and Black cultural traditions. I’m worried about who’s minding the cultural store for Black people. We have a course where we teach spades, which is so much a part of family tradition in Black communities. Spades is fun and cultural, but it’s also strategy and math. So are dominoes and bid whist—all these games of our culture that our young people often don’t learn anymore.

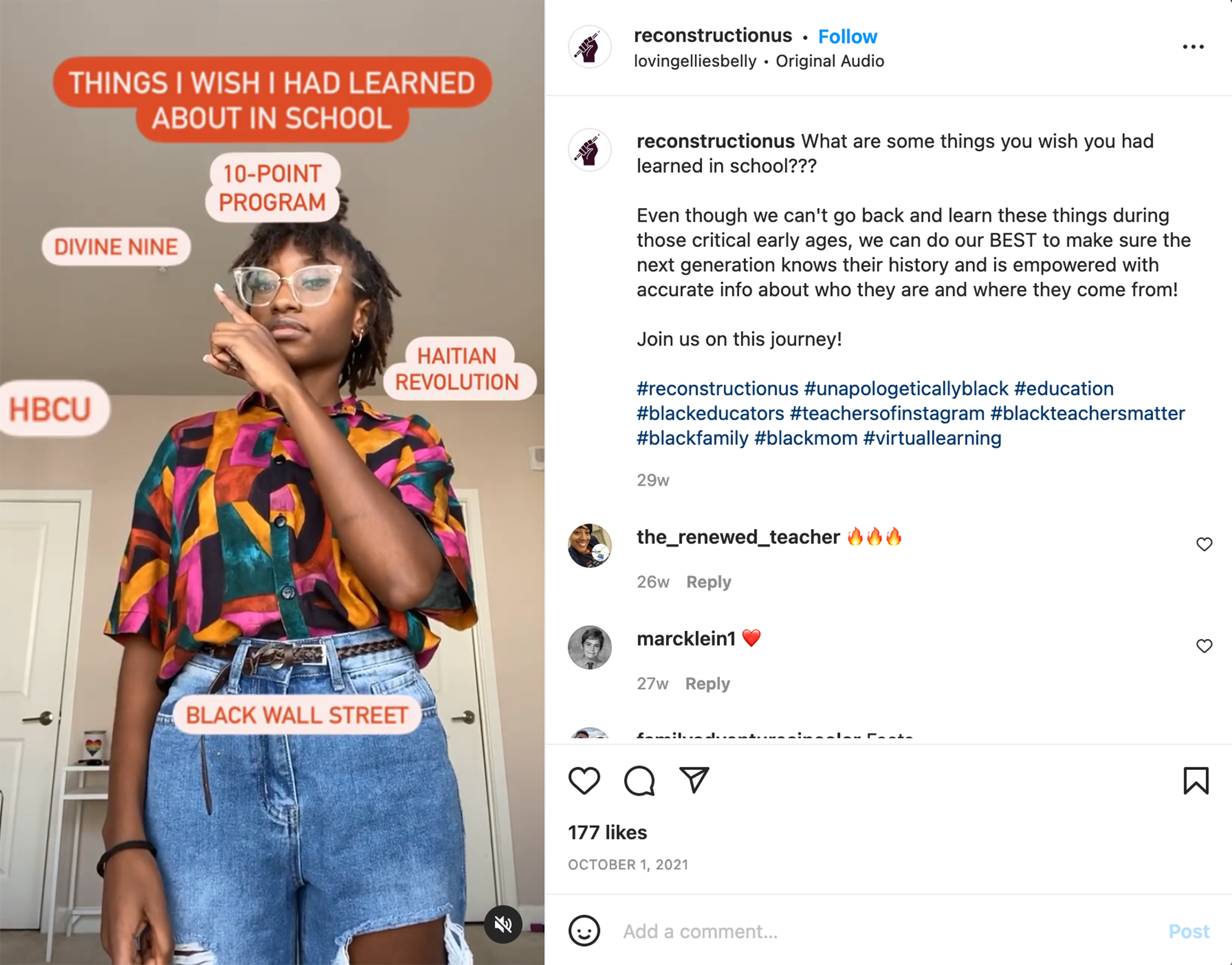

Click on the image to see Reconstruction's Instagram video.

A lot of Black young people don’t live with their extended families, so they don’t learn these traditions. They don’t learn how to cook macaroni and cheese or learn why we eat Hoppin’ John at New Year’s, and we need to teach our kids not only how to cook these dishes but the history of these dishes. We have a course called Cooking for the Soul, where you learn how these foods got here and why we eat them. You see that there are historical threads to pull in all of these things.

I want Black children to understand their history, and to understand that our story is more complex than what they’ve been taught about us. We have been told this narrative even in our culinary traditions that we made do with scraps, that we turned scraps into delicacies, and part of that is true. But in fact, when you look at where gumbo comes from for real, these weren’t scraps! Maybe society thought they were, but our ancestors knew these were foods rich in vitamins and nutrients.

I want that reweaving of the narrative, to understand that the story looks different depending on who is telling it. I want kids to see that there is a dominant narrative out there, in schools and in the world, that does not necessarily reflect the reality of Black Americans and their history. I want them to think, “What do we do together about that?

I want to go back to your observation about mirrors and windows. We’ve talked a lot about why holding up a mirror is important, but can you explain the window part of that approach?

This sounds sort of simple, but I think we need treat the young people we serve in our schools the same way we treat the young people in our own homes. You want your kid to study abroad, you want your kid to play a musical instrument, you want your kid to learn about the world. You’re not just drilling them in math and reading all day. Even if your kid is a struggling reader, you’re still going to let them play a sport, go on vacation, everything you can do to widen their world.

At the same time, in schools, what we do with struggling students of color is narrow that world. We say, “We’re just going to drill and kill on this reading and math,” and we think that is somehow or another going to prepare kids for something bigger and better and beyond? We try to remediate kids to death, when what we need to do is inspire kids to greatness.

Those struggling, low-income kids need to go abroad more than your kids or my kids need to go abroad. They need music lessons more than your kids or my kids need music lessons. I want to see music and art and foreign language and PE class and full libraries in every elementary school. I want to see study abroad programs for the kids who have barely ever been out of their own neighborhoods. That’s how you widen the aperture—that’s how you inspire kids.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.