In Our Feeds

Celebrating Perseverance, Reinventing Microchips, and Investigating Sneezes: Five Things That Made Us Smarter This Week

From steep declines to steep climbs, we learned a lot over the last seven days

We’re living in a world awash with content—from must-read articles and binge-worthy shows to epic tweetstorms and viral TikToks and all sorts of clickbait in between. The Elective is here to help cut through the noise. Each week, members of the Elective team share the books, articles, documentaries, podcasts, and experiences that not only made them smarter but also changed how they see the world around them and, often, how they see themselves.

Michael Hanson/Getty Images

We all run our own race. And it's a marathon not a sprint. But there are big rewards for those who push through to the finish line.

2 Legit 2 Quit

I'm hesitant to ever claim that a Tweet made me smarter—I am firmly in the camp that believes Twitter is ruining civilization—but I can't deny the concise brilliance of this missive from historian Charles McKinney, Jr.:

Dr. McKinney so perfectly captures a critical point about education: you're never done, and one moment in time does not define your long-range potential. You don't have to ace this test, or this paper, or this class. You just have to keep working at it. You can get a 2 in APUSH and still go on to be a fantastically accomplished scholar, or you can fail freshman biochemistry and still go on to become a genius medical researcher. It's not easy, and someone like Dr. McKinney spent years working toward the credentials he lists in this tweet. There are almost always setbacks on a path that long, but that's not the same thing as failure. Millions of students will be getting AP scores back in the coming weeks, and some of them are inevitably going to feel disappointed with the scores they see. That's fine—as long as they remember that it's not the end of the story. Thanks, Dr. McKinney, for making that point so well. —Eric Johnson

John T. Bledsoe/Library of Congress

A group protesting admission of the Little Rock Nine to Central High School in 1959. The facts of this moment in American history—some White people tried stopping Black students from going to school—are indisputable. How it's taught? That's thornier.

Rough Draft of History's Uncertain Future

In another life, I’m a historian. I always loved history, and in college I had taken enough courses to realistically double-major in history while completing my BA in film studies (sheesh). I never completed the history degree because of some dumb point of pride about how the senior seminar was being run, so the best I can claim to be is an amateur historian. But as my groaning bookshelf can attest, I more than made up for dropping that final requirement in the amount of history I’ve read over the next 17 years. So naturally I’ve followed the escalating culture war over American history education, which has erupted in the wake of the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol, with confusion and dismay. But as fronts in culture wars tend to be, this was slippery and always seemed about more than “critical race theory” and the inability of its critics to actually define it. I couldn’t find my footing on it—until, that is, I read Timothy Snyder’s brilliant piece in last week’s The New York Times Magazine, “The War on History Is a War on Democracy”, and his framing of the issue around memory laws.

It’s a concept I hadn’t encountered before and that Snyder, an author and a history professor at Yale University, describes as “government actions designed to guide public interpretation of the past. Such measures work by asserting a mandatory view of historical events, by forbidding the discussion of historical facts or interpretations or by providing vague guidelines that lead to self-censorship.” He spends nearly 2,000 words explaining how Stalin used memory laws to obfuscate the genocidal implications of the Soviet Union’s 1932 famine, then gloss over the USSR’s allying with Hitler at the start of World War II, and how Putin weaponized the long-tail of memory created by those memory laws to justify invading Ukraine in 2014. And after a brief discussion of President Trump’s ill-advised 1776 Project, Snyder lands the gut punch: “This spring, memory laws arrived in America.” What follows is an impassioned yet surgical vivisection of recently-passed legislation in numerous states limiting what students learn and how they engage with American history, particularly around race. But the real power here is his on-the-ground experience as a history teacher. He knows history can be challenging—especially for certain people, depending on the lesson. But that’s the point: “My experience as a historian of mass killing tells me that everything worth knowing is discomfiting; my experience as a teacher tells me that the process is worth it. Trying to shield young people from guilt prevents them from seeing history for what it was and becoming the citizens that they might be. Part of becoming an adult is seeing your life in its broader settings. Only that process enables a sense of responsibility that, in its turn, activates thought about the future.”

Headlines about “history wars” and “critical race theory” are good for hate-read clickbait, but much of it obfuscates the harm this will cause America’s students—and the implications that has for the nation’s future. “Democracy requires individual responsibility, which is impossible without critical history.” Agree or disagree, Snyder’s piece is bracing and worth your time. —Dante A. Ciampaglia

Colin Hawkins/Getty Images

What causes us to sneeze? In this woman's case, gonna go out on a limb and say "pollen allergy."

I Feel the Need—The Need. To Sneeze!

It’s a big world out there. And if you ever doubt it, just check out some of the scientific institutes that exist in universities across the country. Washington University in St. Louis has a Center for the Study of Itch and Sensory Disorders, which I know because they published this marvelous primer on why humans sneeze. For all the advances of modern medicine, it turns out we still have a lot to learn when it comes to the achoo sciences. “Sneezing is the most forceful and common way to spread infectious droplets from respiratory infections,” the article notes. “Scientists first identified a sneeze-evoking region in the central nervous system more than 20 years ago, but little has been understood regarding how the sneeze reflex works at the cellular and molecular level.” This matters for a lot of reasons. Millions of people suffer from seasonal allergies, me included, and we’ve all learned over the last year just how big of a role sneezing can play in spreading disease. “A sneeze can create 20,000 virus-containing droplets that can stay in the air for up to 10 minutes,” explains Dr. Qin Liu, associate professor of anesthesiology and the lead sneeze sleuth at Wash U. “By contrast, a cough produces closer to 3,000 droplets, or about the same number produced by talking for a few minutes.”

So sneezing is serious business. But also very funny, as evidenced by the iconic baby panda sneeze video on YouTube, which has been viewed close to 5 million times and still makes me laugh every time I see it. Even babies think sneezing is funny! (Or they just appreciate the effort at humor, according to experts). Best I can tell, there is no academic institute devoted to sneezing gags—at least not yet. So many mysteries left to unpack. — Stefanie Sanford

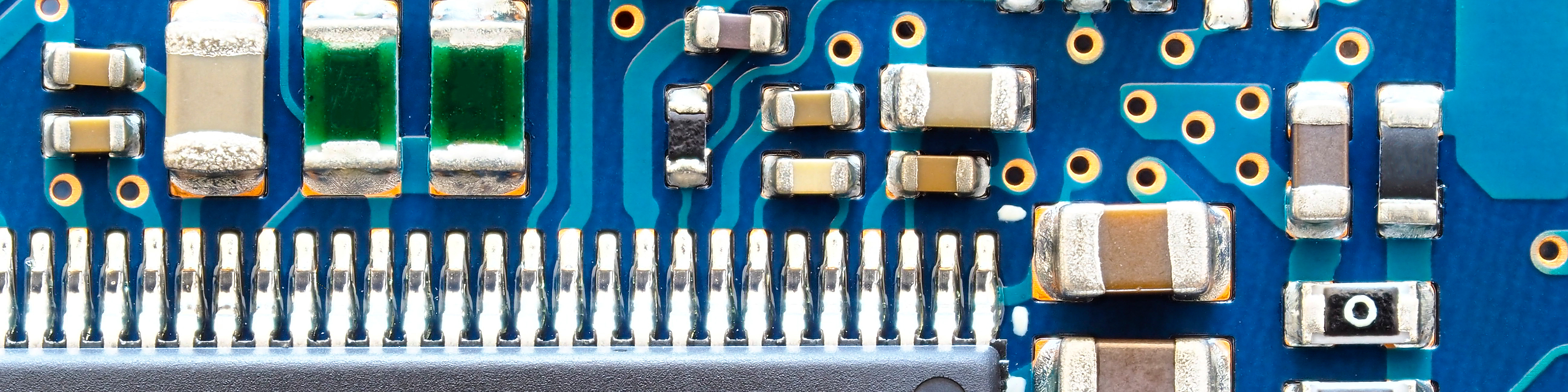

Jose A. Bernat Bacete/Getty Images

Microchip? More like majorheadache, amirite?

Chips Ahoy!

The modern world runs on computer chips—Silicon Valley got its name as a hub for manufacturing silicon semiconductors—and they’re some of the most complex objects in the world to make. Building an advanced semiconductor plant can mean tens of billions of dollars in initial investment with construction running the better part of a decade. The most advanced chips are only built in a handful of countries, mostly in East Asia, and the raw materials to make those facilities run are also highly limited. That has made these tiny chips a major bottleneck in the global economy and a huge issue in international relations, as Andrew Blum details in this excellent piece for Time magazine. “Microchips, long revered as the brains of modern society, have become its biggest headache,” Blum writes. “Because chips are a crucial component of so many strategic technologies—from renewable energy and artificial intelligence to robots and cybersecurity—their manufacturing has become a geopolitical thorn.” (A shortage has also meant a backlog in new cars rolling off assembly lines.) Politicians on both the left and right are looking for new ways to boost American capacity in semiconductors, trying to make the country less dependent on a handful of overseas suppliers.

But what I found most interesting in this article was the note at the end, about how a new generation of engineers is working to build a completely new kind of silicon chip technology. “Rather than chop up a 12-in. silicon wafer into hundreds of tiny chips—punching each one out like a gingerbread cookie—Cerebras has found a way to make a single giant chip, like a cookie cake,” Blum reports. That will mean a single, giant chip with trillions of transistors, heralding a new era in supercomputing. “For customers like the drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline and the Argonne National Laboratory, it provides the horsepower needed for breakthroughs in artificial intelligence—a key ambition of U.S. technology policy.” We sometimes forget that computers don’t exist in a cloud, even if our data often does. Rather, they’re made of actual, physical materials. Not every advance in technology will come from programmers and people who work at keyboards. Sometimes it takes a genuine breakthrough in physical engineering to reach the next plane of the digital world. — Eric Johnson

The Beatles/Twitter

Think you know everything there is about The Beatles? Peter Jackson went into the band's appendices—sorry, I mean vaults-to prove you wrong.

The Long and Winding Road *dah-dah* to This Doc

Trigger warning: I’m not much of a Beatles fan. I grew up around their music, but it never resonated. Prince was more my jam. But I still got swept up in the mania around The Beatles Anthology in the mid-‘90s, and I do enjoy the late period albums, Abbey Road and Let It Be, and, like, half of The White Album. What I love unequivocally, though, is movies, and Peter Jackson is one of the most important filmmakers of his generation—even when he’s long in the tooth. (coughcoughTheHobbitTrilogycough) So when it was announced last year that Jackson was digging through the Beatles’ vaults to do something with the footage shot for the long-out-of-circulation Let It Be film, from 1970, my interest was piqued. Let It Be is a decent album (Let It Be… Naked is preferable, if only because it gives us more Billy Preston), and Jackon’s previous non-fiction work, the World War I documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, is a legitimately monumental piece of work. (Jackson took century-old footage, cleaned it up, colorized it, recalibrated the speed to slow it down to the 24 frames per second standard we’re used to, and tastefully dubbed voices over the material to create an eerie and breathtaking portal that transports us back to the Great War.) In the depths of the pandemic, Jackson shared a first look at the Beatles film—which was absolutely joyous, despite the sessions’ reputation as the document of the band’s break up—and it was recently announced the film is now a six-hour miniseries. (Jackson gonna Jackson.)

A feature in the latest issue of Vanity Fair gives us our first real exploration of what The Beatles: Get Back will be, which includes the full 43-minute rooftop concert, the last time the band performed live, and what the remaining Beatles think of the endeavor. It also reorients more than 50 years of Beatles lore: this footage isn’t a dirge, as Beatles fans of long been told, but a celebration, albeit a complicated one. “Mark Lewisohn, the foremost Beatles scholar in the world, spent a month listening to the nearly 98 hours of studio recordings the Beatles made in January 1969,” writes Joe Hagan, “and…was amazed by what he discovered, declaring, ‘It completely transformed my view on what that month had been.’ Far from a period of disintegration, says Jackson, ‘these three weeks are about the most productive and constructive period in the Beatles’ entire career.’” After the year and half we’ve had, we could all use a little transformation and elation. Even if it’s via the Beatles. —Dante A. Ciampaglia