Interview

The Journalist’s Journey

Or, at least, the one that led Dan Kois to a career as a writer, editor, and, now, novelist

Every journalist has a unique origin story. For some, the path to a career as a reporter or editor is a straight shot—they read (or watched) All the President’s Men or grew up with a journo parent or fell in with the school paper and never looked back. But Dan Kois took a twisty-turny route that began in an MFA program, included time working for a literary agent, and a stint with a movie producer. And in a field that has been plagued with massive layoffs and closures exacerbated by the pandemic, Kois has managed to continue creating opportunities for himself.

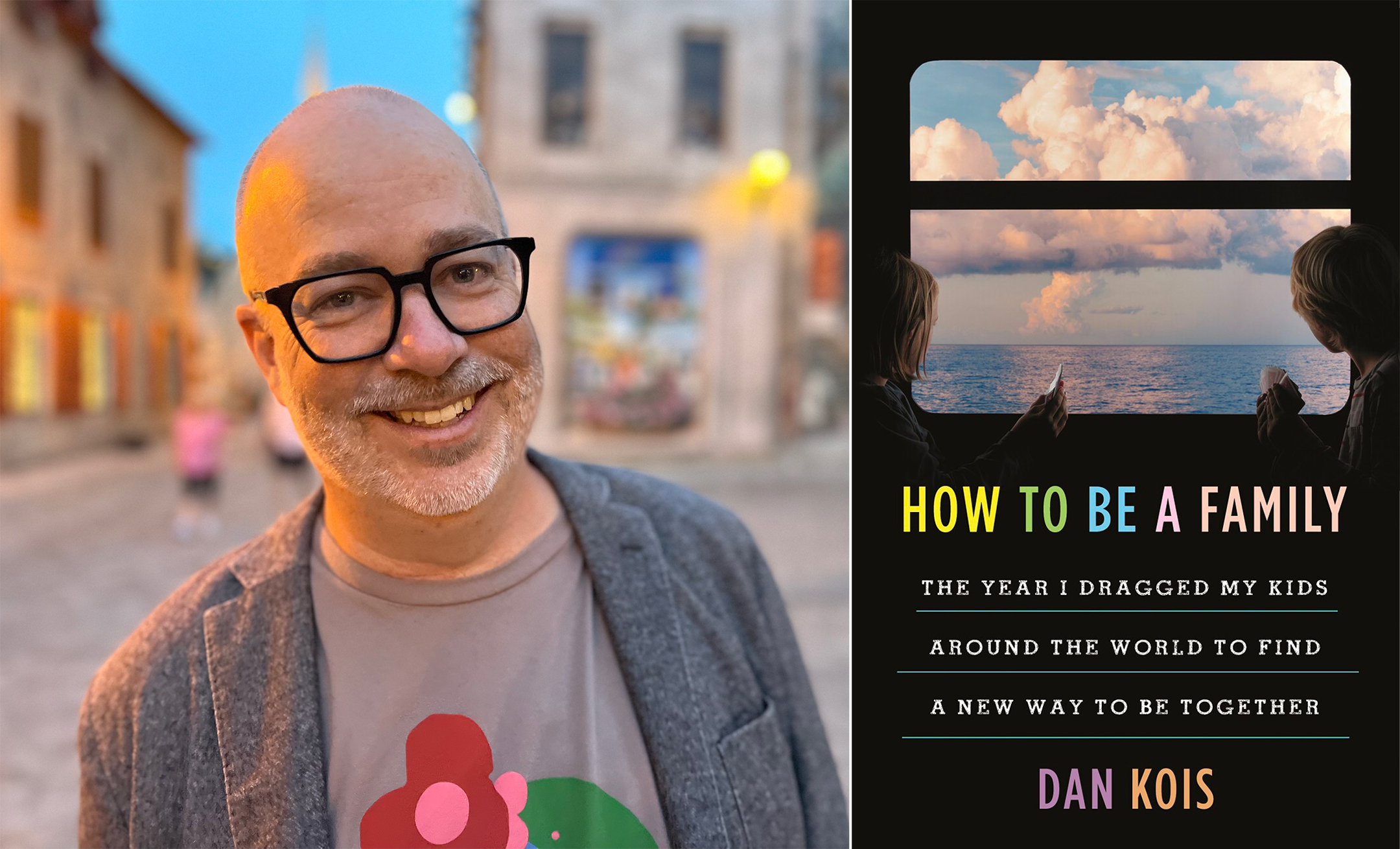

After some time freelancing, Kois became a writer and editor at Slate, contributing articles ranging from “Why Seniors Are Getting So Many More College Rejections This Year” to “The 50 Greatest Fictional Deaths of All Time.” His bestselling travel book-slash-family memoir, How to Be A Family: The Year I Dragged My Kids Around the World to Find a New Way to Be Together, was released in 2019. He cohosts the podcast You Pick Tonight with his daughter Lyra, cohosts another about the author Martin Amis, and has taught writing at two colleges. The next milestone arrives in January with the publication of his first novel, Vintage Contemporaries.

Kois recently spoke to The Elective about his career in journalism, advice for students hoping to enter that tumultuous field, and why he finally decided to write a novel.

Alia Smith (headshot), Little, Brown and Company (cover)

You’ve worn many hats over your professional life. How did you finally decide to focus on journalism?

When I graduated from college, I wanted to work in writing in some way but didn’t have a lot of confidence in myself yet as a writer. Or rather, I had a lot of confidence, but it didn’t mean I was any good at it yet.

While I was getting my master’s degree in fiction at George Mason, I taught at the university to reduce my tuition. I also worked as an assistant for a literary agent in Washington, D.C. who represented a lot of journalists and nonfiction writers. After several years of sort of trying to become an agent, for various convoluted reasons I decided I was terrible at being an agent and didn’t like it. I wanted to write my own stuff.

I had a very, very tenuous connection to Slate. The friend of the wife of a writer for the agency I was at knew an editor there. So I basically cold-pitched myself as a writer. A very nice editor there agreed to meet me, let me come into the office, and I came in with three pages of story ideas. The whole meeting, I just sat and read the ideas out to her one by one. And she took pity on me, assigning me one about iTunes celebrity playlists.

So I just freelanced and freelanced and got various journalism jobs and had an interlude working for a movie producer. But, basically, I just read a lot and wrote a lot. And I spent a long time taking in every single thing I read, every conversation I had, and thinking of it as the nugget for a possible piece, which is the freelancer’s life. Eventually, I was lucky enough to get hired by Slate, 11 years ago, as a staff editor.

How has the uncertainty and changes in the media industry affected your career?

I’ve been very lucky in that I landed at a magazine I really like working for. And while it hasn’t been untouched by the tumult of the last 10 years, it hasn’t had the waves of collapse and rebuild and collapse and rebuild that almost every other digital publication has had. If I worked for The Atlantic or Buzzfeed or someplace else, I definitely would have been laid off by now and then hired somewhere else and then laid off at that place and then maybe hired somewhere else. Who knows, I’m getting old.

There have been a few, very small layoffs at Slate over the last 10 years, but we’ve mostly been able to hold the fort because we’ve had very nice owners who seem to think that there is potential in this industry, despite all evidence to the contrary. It’s been a very bad time to be writing opinions and news for a living. That’s upsetting to me as a reader and as a journalist thinking about my future job prospects. It has definitely made me very appreciative of the place that I landed.

Which is all to say the industry has been a mess, and I have mostly escaped that mess. And I feel very lucky about that.

Given the state of the industry, should a student choose a career in journalism or media today?

Well, it’s not that different from every other industry where everything’s contracting and work sucks and everyone’s going to freelancers. I think that if you are someone who really loves writing and telling stories, and especially if you like the work of reporting, there are still a lot of opportunities out there for you. And other than maybe a 10-year stretch in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when newspapers were flush with classified advertising cash, being a journalist has never been a path to riches. A couple of people become stars, but for the most part it’s hack work in the best sense.

I think if you’re going into journalism as a young person, you are betting on your ability to hustle and put up with a lot of crap. And you’re betting on your own sort of chutzpah. So it tends to attract a certain personality type as a result of that. That kind of person is someone, I think, who would probably excel if they went into a bunch of different industries where there’s been contraction or difficulty.

Gary Scott

Dan Kois and family in New Zealand, one leg of the trip Kois chronicled in his book "How to Be a Family."

You mentioned the need to hustle. How did you convince a publisher that you should travel for a year with your family and write about it for the book that became How to Be a Family?

I often feel a great deal of sadness that I didn’t start my journalism career 10 years earlier, in the era of the legendary Vanity Fair expense accounts, where they just sent Martin Amis to Hollywood for three weeks, and were like, “See if you come back with anything, Martin.” I never had that. But I have managed to find ways to get people to pay for at least a little bit of the interesting things I’ve done. And that seems to me to be one of the great perks of doing personal writing and magazine writing: The rare occasions where you can convince people the crazy idea you have is good enough that they should actually give you money.

In 2016, my wife and I thought what we really needed was a hard reset on our family life, to escape the pressure cooker of Arlington for just a little bit and show our kids everything else that there is in the world. That came out of a trip we took to Iceland in the summer of 2015. I had been really struck by the way that every little town had a beautiful municipal swimming pool, geothermally heated. And because you can’t have a village square, because the entire country’s frozen solid for nine months or a year, these swimming pools become the locus of community.

I pitched this story to the New York Times Magazine. And it was the pitch of my life. I spent weeks writing this thing, honing it, running it by people. I finally sent it in, then spent two months explaining to an editor and her boss why it was a good idea. It finally got green lit, and I went to Iceland for 10 days, swam in 25 different municipal pools, interviewed a million experts and academics and people, and wrote this piece for the Times Magazine.

While I was in edits, I wrote a book proposal that was like this Iceland piece but expanded to include four other countries with my family. What can I learn from each of these different places? Why does family life work in each of these countries, in the Netherlands and New Zealand and Costa Rica and small-town Kansas? The idea of the book would be a mix of the personal and the journalistic. The personal would be our family and what we experienced; the journalistic would be what you, the reader, have often dreamed of doing and how you would do it.

The day the Iceland piece was published, my agent sent this book proposal out to a bunch of publishers along with the piece. I managed to convince one of them that this was a good enough idea for her to throw some money at me, just enough so that we could do the trip and also spend all of our savings and come back only a tiny bit in debt.

After living in four countries, what was the revelation for you about how family life works?

I would say the takeaway is that the place you are living can transform a lot of aspects of your family life. But, also, you and your kids never stop being the people you are and never stop being annoying to each other in the very specific ways you are annoying to each other.

Your first novel, Vintage Contemporaries, will be released in January. After spending so much of your career in magazines and journalism, what finally prompted you to write fiction?

I got my MFA when I was 24, and then I didn't write a single word of fiction for 16 years. When I turned 40 I had a minor midlife crisis, but it was mostly about how I hadn't written any fiction. I was very upset with myself. So I basically started forcing myself every night at 10:45 p.m. to write for 30-to-45 minutes.

I spent five years writing these parallel stories set in 1993 and in the 2000s in New York City. The latter is an era where I did live in New York, and the former is one that I have always heard about, the early ‘90s cultural ferment of the Lower East Side. I didn't know what they had to do with each other, if anything, and I didn't know where they were going. But I was so happy to just be doing something imaginative.

HarperCollins Publishers

It was five years of not knowing what the hell I was doing and then finally figuring out what the thing was. Then it was two years of very, very focused work that included a writer's retreat that I was very lucky to get in Georgia, and some book leave and a lot of opportunities that Slate gave me. But after seven years, I had a book.

Right now, I'm still in the everything-is-great part of this process. It just arrived at my house a week ago; the cover looks great. I'm filled with joy, and eventually I will be filled with despair, I'm sure, as happens with every first novel that has ever been written that is not The Secret History.

You have taught at North Carolina State University and George Mason University. What is the big takeaway you want to impart for students?

I've taught undergraduate and graduate creative writing, and they're very different environments. In undergraduate classes, my goal has always been to expose the students to a wide array of work by writers they maybe wouldn't have otherwise heard of or encountered in their daily reading. It's sort of a literature class in the guise of a workshop. We still look at their stories; I still try to give them the experience of having their stories read by their peers. But I'm mostly trying to get them to read widely and think about what lessons they can pull from that work into their own work.

Graduate classes tend to be a lot more about giving students the experience of being edited—something that, especially in the creative writing field, is very unusual. Until you have reached a certain level of creative writing, where you're getting published in magazines or having a book published, you just don't get your stuff edited that much. I try to give them back their stories, fully marked up in a way that they would see if they’re published in a magazine because that can be really shocking to writers.

What advice would you give to college students who want to become journalists?

You should write for the student newspaper. You should edit at the student newspaper, even if you don't think of yourself as an editor. At most student newspapers, those jobs are there for the taking because they require so much work and effort and no one wants to do them. It is really valuable to see what other people's writing is like, to see the weaknesses and strengths in their work, and to guide them to make that stuff better. And that really helps you get better at what you want to do.

I would also just do a lot of your own writing. Yes, write fiction if you like fiction, or write poetry if you like poetry. But also write as much as you can about your life and your experiences, the people you meet and the things that you do. Even if it doesn't fit in the format of your college newspaper, you'll find that, in the end, it’s a very useful set of skills to develop.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.