News

Nudges, Not Sales Pitches

Unexpected text messages are often dismissed as spam, but new research shows how to reach students in ways that help, not hinder, applying to college

You need to reach people where they are—any good marketer will tell you that. And when it comes to teens, the conversation begins and ends with their phones. A 2018 Pew Research Center report found that 95% of American teenagers have access to a smartphone, and almost all of them use it to connect with people. They rarely use email, and don’t even try to call. But texting is still a thing, which is why nonprofits and researchers have tried text-based campaigns, called nudges, to encourage high schoolers to pursue college.

It sounds like a good idea. It’s widely believed many high school students lack access to a well-trained school counselor. Without adequate information some low-income and underrepresented students never enroll in college, while others enroll in less-selective universities, although possibly qualifying for more resource-rich institutions. Despite some early promise, though, the text-nudge experiment hasn’t gone well.

“Digital Messaging To Improve College Enrollment And Success” (DIMES), shared by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in October, adds to accumulating research showing large-scale automated texting campaigns do not solve the problem of inadequate college counseling. But the NBER paper does make a valuable contribution to what we can learn from these failures.

“Who the messenger is really, really matters,” University of Pittsburgh professor Lindsay Page, one of the coauthors of the study, tells The Elective. Once upon a time, texting felt like “a protected and personal channel of communication,” Page adds. But with marketers, politicians, and scammers acquiring people’s numbers, it’s increasingly common to treat texts as spam.

chee gin tan/Getty Images

Supporting students through text messaging as they move from high school to college sounds like a good idea. But researchers studying these text nudges have seen their campaigns result in lackluster outcomes.

That’s reflected in the data. In 2012, Page and University of Virginia professor Ben Castleman collaborated with uAspire to create “an automated and personalized text messaging campaign to remind college-intending students” to complete required tasks to complete their matriculation. Texting helped reduce “summer melt” —when students enrolled in college simply never show up—by 4 to 7 percentage points. A 2013 texting campaign reminding college freshmen to complete the FAFSA showed similarly promising results.

But the excitement around those early successes was tempered when researchers applied the strategy at a much larger scale. One study, published in August 2019, sent more than 800,000 high school seniors text reminders to apply for financial aid between 2015 and 2017. It showed “no impacts on financial aid receipt or college enrollment overall or for any student subgroups.” Another campaign, spanning the same time frame, sent informational mailers to 785,000 low- and middle-income students with strong qualifications and supplemented the mailers with text messages. The researchers found “no changes in college enrollment patterns.” (One exception was a small increase in the selectivity of colleges attended by African American and Hispanic students.)

Text nudges failed to help get students into college and did little for students who did enroll. A five-year program that sent nearly 25,000 students study reminders found the messages not only failed to help students but might have actually led to worse grades. Casting subtlety aside, the researchers titled the paper “The Remarkable Unresponsiveness of College Students to Nudging And What We Can Learn from It.”

SDI Productions/Getty Images

Despite some promising early results, when researchers applied text nudges at a larger scale they found little success in impacting financial aid or college enrollment outcomes for any student subgroups.

Knowing these outcomes, the team behind the DIMES paper ran two projects to identify what works and doesn’t in nudging students. The first was a nationwide campaign launched in collaboration with the College Board and uAspire that supported students in the college application and enrollment process. The other was done on the state level and included participation from school counselors.

In the national campaign, uAspire contacted more than 70,000 students in more than 700 high schools once a month, encouraging them to respond to receive college advising via text message. For the state-level experiment, conducted with 72 high schools in Texas, texts were more frequent and more personal, coming every one to two weeks from a counselor in the students' own schools.

The difference in outcomes was stark. Only 3% of students in the national study participated at a high level, defined as responding an average of seven times to new texts. More than a third of the participants never responded. In Texas, students engaged at a lower rate with the messages but they could follow up with their counselors in school and in email, which many of the texts encouraged them to do.

The key difference between the two campaigns was that the one in Texas led to positive results across the board, including taking the SAT®, completing the FAFSA, and applying to and attending an in-state public university. The national campaign, meanwhile, showed “little evidence that student outcomes were improved by the outreach.” Worse, those students were slightly less likely to enroll in college. The nudges had “modest negative and a statistically significant effect of just over one percentage point in on-time college enrollment.”

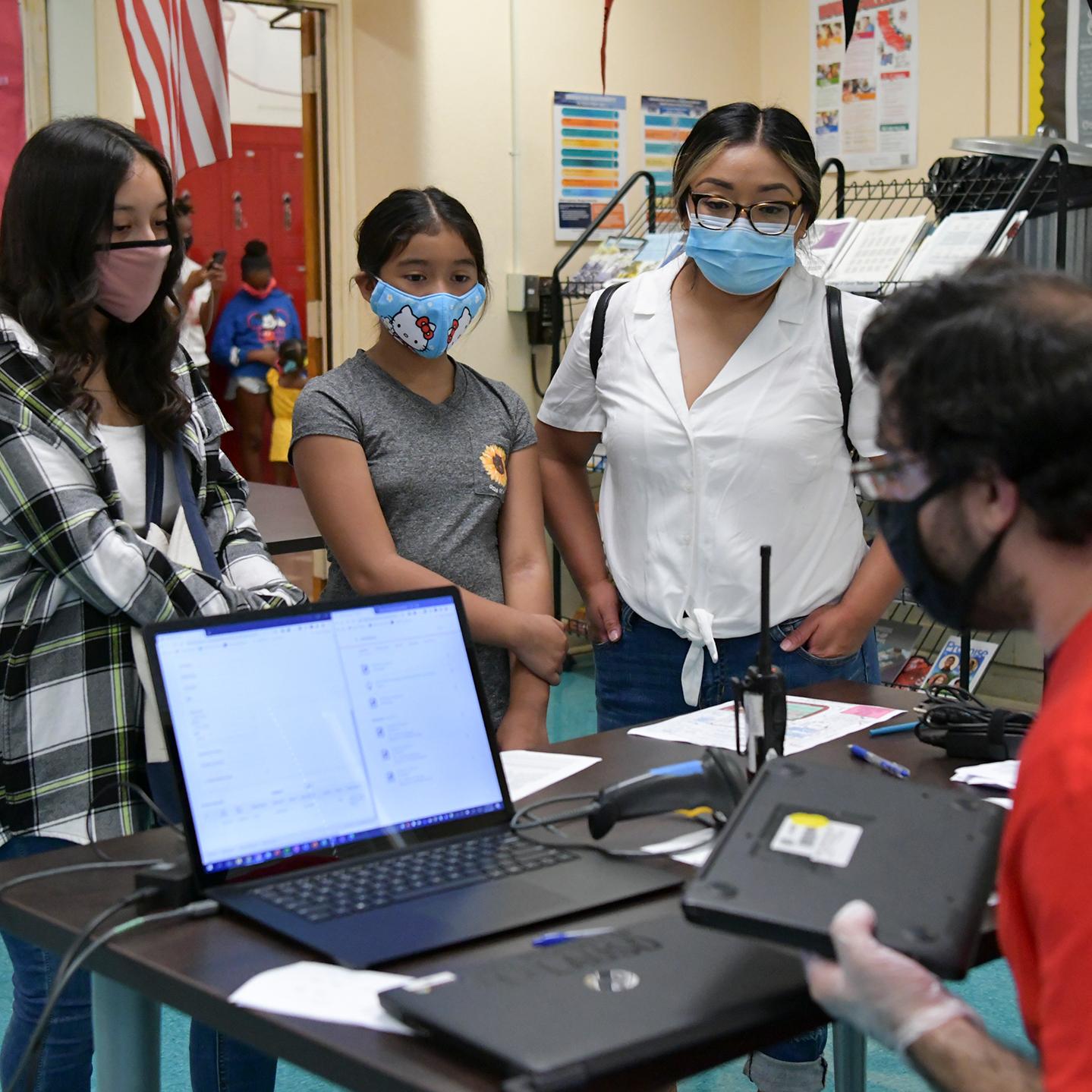

eyecrave/Getty Images

More localized texts, sent to students from counselors they know and see at school, have been shown to be more impactful than other, more national nudge campaigns. "Who the messenger is really, really matter," says professor Lindsay Page.

The authors of the study speculate several factors may have contributed to the difference in outcomes. But the main factor appears to be context.

The negative effects seen in the national campaign could have resulted from advice uAspire gives about the benefits and costs of attending college, leading some students to avoid risky colleges they might otherwise have attended. In Texas, though, the messaging was local, allowing for coordination with in-school activities and personalization based on students’ progress in the application process.

Perhaps more importantly, the personal connection between a student and a counselor likely created a greater sense of trust and responsibility. If a text comes from an organization you have no connection to other than as a customer, it can look like spam. But it’s harder to ignore when you’ll probably see the sender at school the next day.

Page suggests that future campaigns should build on personal connections by “equipping school counselors and other organizations with the tools to do this kind of outreach” while cutting back on repetitive tasks, like sending out endless emails. A counselor will likely get a much better response from an automated reminder to complete the FAFSA sent in her name than if it comes from an agency or company. And automating some tasks will give counselors more time to focus on the invaluable, one-on-one advising that should be their primary responsibility.

Nudging isn’t meant to fill in for counseling, nor can it—students need humans they know and trust, not corporate bots, to help them navigate admissions. But technology can make the college application process better by enhancing, not replacing, human relationships.