Interview

Faith in the Power of Our Differences

Eboo Patel, founder and president of Interfaith America, wants us to stop seeing the nation as a melting pot and more of a potluck

Eboo Patel will be the first to tell you he was a “strident” social activist in his younger says. As a University of Illinois undergrad, Patel says now, he was “so intent on critiquing the system I hadn’t paused along the way to figure out how it actually worked.”

Once he did, Patel saw ways to direct his energy and enthusiasm in directions that can truly affect change, particularly around the nation’s rich religious tapestry. As a Rhodes scholar, he began building the organization that became Interfaith America. The nonprofit’s mission is to “inspire, equip, and connect” leaders and groups “to unlock the potential of America’s religious diversity.” And by working with more than 600 higher education intuitions, it encourages engagement across lines of religious difference on campus, to “leverage the power of interfaith cooperation to build a better world for all.”

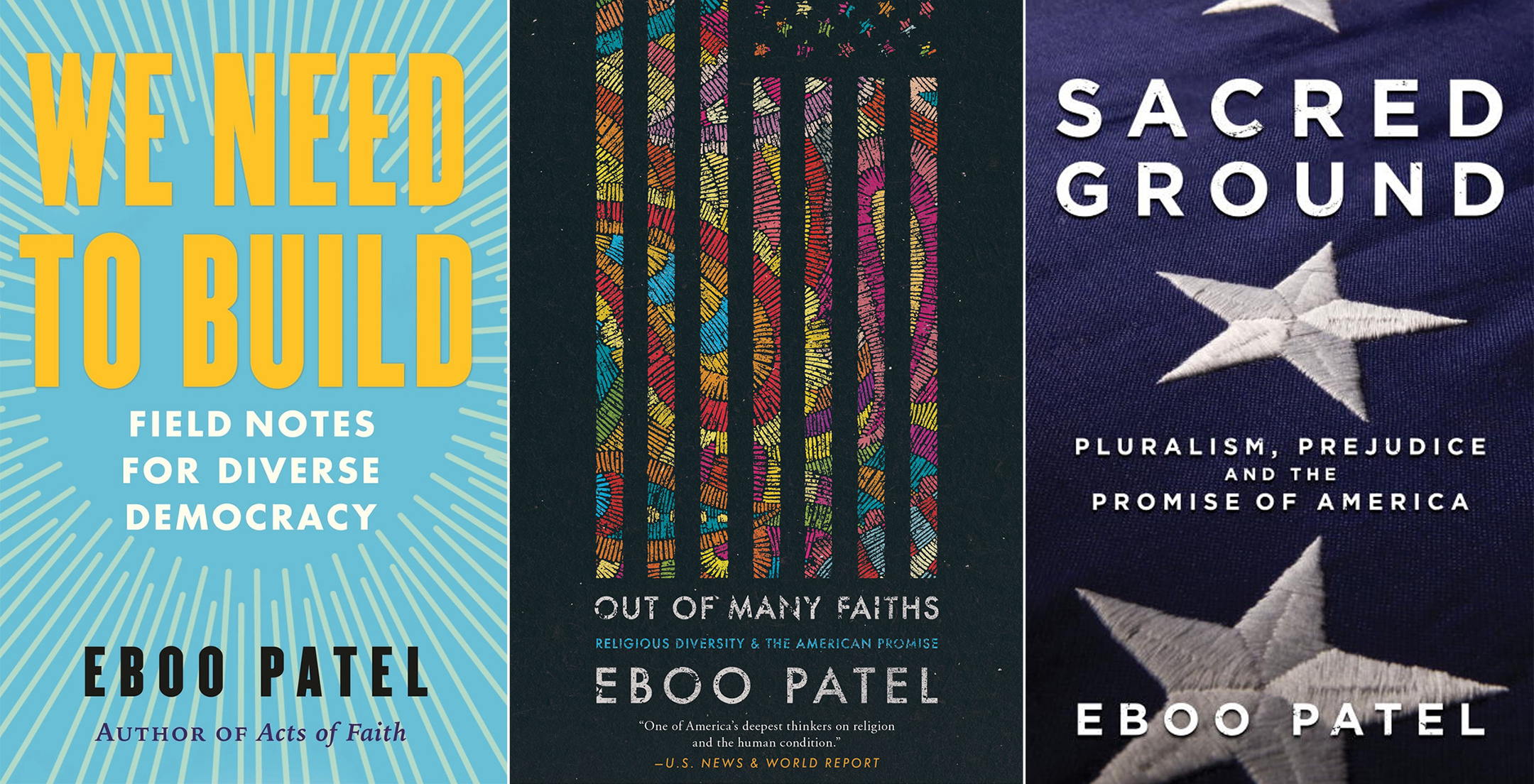

This effort has made Interfaith America—and its founder and president—the nation’s leading voice on interfaith cooperation. Patel served on President Barack Obama’s Advisory Council on Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, has a new podcast, Interfaith America with Eboo Patel, and is the author of five books. The latest, We Need to Build: Field Notes for Diverse Democracy, is a reflection on more than 20 years of institution-building, from those radical-activist younger years to building a disparate collection of small-funded projects into a coherent institution with a clear vision and mission. “The goal is not a more ferocious revolution,” Patel writes. “It is a more beautiful social order.”

Patel recently spoke to The Elective about building new and resilient institutions, the changing landscape of religion in America, and seeing diversity not as a “melting pot” or “battlefield” but as a “potluck.”

Interfaith America

Your organization, Interfaith America, pays attention to that religious diversity and its national implications. You started Interfaith America more than 20 years ago. Where is the organization now, and where do you see it in five, 10 years?

There are a number of great issues in American civic life: racial equity, women's empowerment, environmental stewardship, civil liberties, on and on. Each of those great themes has one or more vital civic institutions dedicated to its advancement: the NAACP, the Sierra Club, and so on. We believe that religious diversity is one of the great civic themes in American life, it deserves a vital civic institution working on it, and we seek to be one of those vital institutions.

There is a great tradition of this in the United States, and in effect we are kind of resurrecting a powerful history that has been forgotten. One of the reasons it's been forgotten is because the vital institution at the center of that history— the National Conference on Christians and Jews—was so successful. It’s now known as the National Conference for Community and Justice, but that institution was responsible for shifting America from its Protestant identity in the early part of the 20th century to a self-understanding of the “Judeo-Christian” nation. That's a really profound shift. And it wasn't based on history or theology. “Judeo-Christian” was neither accurate history nor theology. What it really was was a brilliant civic invention. It was a way of welcoming the civic contributions of Jews and Catholics into the nation at a time of anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism.

So, at a time of new forms of religious diversity, 100 years after the NCCJ was born, we think it's time for the next chapter and the great story of American religion. And we are calling that chapter Interfaith America. And the job of the institution that is Interfaith America is to help the nation that has not yet realized it is “interfaith America” to realize it.

What do you see as the relationship between religion and social change?

A really important thread through the book, and part of my thinking on social change, is that religion is a great model for social change. That’s because the way I understand religions is as an articulation of an ideal and then the building of institutions that manifest that ideal and move us collectively closer to achieving it.

Neither of us are Christians, but let’s use Christian language for a moment. The ideal of Christianity is the kingdom of God, and a church thinks of itself as a physical manifestation and institutional form of the kingdom of God—not just what the church means for its congregants, but for what it does for the diverse neighborhood that it’s in. This is an approach to social change that is, I think, both positive and motivating.

You use the term “Diverse Democracy” in the title of your book. Can you speak a bit on how Interfaith America has approached its work, particularly around diversity?

The last few years in social change and diversity work has been defined by oppositionalism—a resistance, a critique, a dismantling. In social change, it’s how you dismantle stuff; in diversity work, it’s how do you tell the story of your own wounds and wound other people. It’s diversity work as a battlefield.

I want us to think of diversity work as a potluck. Part of what is so wonderful about a potluck is the surprising conversations and the creative combinations that emerge. Someone brings a crusty bread, their grandfather’s recipe from Lebanon. Someone else bring an amazing dip, their uncle’s recipe from Spain. How wonderful is that? When a potluck goes well, it invites the distinctive contributions of diverse people. Your potluck is boring if everyone brings the same thing. And if you want a diversity of dishes, you need to invite a lot of different people. If you have all South Asian Muslims, you might have a lot of biryani. As much as I like it, I don’t want to eat only biryani. If you have a bunch of people from Minnesota, you might have a bunch of casseroles.

(from left) Penguin Random House, Princeton University Press, Beacon Press

You don’t want to erect barriers to people’s contributions. Racism is a barrier to contribution. Anti-Semitism is a barrier to contribution. It’s a violation of people’s dignity, but it also means they can’t bring their delicious dish to the table. It’s just stupid. And it’s hurtful. But notice, I am not using language like “oppressed” and “marginalized.” I don’t expect a barrier to contribution. I don’t assume that this has been internalized, that someone ought to think of themselves as marginalized. Somebody ought to think of themselves as a contributor whose contribution is being hampered by an external force. It’s very different than the assumption of someone internalizing a force like racism.

No one can command someone to have a potluck. It is the ultimate civic form. I think that’s how we should think about diversity work. It’s not a melting pot—we’re not melting identities away. It’s not a battlefield—we’re not counting our own wounds or wounding others. It’s a potluck. We are bringing our own contribution, inviting others’ contributions, and facilitating wonderful conversations and delicious combinations.

We hear a lot about the long-term decline in these institutions, particularly among young people. Often, I'm the youngest person in some of the meetings, and I’m 43. You've worked with young people—what are you hearing from them about the role of religion and religious institutions in their lives?

There's no doubt that there has been a spike in atheists and agnostics, religious “nones” so to speak. For decades the number of people who check the “none” box on religious surveys hovered around 5%, and now it's between 25–30%. And among young people, it’s much, much higher. That's not just a smokescreen, that’s real.

Religiosity really differs by region. So, if you're in Cambridge, Massachusetts, good luck finding somebody who is part of a religious institution. If you're in Mississippi or South Carolina, you might be asked by six or seven people on a Saturday evening where you go to church the next morning; whether you're Jewish or Muslim or not. It’s really regional. I wind up going to Utah a couple of times every year and speaking at one of the universities there. I’m talking about a Muslim going to talk at BYU, Utah Valley, or Utah State University. And the crowds are huge. There are, like, 800 people who show up for stuff.

There is not one story in our country. You go to Portland or Seattle and people are quick to tell you that the Pacific Northwest is the only region in the country where there are more religious nones than religious believers. Well, disaggregate that by race, certainly by immigration status or immigration level if you're first generation, and it starts to look very different. Black people are a lot more religious than white people. First generation immigrants, principally from Africa, South Asia and Latin America, are much more religious. We live in a complicated country.

There’s a 30,000-foot story about religion that misses way too much interesting stuff on the ground. The United States is getting a lot more religiously diverse, and it's not just in New York City or Chicago. There’s a big Hindu temple in Jackson, Mississippi. In Michigan City, a small town right outside of Chicago, there's a Hindu ashram and a Hindu temple. There are as many Muslims in America as Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Lutherans, except the median age of ELCA Lutherans is 57 and the median age of Muslims is, like, 35. These are really interesting data points, and it's going to change the country.

Jason DeCrow-Pool/Getty Images

The Dalai Lama is joined by, from left, moderator Dr. James A. Kowalski, translator Geshe Thupten Jinpa, and panelists Sakena Yacoobi and Dr. Eboo Patel during an interfaith dialogue at the Church of St. John the Divine on May 23, 2010, in New York City.

In 2009, you were named to President Obama's inaugural faith council to build on his pledge to focus on interfaith cooperation. We're more than a decade on from that pledge. Where do you see interfaith cooperation flourishing? Where do you think it still struggles?

There's so much positive progress that is happening at the local level. Six of the nine major refugee resettlement groups were started by religious communities. Lutherans started one, Episcopalians started one, there's HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. They're constantly cooperating with each other to resettle refugees that are not a part of their religious communities. I think that's the most remarkable thing. That's the most American story ever. You should tell that story till the cows come home, right? What we do in America is we are inspired by our particular identity—Jewish, Catholic, Methodist, Muslim, whatever—to build institutions that serve people of all identities.

Another example is hospitals. People are saying their prayers before they go into surgery. And what happens during birth and after death is a bunch of religious stuff. Religion really matters. Different religions have different definitions of the moment of death. And so if you’re a physician, you're oftentimes in the middle of a conversation between say, Evangelical and atheist halves of a family on when grandma should be declared deceased. These are deeply religious spaces and deeply interfaith spaces in which most things go right. Most of the time. I think that's really beautiful. And we ought to remember it.

At the end of your book, there’s a really moving letter that you write to your sons. You talk about your childhood, the racism that you experienced, and the defensive way it made you act out against others. You recall a Buddhist saying that getting angry is “like drinking poison and hoping your enemy will die,” which I found super resonant and honestly helpful in my own life. There is obviously for your own sons a lesson that there is a place where anger is useful and but it can then tip into being destructive.

Yes, but it's also important to “rightsize” it. What I mean by that is the racism I experienced was ugly, but not debilitating. And I do not want this to blind me from all of the massive privileges in my life, many of which were very tangible. I went to an excellent public school. I grew up in a country in which you can breathe the air and drink the water—you can’t in a lot of places, and I am from one of those places. So I think it's important to kind of rightsize things. That doesn't mean you paper over the bad stuff. It just means you rightsize it in your own psychology.

I think that a big part of the problem of anger, resistance, critique, and rage is the way it messes with your psychology. That’s what it does to you. It's like taking poison and poisoning yourself. And it turns many people off, and it doesn’t create things that are better in the long term.

I’m not saying all righteous anger is bad. There are times in my life when I wish I had thought before I’d raged an awful lot, and I know an awful lot of people now who wish they had thought before they’d raged. But I really do think that long term, strategic institution building is what makes the difference in people’s lives. As I put it in the book, the goal of social change is not a more ferocious revolution, it’s a more beautiful social order.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.